It is believed to be one of the fastest growing forms of organised crime in the world, though most people ignore it or are simply unaware. But through a five-part series currently being aired on BBC World Television, executive producer Faridoun Hemani and researcher Jazzmin Jiwa hope to change that. They assert that human trafficking is “a modern form of slavery.”

“Human Trafficking is an invisible crime, yet it touches us every day,” says Hemani, a former war correspondent who has worked with major news broadcasters like CNN and ABC News. In 1997 he formed Linx Productions, an independent producer of TV news and documentaries. “Trafficked people could be cleaning our homes and offices, making the clothes we buy, growing the food we eat – we are totally unaware.”

Hemani's position is echoed by international organisations seeking to raise awareness and fight human trafficking. “Slavery is a booming international trade, less obvious than 200 years ago for sure, but all around us,” said Antonio Maria Costa, Executive Director of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime, at the launch of the UN Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking (UN.GIFT) in March 2007.

The United Nations estimates that human trafficking and related activities like forced labour produce annual profits of $32 billion, second only to illegal arms sales, and ahead of the illicit drug trade. Studies show there are approximately 27 million “slaves” in the world today, most of whom are women and children, with forced labourers representing a significant proportion of that number.

Creating awareness

Hemani and his company first got involved with the issue two years ago, when they were hired to run an awareness campaign that included the production of public service announcements (PSAs) for UN.GIFT. Their first PSA featured Oscar-winning actress Emma Thompson and ran on CNN for several months. A second one, titled Unaware, ran for two years on CNN and Al Jazeera English.

The work with UN.GIFT was a real eye-opener for Hemani, and the cause became a passion for him. “The stories and facts that we researched were horrendous,” he recalls. His successful endeavour led to the five-part series, with the support from UN.GIFT and End Human Trafficking Now (EHTN), an organisation established by Egypt's First Lady, Suzanne Mubarak. EHTN sees human trafficking as a problem that governments and NGOs cannot solve without the support of big business.

Hemani partnered with co-executive producer Anne Reevell of Moonbeam Films, who makes programmes for the BBC and Al Jazeera, and who secured their commission from the BBC. He also hired London-based journalist Jazzmin Jiwa as a researcher, and to help set up shoots around the world.

“Having been a print reporter before working on the series, she had the tenacity to pursue the leads we needed,” says Hemani of Jiwa, who started her career in newspapers and has six years experience as a reporter and editor. Jiwa persuaded reluctant victims, NGOs and others to speak on camera, dug up specific case information and sifted through facts and figures, and hunted for archive video material that could not be shot. “She became the one person in our organisation who now has the most information on the subject,” adds Hemani.

