“Ars longa, vitas brevis” (Art is long, life is short) is an aphorism attributed to the ancient Greek physician Hippocrates.

It has been said that art imitates life; yet, we can look back through the annals of history and see that in fact today, life imitates art, offering us a sense of déjà vu. There have been various pandemics in the past, and we should see the current coronavirus crisis in perspective, while we seclude ourselves from the world around us.

The past and the present

The Plague of Justinian in the 5th century affected Constantinople and led to over 30 million deaths, half the world’s population; pestilence was recorded at the time of the Prophet (peace be upon him and his family), with perhaps 25,000 dying during the plague of Emmaus (Syria), including some of his Companions; the Black Death of the 14th century caused 200 million deaths; smallpox eradicated 90 percent of the indigenous people of the Americas, allowing Cortez to conquer the Aztecs; and AIDS led to 35 million lives being lost.

Many historic catastrophes have been depicted by artists, perhaps the most famous and vivid canvas being “The Triumph of Death,” painted by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1562, a time between the plagues and wars that engulfed Europe. Many others have painted scenes of epidemics illustrating the despair and helplessness experienced at such times. We are fortunate that our current situation, while challenging, is no comparison to those of times past, as we have modern medicine, facilities, and hope — commodities unavailable then.

“April is the cruelest month,” wrote poet T.S. Eliot in his masterpiece, “The Waste Land.” He wrote after the First World War, when millions had suffered and perished from the ravages of battle and the 1917 influenza pandemic, misnamed the “Spanish Flu.” Europeans at the time thought they indeed faced the apocalypse.

During the next war, Albert Camus’ 1947 novel, The Plague, described an Algerian town afflicted and quarantined a century earlier due to cholera. It has been interpreted as an allegory, comparing the devastation caused by uncontrollable forces of nature to those caused by humanity out of control.

That same year, Iraqi poet Nazik al-Malaika wrote about the agony of cholera engulfing Cairo, a grief-stricken city with 10,000 deaths. It is instructive to read her poem and contrast the description to our own times, despite our healthcare system being strained to capacity.

“It is dawn.

Listen to the footsteps of the passerby,

in the silence of the dawn.

Listen, look at the mourning processions,

ten, twenty, no… countless.

…

Everywhere lies a corpse, mourned

without a eulogy or a moment of silence.

…

Humanity protests against the crimes of death.

…

Even the gravedigger has succumbed,

the muezzin is dead,

and who will eulogize the dead?

…

O Egypt, my heart is torn by the ravages of death.”

Tripoli, Libya, was also afflicted by the plague in 1785. Miss Tully, an English resident at the time, wrote about fumigation and social distancing, as well as the spread of the disease to Sfax, Tunisia, where 15,000 perished — half the town’s population.

Even earlier, in 1349, Syrian historian Ibn al-Wardi, in “An Essay on the Report of the Pestilence,” described the Black Death with an eerie similarity to what we face today.

The plague began in the land of darkness. China was not preserved from it. The plague infected the Indians in India, the Sind, the Persians, and the Crimea. The plague destroyed mankind in Cairo. It stilled all movement in Alexandria. Then, the plague turned to Upper Egypt. The plague attacked Gaza, trapped Sidon, and Beirut. Next, it directed its shooting arrows to Damascus. There the plague sat like a lion on a throne and swayed with power, killing daily one thousand or more and destroying the population.

Al-Wardi ends with a prayer: “Oh God, it is acting by Your command. Lift this from us. It happens where You wish; keep the plague from us.” He was to succumb to the disease himself two days after completing his work.

The prescience of

Contagion

Film buffs may be familiar with some recent productions that have dealt with imaginary epidemics. They include the 1995 film, Outbreak, starring Dustin Hoffman, and Contagion, which describes societal collapse following a virus pandemic, one of the latest in this genre. It does, however, end on a positive note, with the line, “Society is better off in a plague when everyone works together and cares for one another, and tries to muddle through a nightmare.” Certainly, an apt description of what we are witnessing today, as we grasp at numerous potential solutions for salvation.

