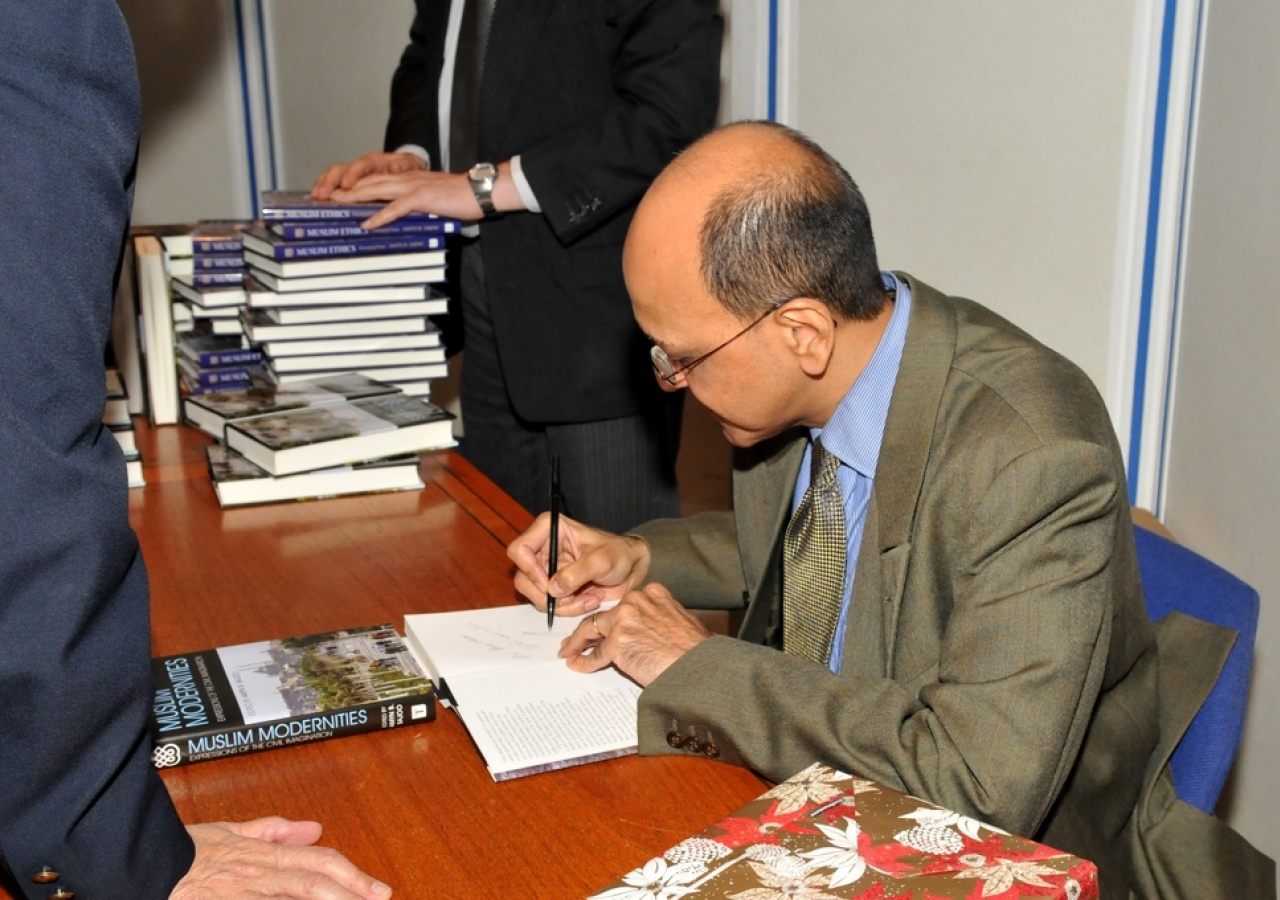

A new book, published by The Institute of Ismaili Studies and edited by Dr Amyn B Sajoo – Muslim Modernities: Expressions of the Civil Imagination – draws attention to the rich and varied nuances of the term modernity in the context of Muslim societies.

Dr Sajoo, a specialist in international rights, civil society and public ethics, understands modernity as a plural idea: modernities. If “there is more than one way to be modern,” he says, “then the quarrel will be with one type of modernity rather than with the concept of modernity in its entirety.”

