Fifteen years ago, the Aga Khan University crossed the Indian Ocean. At the invitation of the governments of Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda, AKU set up an Advanced Nursing Programme in each country — the university’s first academic initiative in Africa.

At the same time, the three countries were up to something remarkable of their own. They had recently concluded a treaty — which came into effect in July 2000 — that brought into existence a regional intergovernmental organisation known as the East African Community. Their motto: One People. One Destiny.

In 2007, EAC membership expanded to five countries with the addition of Rwanda and Burundi. The university was about to expand as well. It revealed plans that same year to build a major new campus in Arusha — coincidentally, the city where the EAC is headquartered.

“This project is, I believe, the first major private sector investment in the East African Community since the formal joining of Rwanda and Burundi,” said Mawlana Hazar Imam as he announced the new campus at a state banquet in Dar es Salaam that August. “It is the biggest expansion step for the Aga Khan University since it opened in Pakistan almost 25 years ago.”

Moving forward together

The East African Community is young but ambitious. Its treaty calls for a customs union, a common market, and a monetary union, with the eventual goal of political federation. Realising all this will require vision, goodwill, political cooperation, and access to a deep pool of educated leaders.

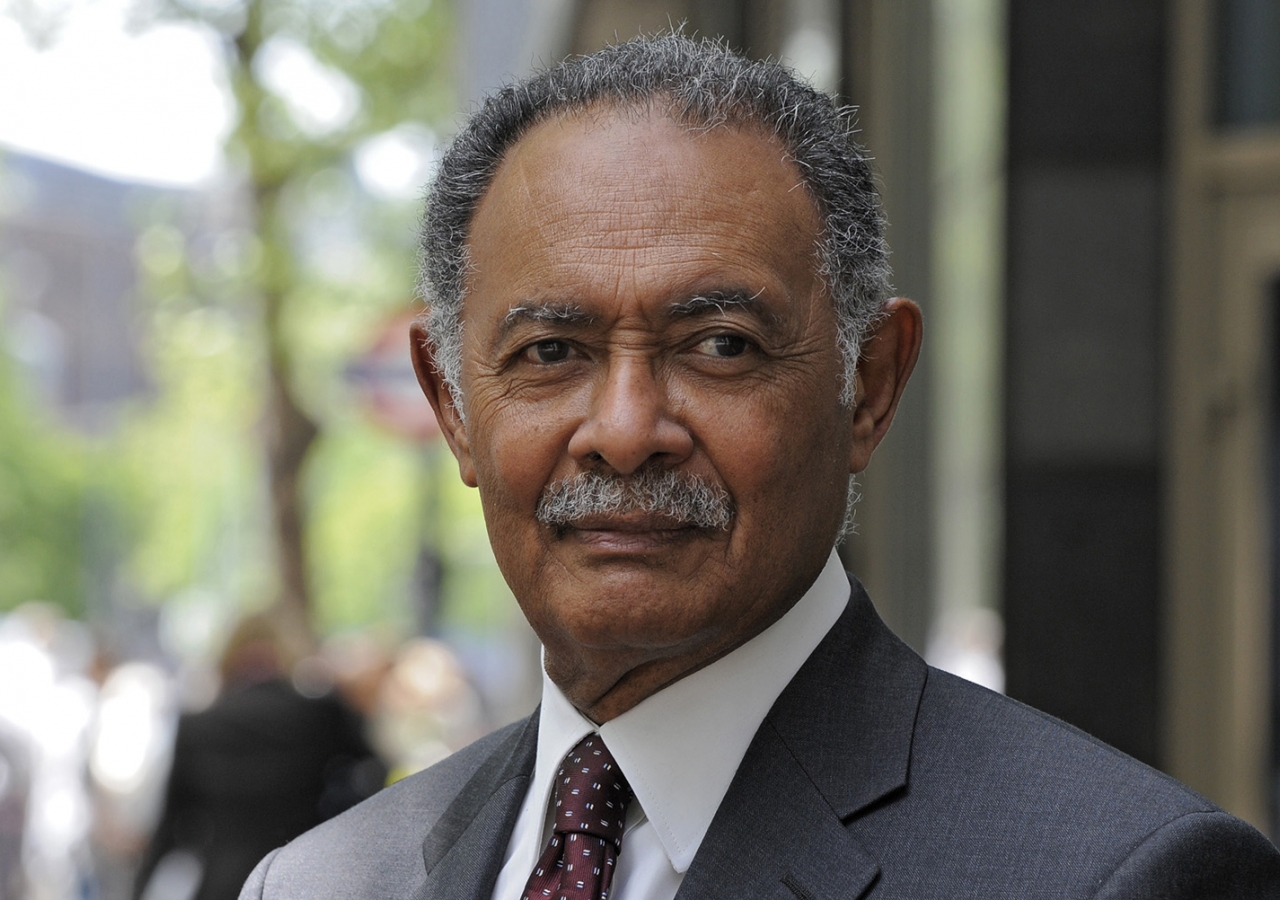

“We are just at the very beginning of our journey,” says Dr Farouk Topan, a scholar at the Aga Khan University. The grandson of Varas Sir Tharia Topan, he was born in Zanzibar and pioneered the study and teaching of Swahili Literature in Kiswahili at the University of Dar es Salaam and the University of Nairobi in the 1960s and 70s. Dr Topan received his PhD from the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, where he later held the position of Senior Lecturer, having also been with The Institute of Ismaili Studies.

Now attached to AKU’s Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilisations and the nascent Faculty of Arts and Sciences in Arusha, he maintains a close connection with the East African region.

“I think the Faculty of Arts and Sciences is a tremendous step forward as the aim is to educate the youth in the round,” says Dr Topan. “The curriculum has been thought through with the aim of providing skills of leadership as well as a broader sense of grounding and vision.”

The ideal, he says, is to produce “East Africans who take each other as what they are — human beings living in one place, facing common problems and who are moving forward together.”

Informing policy

To assist in addressing their shared problems, AKU launched the East African Institute in 2014, a policy and research platform that focuses on addressing regional challenges that confront East Africa.