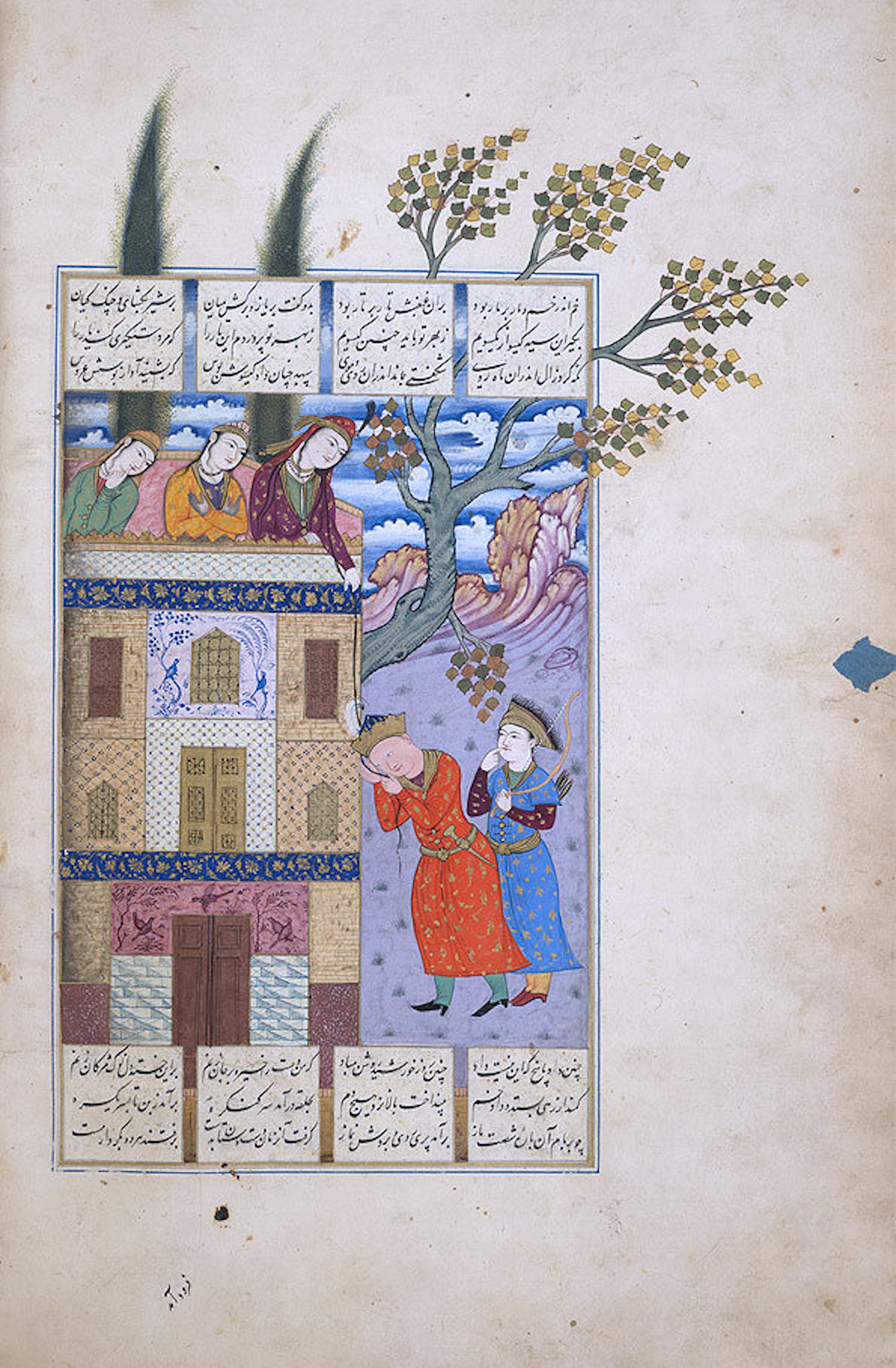

The acclaimed South Korean film, My Secret Terrius, mentions coronavirus and depicts social distancing as a prophylactic. And the popular animated children’s film, Tangled, tells us that Rapunzel lived in the kingdom of Corona, was kidnapped by a witch, and imprisoned in a tower. Children today will relate to the main character in this tale: claustrophobic and unable to play outside. This story may have its origins in the story of Rudabeh, found in the Persian epic, the Shahnameh of the 11th century.

