A sunset view of the Aga Khan University campus in Karachi. When it opened in 1980, the AKU School of Nursing was the first to be affiliated with a university. It has significantly raised the quality and standing of nursing in Pakistan, restoring dignity and honour to the women who serve in this profession. AKDN / Jean-Luc Ray

A sunset view of the Aga Khan University campus in Karachi. When it opened in 1980, the AKU School of Nursing was the first to be affiliated with a university. It has significantly raised the quality and standing of nursing in Pakistan, restoring dignity and honour to the women who serve in this profession. AKDN / Jean-Luc RayArchitecture, explains Farouk Noormohamed, is about more than designing a structure to serve a function.

“Every building has an influence on people,” he says. “How we actually craft that building is going to influence the lives of people.” Good buildings, he continues, “seek to improve the quality of interactions of the people served by them. They are a representation of not only the current state of a society, but of its future.”

An award-winning architect, Noormohamed is also a Fellow of the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada (RAIC), which “seeks to build an awareness and appreciation of the contribution that architecture makes to the wellbeing of Canadians,” he says.

Today the Architectural Institute is recognising Mawlana Hazar Imam's contributions to architecture by awarding him their Gold Medal.

Mawlana Hazar Imam and Prince Amyn take in a view of the mountainous Hunza valley from the vantage point of the 700-year-old Baltit Fort, whose restoration by the Historic Cities Programme of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture began in 1992. AKDN / Gary Otte

Mawlana Hazar Imam and Prince Amyn take in a view of the mountainous Hunza valley from the vantage point of the 700-year-old Baltit Fort, whose restoration by the Historic Cities Programme of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture began in 1992. AKDN / Gary Otte“The Gold Medal is the highest honour that [the Institute] can bestow in recognition of a significant and lasting contribution to Canadian architecture,” says Diarmuid Nash, a past president of RAIC and partner at Moriyama & Teshima Architects in Toronto. “I am delighted that it is being awarded to His Highness the Aga Khan,” he adds.

Nash and his firm have been integral to several of Mawlana Hazar Imam's architectural undertakings in Canada, working closely with Japanese architect Fumihiko Maki on the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat situated along Sussex Drive in Ottawa and the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto, as well as with Mumbai-based architect Charles Correa on the Ismaili Centre, Toronto. These projects illustrate a larger vision of architecture that serves the public by educating, encouraging constructive exchange and fulfilling a social responsibility that is central to the Muslim faith. Additionally, these spaces resonate with the pluralist values of Canada.

According to Nash, the many initiatives established by Mawlana Hazar Imam around the world “such as the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the Historic Cities Programme and the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, inspire, inform, and provide direction, but ultimately lift the bar for all of us in the design community.”

And this is precisely the objective, says Farrokh Derakhshani, Director of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. “I believe that His Highness' major contribution to international architectural discourse has been his emphasis on architecture as a service to its community,” he says. “In fact, the notion of sustainability in architecture – now in vogue – is something the Award has been talking about since its inception some four decades ago.”

“His Highness' stress on the importance of buildings that have a positive impact on the lives of people – rather than those that function simply as aesthetic statements – resonates widely,” points out Derakhshani. “This was not always the case.”

It is hard to believe that the 74-acre Al-Azhar Park was a garbage dump for over 500 years. In addition to transforming it into a beautiful green space that showcases some of the oldest monuments of Islamic Cairo, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture Historic Cities Programme has leveraged it to rehabilitate surrounding neighbourhoods, and to provide economic and social benefits to the communities that live there. AKDN / Gary Otte

It is hard to believe that the 74-acre Al-Azhar Park was a garbage dump for over 500 years. In addition to transforming it into a beautiful green space that showcases some of the oldest monuments of Islamic Cairo, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture Historic Cities Programme has leveraged it to rehabilitate surrounding neighbourhoods, and to provide economic and social benefits to the communities that live there. AKDN / Gary OtteNor was it obvious to many that there could be a strong link between valuing cultural assets and sustainable development. A recurring phenomenon in many parts of the world is that where you have historic buildings and monuments in states of degradation and disrepair, you often find marginalised communities living in the vicinity. Mawlana Hazar Imam recognised that, if managed with care, this situation could be turned on its head – rather than being seen as liabilities, historic cultural assets could become catalysts in lifting communities out of poverty.