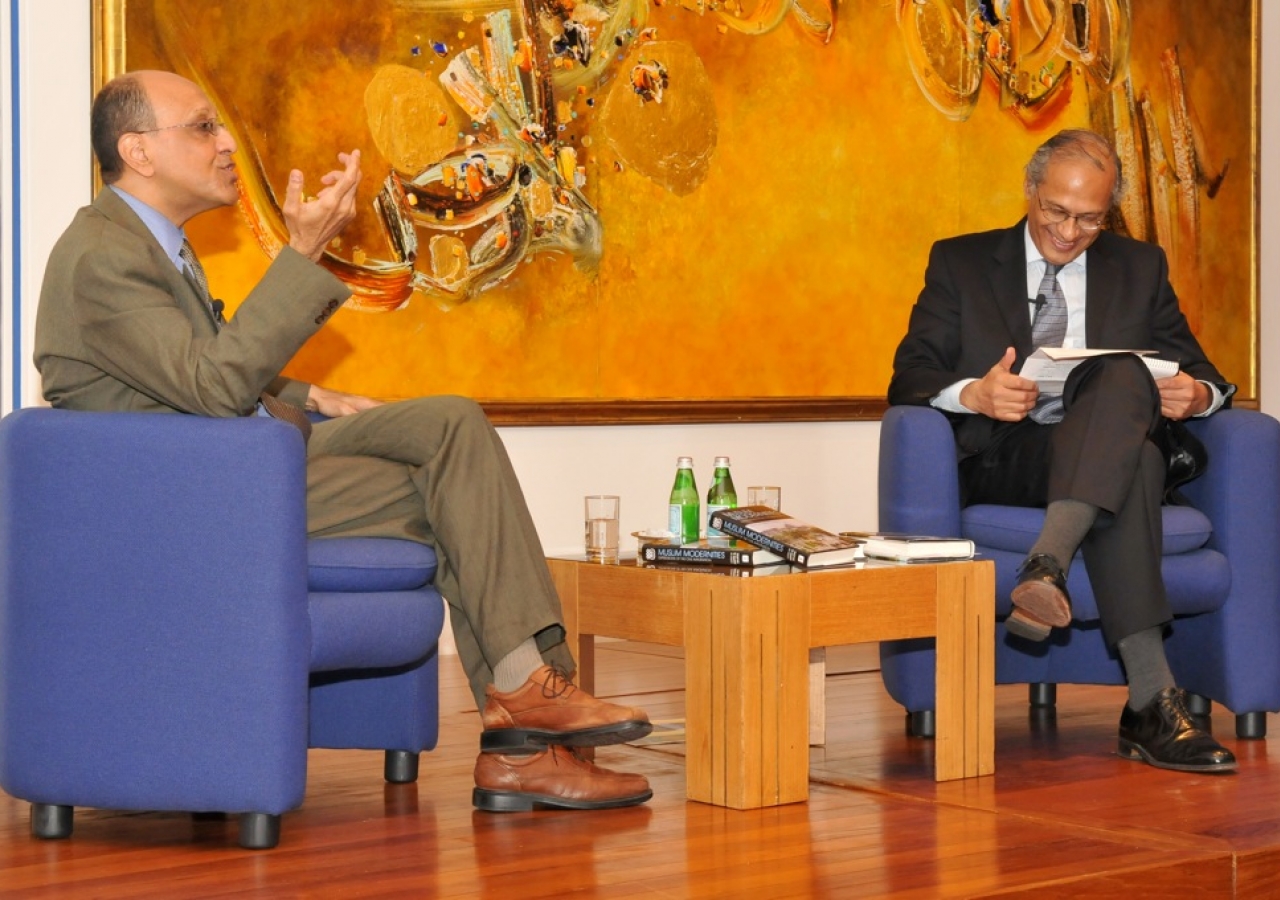

In an on-stage conversation on 2 December 2008 with writer / broadcaster Raficq Abdulla at the Ismaili Centre, London, Dr Sajoo, who lectures at the IIS where he is a Research Associate, explained how Muslim Modernities addresses core issues of identity, religion, politics, and tradition affecting Muslim societies and their relations with the rest of the world.

He asserts that it is “impossible to talk about modernity without talking about memory.” Modernity is not about ignoring the past but instead about incorporating history in the present and the future. Ignorance of history risks a loss of identity en masse.

From music and modes of dress and through politics and piety, Dr Sajoo and Raficq Abdulla interpreted the symptoms of modernity we see around us today.

Their discussion recalled Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his bold modernisation of Turkey in the 1920s and 1930s. Remembered for his secular approach to governance after the collapse of the Ottoman sultanate, Atatürk saw Europe as the proper model for progress. Yet in discarding religion and the traditions that many Turks took to be a vital part of their identity, his legacy was mixed at best. Today, many in Turkey are seeking a fresh way to be modern and Muslim.

There is also the popular reality of marketplace modernity, borne of cosmopolitan choice. The latest computers are used in madrassas, designer scarves are worn in Tehran, Indian parathas are sold in London shops. Labels such as secular, religious, eastern and western lose their meaning.

Dr Sajoo sees a constant struggle between the ideological versions of modernity, which favour social control, and the marketplace versions that promote choice. Mediating between them requires taking history seriously, since memory is critical to who we are and where we wish to go. But this does not mean passively following the past, he stresses.

Pointing to the example of the Aga Khan Music Initiative in Central Asia, he notes that the musicians involved do not simply imitate music as it was played historically. Rather, they seek to understand how a piece was composed and performed in the past and apply this thinking to their performance today. By engaging with history, they are able to reinvent it. This example is one of several “expressions of the civil imagination” that the book's subtitle promises.

The cover of Muslim Modernities whets the appetite for this discovery. The magnificent Muhammad Ali mosque is the backdrop to the fountains and foliage of busy Al-Azhar Park. Traditional and contemporary spaces come together in graceful dynamism.