Decades ago, Bangladesh – then known as East Pakistan – was home to a thriving Jamat. Ismailis were active in key industries including jute, textiles, steel, aluminum, leather, construction, and food processing, as well as trading, banking, insurance and hotels. The community was spread across the country, including major cities – Chittagong, Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Narayanganj, Rangpur, and several others.

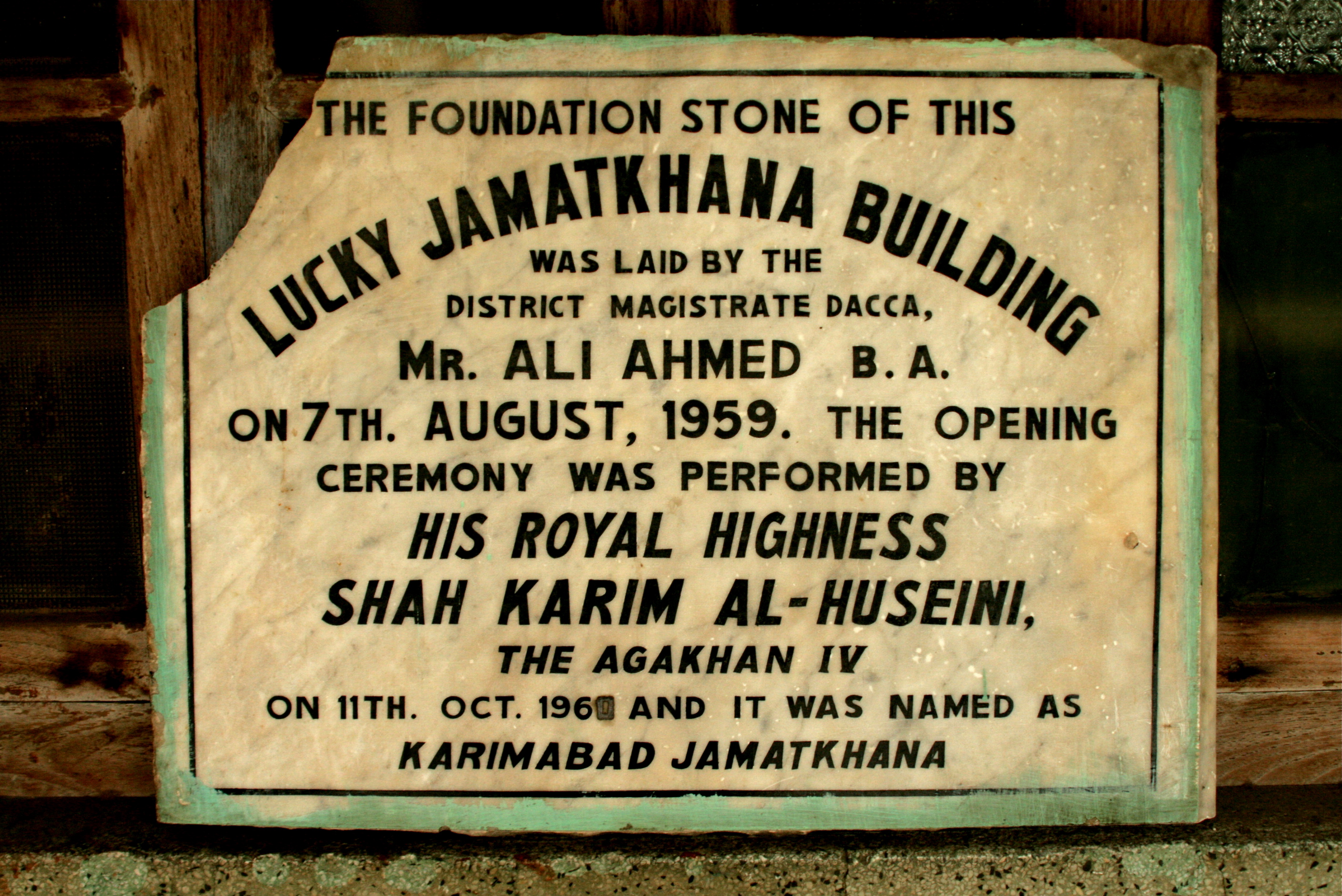

Layed in 1959, the foundation stone of Karimabad Jamatkhana recalls a thriving Jamat in Dhaka and throughout Bangladesh. Ayeleen Ajanee Saleh

Layed in 1959, the foundation stone of Karimabad Jamatkhana recalls a thriving Jamat in Dhaka and throughout Bangladesh. Ayeleen Ajanee Saleh“We had a large and active Jamat and were known as a strong business community,” recounts one long-time resident. Many still remember Mawlana Hazar Imam's first visit to Dhaka in 1958, which filled up an entire stadium.