History repeated

Rudabeh

“There is no present or future — only the past, happening over and over again now,” wrote playwright Eugene O'Neill. It certainly seems so, as we recall bubonic plague, tuberculosis, typhoid, cholera, the “Spanish Flu,” polio, AIDS, SARS, and Ebola — just a few of the epidemics that have decimated populations in recent memory and recorded in great detail in historical accounts, as well as in art and literature.

In our globalised world, the threat of disease is even more palpable now, as populations cross frontiers in a matter of hours, perhaps carrying with them invisible microbes.

We can recall the leadership of Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah during the bubonic plague that engulfed Bombay in 1897. He provided facilities and supported the research of a vaccine there that eventually countered the disease. As the public was wary of the vaccine, he led by example, writing in his Memoirs: “It was in my power to set an example. I had myself publicly inoculated, and I took care to see that the news of what I had done was spread as far as possible and as quickly as possible.” Emboldened by his example, countless others in the city followed.

The threat of pandemics was noted by Mawlana Hazar Imam in his 2010 LaFontaine-Baldwin lecture, when he said, “Almost everything now seems to ‘flow’ globally — people and images, money and credit, goods and services, microbes and viruses, pollution and armaments, crime and terror.” The veracity of that observation is clear.

Lessons from the pandemic

What do these impressions of life and death by artists, poets, and novelists inform us about conditions today? Perhaps the most important lesson is that of humility, that nature is a force far greater than the ability of humanity to control and mould to its will. Whether it be weather-related events, natural disasters, or epidemics, we have limited responses.

We have been given a collective shock with the realisation that we are in fact not masters of the universe, and our ability to determine the future is not all in our control. However, there are actions that can be taken to mitigate disasters for the human race and its future. This may be a warning to show greater concern for the environment, as Pope Francis suggested recently. We do understand the causes of environmental degradation, and that the environment must be protected and nurtured, as it is the source of life, from the water we consume, to the trees that offer us shade and the clean air we breathe.

In our march for progress, humans have polluted the atmosphere, the rivers, and the seas. Yet, an unseen microbe can be the cause of destruction, affecting anyone and everyone, from the leaders of countries, to the rich and poor alike, and even to the remotest tribe, the Yanomami, hidden deep in the Amazon forest. Indeed, scientists have suggested a link between deforestation and the rise in infectious diseases, of which the Amazon region is a prime example.