A global problem

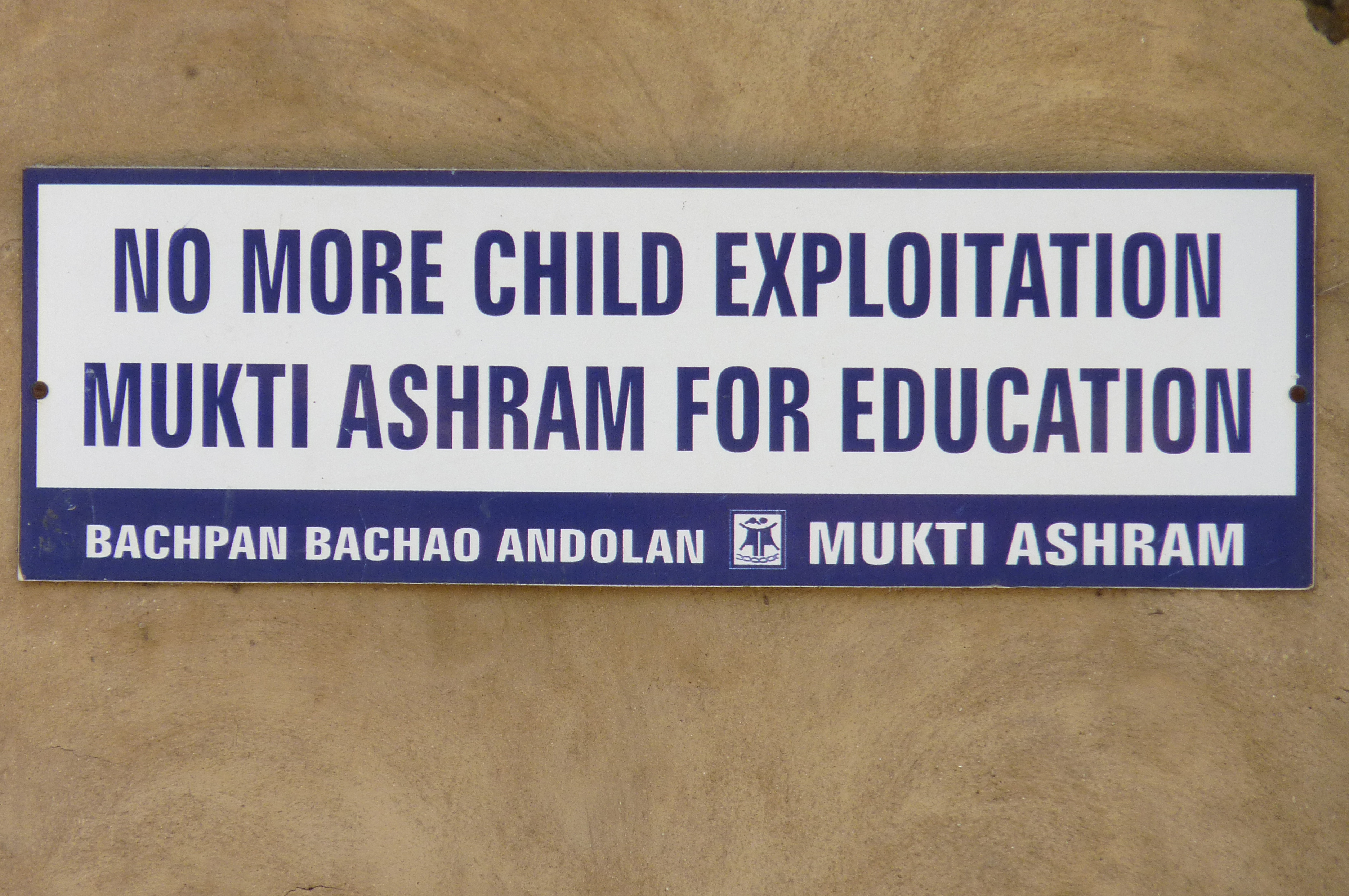

For the series, Hemani and his team examined human trafficking around the globe, including forced labour in the garment industry in India, where children are rescued from small workshops in police raids, and local NGOs help to reunite them with their parents a thousand kilometres away. They shed a similar light on child workers in tobacco fields in Malawi, as well as kids in Bangladesh and Kenya who spend long hours doing back-breaking work in makeshift quarries.

The series also looks at how poverty in some parts of Kenya is resulting in parents allowing their young daughters to sell themselves in order to put food on the table. “We were able to show how easy it was to buy a 10-year-old child on the Kenyan Coast,” says Hemani. But he adds that some hotels are now taking action to reduce the trade in child trafficking, and improving the economic and social conditions in their local community to try and reduce the causes of trafficking. The Government of Kenya is also a key participant in the International Programme for the Elimination of Child Labour, which is sponsored by the International Labour Organization and aims to eliminate child labour by 2016.

One episode introduces a young woman from Kenya, who thought she was headed for a job teaching young children in the Middle East. Instead, when she arrived, her passport was taken, mobile phone confiscated, and she found herself forced to work as a servant in a private home without pay. “She could not get help,” says Hemani. “When she ran away, the police station refused to help her. Eventually she found herself being taken to another employer – who eventually threw her off a third floor balcony.”

The woman was saved because she fell into a swimming pool, but broke both wrists and an elbow. She has since returned home to Kenya, where she has received medical treatment.

The problem of human trafficking is not localised. “We found [exploitative] domestic servitude everywhere,” says Hemani. “Not just in the developing countries, but also in the United Kingdom and Switzerland.”

Pioneering the fight against human trafficking

But in the fight against human trafficking, the team also found glimmers of optimism in an unlikely place: big international corporations.

“With businesses being key players in the global economy and holding the cards [in the lives] of so many workers worldwide, their decisions impact how many people end up as modern-day slaves,” says Jiwa. The series, she adds, “[is] unique in that it does not just reveal the stories of victims but also looks at how corporate organisations are acting responsibly, in some cases pioneering the fight against human trafficking and holding to account the ones which turn a blind eye.”

Jiwa was touched by the stories that she discovered through her work on the project, and says that it has changed the way she lives her life. “There are some [stories] that change you emotionally and spiritually,” she says. “Our choices are intertwined with the quality of life of so many others we have never met.”

Hemani agrees: “This series, we hope, will at the very least raise awareness of a crime that should shame us, if we do not open our eyes to it.”

The five-part series, Working Lives: Human Traffic, is being broadcast on BBC World News. More information, including local broadcast times can be found at the programme website.Watch the 30-second series preview here.