The success of this idea is embodied in the Historic Cities Programme of the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, which demonstrates how the intelligent restoration of cultural heritage and urban regeneration can result in a sustained improvement in the quality of life of communities. One example is the creation of Al-Azhar Park and the restoration of surrounding monuments in Cairo, which has resulted in new employment opportunities and the rediscovery of lost skills and trades among people living in the adjacent Darb Al-Ahmar district, as well as improvements in the quality of housing, infrastructure, social programmes and the strengthening of civil society.

Having worked closely with Mawlana Hazar Imam on projects such as the Aga Khan Academy in Mombasa, Kenya and the Ismaili Centre, Dushanbe in Tajikistan, Noormohamed says that the experience has had a profound influence on his overall professional practice, pushing him to ask larger questions and to experiment with new ideas. “My experience with these projects is deeply ingrained in the way I think about architecture, and the architecture that comes out has a deeply human quality to it.

Noormohamed believes that the impact of the architecture and ideas of the Muslim world on western societies is only starting to be felt. “When you have a building like a museum, it talks about architecture in a larger context. People visit museums and begin to understand.”

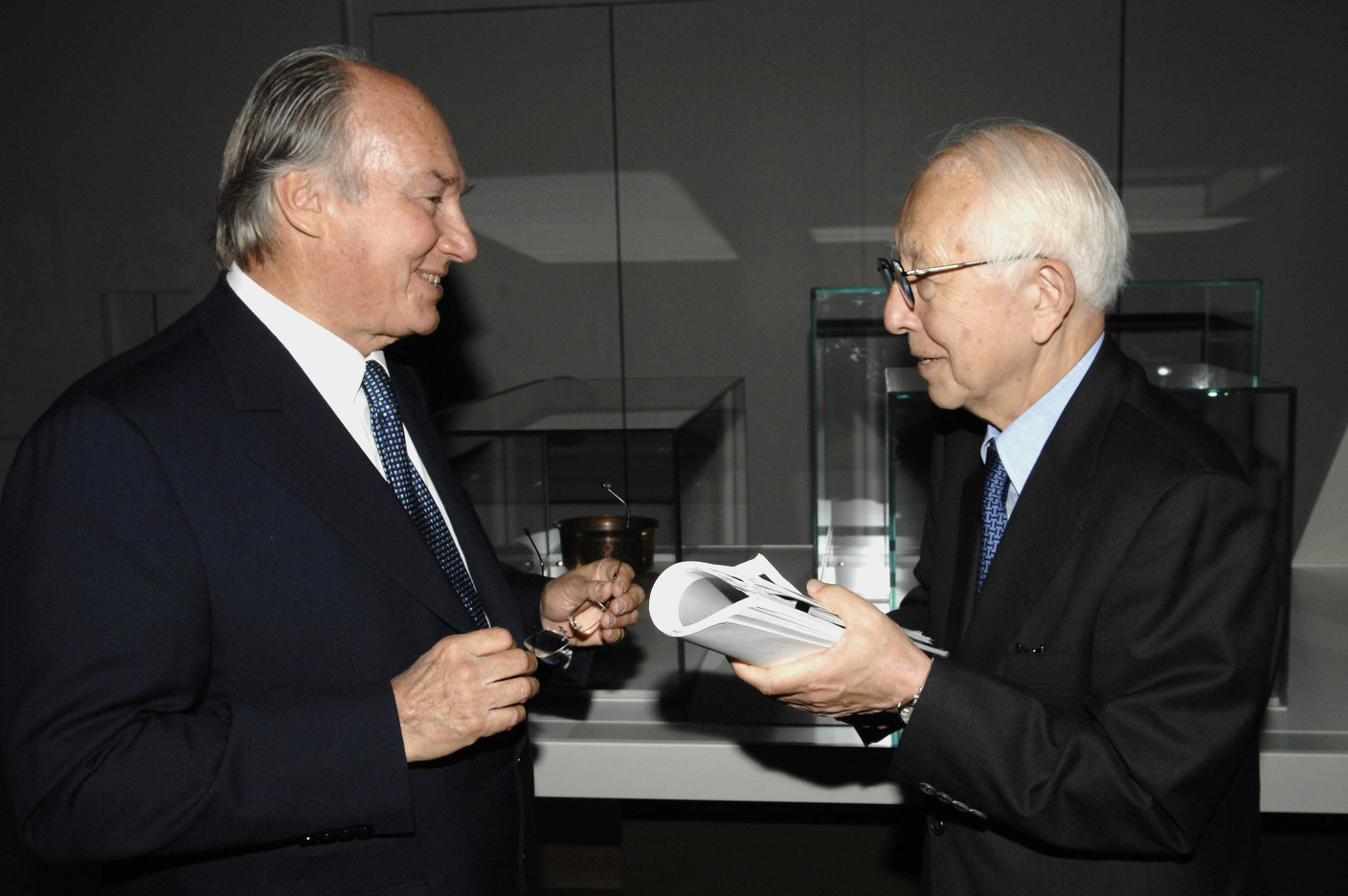

Mawlana Hazar Imam with architect Fumihiko Maki at an Aga Khan Museum Exhibition held at the Louvre in 2007. The renowned Japanese architect has served twice on the Master Jury of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, and designed both the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto and the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat in Ottawa. AKDN / Gary Otte

Mawlana Hazar Imam with architect Fumihiko Maki at an Aga Khan Museum Exhibition held at the Louvre in 2007. The renowned Japanese architect has served twice on the Master Jury of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, and designed both the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto and the Delegation of the Ismaili Imamat in Ottawa. AKDN / Gary OtteRAIC's awarding of the Gold Medal to Mawlana Hazar Imam makes him one of few non-architects to be awarded the Medal – joining the Right