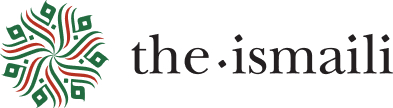

A great debate takes place between the animals and the humans at the court of the king of the jinn. Through this story, the 10th century thinkers known as the Ikhwan al-Safa raised interesting questions on the nature of humanity and how humans differ from animals. Copyright: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

A great debate takes place between the animals and the humans at the court of the king of the jinn. Through this story, the 10th century thinkers known as the Ikhwan al-Safa raised interesting questions on the nature of humanity and how humans differ from animals. Copyright: The Institute of Ismaili StudiesSonia Dhanani, a fourth-grade religious education teacher in Long Island, smiles as one of her students starts debating another, who is dressed in a tiger costume.

They are enacting an adaptation of the Case of the Animals versus Man from the Rasa'il Ikhwan al-Safa – narrated in the Primary Four Ta‘lim curriculum materials – and some of the students are getting a little too passionate about their roles. As Dhanani reads aloud the story about a struggle between the humans and the animals, the students take on different roles using the animal masks that they have made in class.

Once the excitement of the play is over, Dhanani settles the children into a circle where they discuss what they learnt.

One girl says that the story reminds her of another that they read the previous week about Kalila and Dimna. In that fable, based on a Persian translation of the Indian Panchatantra, two beasts learn about right and wrong, and how humans have the ability to choose between them because they have the gift of intellect.

“That's right,” says Dhanani. “We all have Kalila and Dimna inside us and we can always choose which one we want to be.”

As the class carries on, the children learn about spirituality through devotional poetry, read about ethics, and take part in a newscast skit to review the lessons of the day.

Multifaceted approach to religious education

Since 1990, the international Ta‘lim curriculum has embraced a wide range of subjects in religious education, approaching Islam from the perspective of beliefs, practices, ethics, culture, art and literature. This content is presented through activity-based lessons, group work and enquiry-centred learning, all of which have become integral in the education of primary students.

But to be successful, the Ta‘lim approach required changes in the way religious education teachers were trained.

“We had Dar al-Tarbiyyah al-Islamiya training, which was a way to teach the teachers what they would have to teach the kids,” explains Salmin Pardhan, Executive Officer of the Ismaili Tariqah and Religious Education Board (ITREB) for the USA. While this programme sought to address ways in which content, pedagogy and classroom management could be integrated, teachers would need to be conversant with the educational philosophy and content of the Ta‘lim curriculum, and have the pedagogical skills necessary to teach primary level children.

This gave way to the Primary Teacher Education Programme (PTEP), which places equal emphasis on both what to teach and how to teach it. PTEP seeks to develop a pool of teacher educators who can train primary level religious education teachers to impart their knowledge effectively. ITREBs harness the skills of qualified professional teachers to act as teacher educators, enabling volunteer teachers to benefit from the specialist knowledge and experience of professional practitioners.

In keeping with the philosophy of the Ta‘lim curriculum, PTEP is based on an interdisciplinary approach to Islam, approached from both a faith and civilisational perspective. Centred on the Shia Ismaili understanding of Islam, it aims to guide students to acquire a better sense of their identity as Ismailis while also being respectful of other traditions. Within this framework, teachers are acquainted with educational approaches that are suited to teaching religious education to young children.

In Primary Two, Hoopoe, the bird of wisdom, takes children on a journey into the past. Here Hoopoe introduces the Fatimid city of Cairo. Copyright: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

In Primary Two, Hoopoe, the bird of wisdom, takes children on a journey into the past. Here Hoopoe introduces the Fatimid city of Cairo. Copyright: The Institute of Ismaili StudiesCatering to the ways in which children learn

The approach takes into account how children learn concepts, skills and values. It recognises that different children require different strategies to make learning effective for them.

“It asks the question, ‘How do I cater to the needs of all my students?'” says Nish Thaver, the National PTE Team Lead in Canada. “You have to look at it through the students' lens. Are they visual learners, artistic learners, or musical learners? There is less of a lecture, and more media through which the lessons are taught.”

Activities are hands-on, and include reading articles, reciting and understanding verses of the Qur'an, listening to ginans and qasidas, and performing skits depicting historical events. Most lesson plans use two or more techniques, thereby appealing to a majority of students.

One of the aims of Ta‘lim is to make Ismaili children aware of the pluralistic world in which they live, and to develop respect, tolerance and understanding towards people of other faiths. The study of Muslim history and civilisations in the curriculum reinforces this.

“The sixth grade curriculum is a great example,” explains Faridah Merchant, a Teacher Educator from Edison, New Jersey. “It describes religion within its cultural context, and includes art, literature, music, society, governance and other factors that make a civilisation distinct. This evolution [of Muslim societies] tells the students that Islam is not a monolithic faith.”

History records the development of a rich diversity of Muslim traditions, each with its own understanding of Islam. In making students aware of this pluralism within the ummah – both in the past and the present – they recognise what they hold in common with other Muslims, and what is distinctive to their own Shia Ismaili tradition.

Reaching out to parents through their kids

Primary Four students explore the rich literary history of Muslim stories through adaptations of stories like Farid al-Din Attar's The Conference of the Birds, depicted here. Copyright: The Institute of Ismaili Studies

Primary Four students explore the rich literary history of Muslim stories through adaptations of stories like Farid al-Din Attar's The Conference of the Birds, depicted here. Copyright: The Institute of Ismaili StudiesGiven these aims of the curriculum and the teacher training programmes, a concerted effort is made by the ITREBs to ensure that they reach out to as many parents and children as possible.

“We'd like to be able to pull the kids into the RECs (Religious Education Centers) rather than push them in,” says Pardhan. “Kids now have many commitments, with school, sports and extracurricular activities. REC should be a top priority as well.”

Children are not the only end recipients of the programme. School administrators are trying to get more young professionals – particularly parents – involved as well.

“We've seen that younger people already relate well to the curriculum since many of them have gone through it,” explains Thaver. “They can have a better connection with the children they are teaching, and they tend to have good relationships with the Jamat.”

Farzana Noorani, the parent of a fourth-grade student in Texas, appreciates the fact that there has been greater effort on the part of teachers and administrators to keep parents informed about classes. “Administrators have been calling parents to inform them about special events, parent-child journals, and what's happening inside the classroom,” she says.

Doing so fulfills one of the objectives of Ta‘lim – to share the teaching and learning on a wider scale with the community, especially with parents. Thaver points out, there should be a clear connection between what happens at Bait-ul Ilm for three hours each Saturday, and what happens at home.