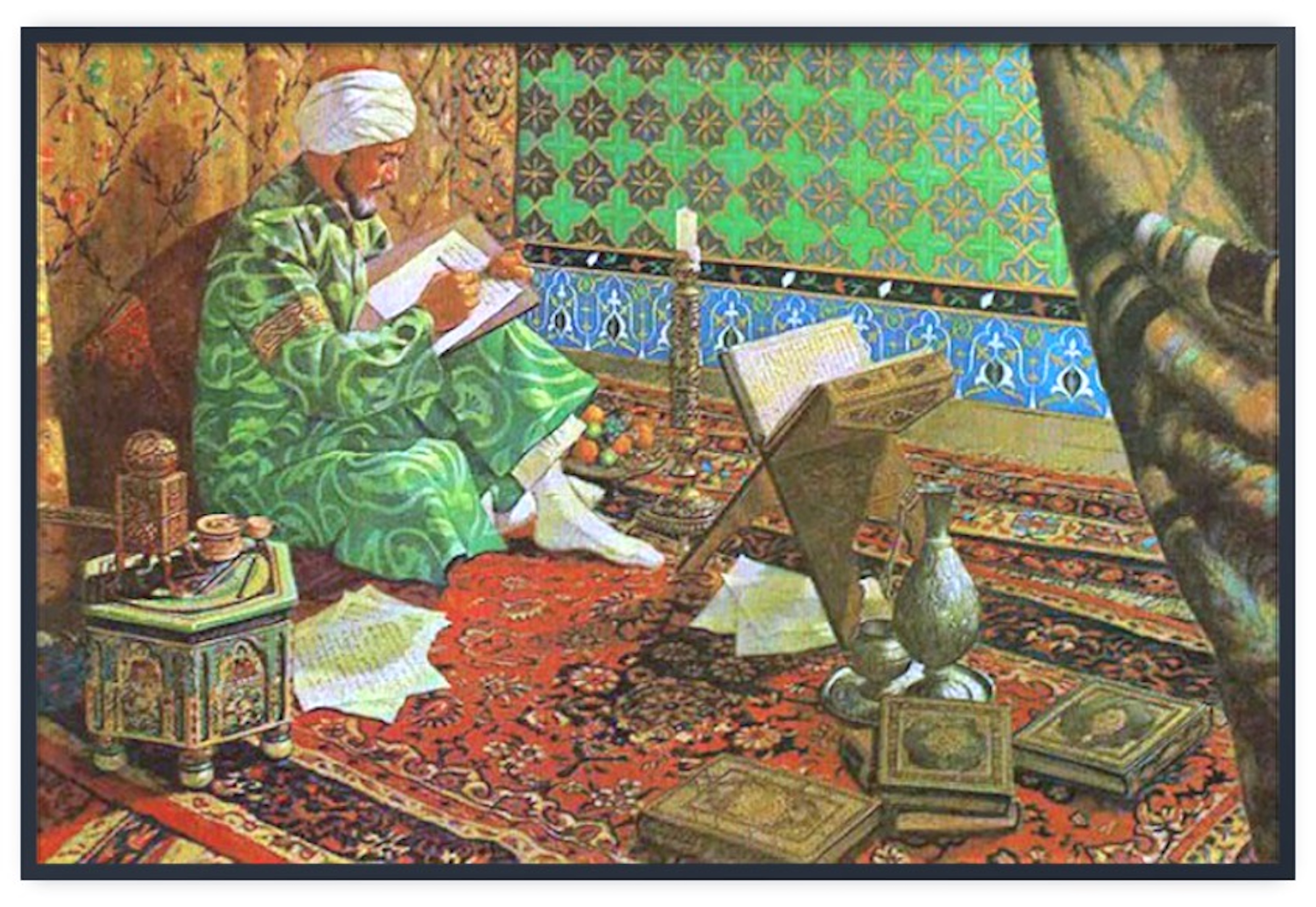

Ibn Sina

Today’s heroes

Traditional wars are fought and won with soldiers, superior weapons, military strategy, and tenacity. None of these are useful for today’s global threat. It is the doctors, nurses, emergency personnel, farm workers picking vegetables and fruit, delivery drivers bringing us supplies, and the grocery store staff on the frontlines, risking their lives in a war to save the rest of us, sometimes losing their own. They are the soldiers of today, heroes and heroines who deserve medals in their effort to fight this scourge, and who offer us hope.

Our own Ismaili healthcare workers all over the world are a part of this contingent of soldiers, working in the emergency rooms and ICU wards. Others from our global Jamat have offered personal protective equipment from their stores, made and donated masks, as well as food and needed items to hospitals, neighbours, and others. We are all in this together.

This crisis will end but it will not be forgotten, as there are lessons here for future generations. And because artists and novelists are keen sensors who reflect the social conditions of their time, this episode in history, with its impact, failings, successes, and new soldiers, will be revisited, recalled, and immortalised, both in word and paint — for life may be short but art transcends time.