Honourable Vincent Massey, the former Governor General of Canada who established the Governor General's Medals in Architecture, as well as the celebrated author and urban thinker Jane Jacobs. With this distinction, the organisation is recognising the Imam's “extraordinary achievements using architecture as an instrument to further peaceful and sustainable community development around the world.”

In particular, RAIC cites the impact of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. Established in 1977 and presented in three year cycles, the Award seeks out projects that set new standards of excellence in shaping the built environment. There is no typical winner; recipients have included contemporary buildings such as the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur, the rehabilitation of Hebron Old Town in Palestine, post-tsunami housing in Sri Lanka, and an Islamic cemetery in Altach, Austria. What the winners do share is that they address the needs and aspirations of the peoples that they serve in a manner that is sensitive to their cultural expectations and reflective of societal values.

Derakhshani notes that “during the past Award cycles, many prominent architects have made intellectual contributions to the Award. Although it is difficult to point out the direct impact of the Award on Canadian projects, one can imagine that the Award's philosophy and approach are now shared by many kindred spirits in the country.”

Moriyama & Teshima attests to this firsthand. They worked on the restoration and development of the Wadi Hanifa wetlands near Riyadh – a project that received the Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2010. “The Aga Khan Award for Architecture has opened eyes and minds,” says Nash, “by recognising and elevating extraordinary design work that has contributed in a significant way to its community.”

“Is it possible to measure the collective impact of His Highness' endeavours on the practice of architecture globally?” ponders Nash. “I don't think there is a measuring stick long enough that would encompass the global impact of the work of the Aga Khan in new schools, universities, hospitals, cultural facilities, historic gardens and building restoration, each project enriching lives and creating economic growth.”

“There is such a strong relationship between His Highness and excellence in architecture; they are in a way synonymous.”