But in 1971 war broke out, resulting in the flight of millions of civilian refugees to India and West Pakistan. Some even fled further afield to Canada and the United States.

One member of the Jamat recalls: “I was the only member of my family who stayed behind to look after our house, while my parents, brothers and sisters left for India.” During the war, he provided a shelter to fellow Ismailis whose homes were destroyed or taken away.

After liberation, various industries were nationalised under the economic policies of the government of the day. The impact was felt by many Ismailis, whose businesses were forced to close. The country struggled to rebuild itself and even those Ismailis that remained had few options but to seek a brighter future abroad for themselves and their children. “The combination of the war and the lack of resources to cope with cyclones had crippled the country,” said one member of the Jamat.

Karim Noorddin stands in front of three buses from the transport business that he and his brother established in 2007. Ayeleen Ajanee Saleh

Karim Noorddin stands in front of three buses from the transport business that he and his brother established in 2007. Ayeleen Ajanee SalehDespite the difficult challenges of the period, the Ismaili Imamat and the Jamat maintained a presence in Bangladesh. In 1980, the Aga Khan Foundation began working with local partners on projects in rural development, microfinance, and education. The Aga Khan School in Dhaka, founded by the Aga Khan Education Services in 1988, established itself among the top academic institutions in the country. Other civil society institutions such as the Grameen Bank and BRAC (formerly the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee), as well as the enabling policies of the Government of Bangladesh, also contributed to improving the country's economic conditions.

Today, Bangladesh is re-emerging as an area of economic interest to both the Jamat and the wider international community. With the advent of globalisation, many of the world's largest corporations have sought to leverage the country's low-cost labour pool. Foreign remittances have also fuelled the growth of local businesses, raised household disposable income and savings, and drawn the attention of Bangladeshis who had migrated to the West. Ismaili entrepreneurs have begun moving back into the country as well, sometimes with the facilitation of the Ismaili Council for Bangladesh.

Karim Noorddin moved to Dhaka from Cuttack, India in 1998, soon after he graduated from university. He joined his brother Nizar, who had moved to the city three years earlier. Karim was attracted by employment opportunities in Ismaili-run businesses. “Learning Bangla was a challenge,” he recalls, “but factors like Bangladesh's proximity to India, the opportunity to gain practical experience, and also the success stories and support from friends, made it worthwhile.”

Initially working at an Ismaili business, the brothers went on to start a transportation business in 2007 with the support of the Ismaili Council's Economic Matters Committee.

A view of the busy factory floor at the Currimbhoy family's growing garments business. Zafar Currimbhoy

A view of the busy factory floor at the Currimbhoy family's growing garments business. Zafar CurrimbhoyFormer Dhaka resident Nazir Currimbhoy, decided to move back to the country in 1996 to pursue opportunity in the growing garments business. In 2007 he was joined by his son Zafar, a recent MBA graduate from the London Business School.

Walking away from recruiters from corporations in the United Kingdom and the United States, the younger Currimbhoy decided to follow his father's entrepreneurial path. “Adjusting to the business culture was a challenge,” he says, “but since Dad's business was already set up, it was much easier to get started.”

One advantage that he brings to the business is that clients in the West can communicate with him easily, and are comfortable dealing with someone who follows professional standards that they are familiar with. The Currimbhoys' business employs over 130 employees and sources garments from over 70 factories and other suppliers in Asia for clients in Europe and North America.

But no opportunity is without risk. Even for those who have lived in Bangladesh in the past, and who speak the language and understand its business culture, the environment can be challenging.

One member of the Jamat who had moved back in 2008 says: “Things often move slowly when dealing with government permissions so you have to be patient.” He continues to push ahead with optimism, but advises people considering Bangladesh to do their research and ensure they are confident before making the move.

More Ismailis have been back to Bangladesh since Mawlana Hazar Imam's Golden Jubilee visit in 2008. Former residents like Karim Rahim, whose family moved to Los Angeles in 1991 when he was only 10 years old, are seeing the country in a new light.

Driving through the streets of Dhaka, Rahim noted that despite the need for long-term improvements in key areas such as infrastructure and energy, he “saw a completely different Bangladesh.” In parallel with recent projects and investments of the Ismaili Imamat, such as the Aga Khan Academy in Dhaka and a new Ismaili Centre, the country's development continues to unfold in a promising direction.