“The EAI is a think tank, which is partly informed by the activities of the EAC,” says Dr Topan. Its function in turn, is to apply research and analysis “to inform the policy makers” and help them address challenges that confront East Africa. By virtue of the university’s affiliation with the Aga Khan Development Network, the EAI is positioned to turn its research into practice, enhancing its impact.

Food security is one of the issues that the Institute is already looking at. “I think that is absolutely crucial,” says Dr Topan. “On the one hand you have malnutrition and on the other you have poor management of the ecosystem,” he explains, “and then when you have famine — this just compounds the problem.”

Another area is education policy “as a tool for unifying people,” says Dr Topan. “But here it is to do with parity of education, so that there is regional integration through education.”

“You achieve that through the curriculum on one hand, but also through vision — and that vision needs to be shared by the leaders of the countries,” he says.

Common language

Language is another important tool for bringing people together. While English is the official language of the East African Community, the EAC is developing Kiswahili as its lingua franca.

Colonial languages, like English and French, or traditional languages could dominate certain regions and possibly be divisive, but Kiswahili has the potential to unify. The language is already spoken throughout the region “in varying degrees,” says Dr Topan and it can enable trade, for example, functioning as a bridge in the EAC’s common market.

It is not surprising then that AKU recently launched a Kiswahili Centre, with Dr Topan as its director.

Part of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, the initial focus of the Centre is on developing the first digitized collection of Kiswahili literature in the world, bringing together materials on the heritage of the Swahili language and people from at least as early as the 17th century, including their history, literature and music.

“It is quite unique in East Africa to have a literature that goes back centuries”, says Dr Topan. Translated where appropriate, the collection will be a means to both preserve Swahili texts and make them available to a worldwide audience.

The collections and work of the Centre will help contribute to courses in the core curriculum of the undergraduate liberal arts programme. The Centre will also host lectures and conferences on issues that are important to the region.

Seeds of optimism

The university’s plans for the next 15 years are extensive. Investments in health sciences will strengthen healthcare in the region and expand the number of health professionals trained in East Africa. The recently launched Institute for Human Development focuses on early child development. A future Entrepreneurship and Innovation Centre will offer programmes in social and business entrepreneurship, with a special focus on women’s entrepreneurship. And a new Programme on Social Change will encourage the examination of questions in the context of East Africa.

“I think the future is bright,” says Dr Topan thoughtfully. “We can dream, because Hazar Imam has already put the beginnings in place — so we are not dreaming aimlessly.”

“The seeds are there for people to feel optimistic.”