In the first part of this article, we explored definitions of architecture, and the complexities involved in designing buildings and spaces in the modern world. If buildings and cities do indeed ‘speak’ to us, then what should they speak of?

Over recent years, there has been a broadening of the original definition of architecture and its significance; how it serves as a metaphor for society, a prism through which the several constituent elements that comprise a culture can be viewed with greater clarity; how a society expresses its world view; how it wishes to project its character to others and how, ultimately, it views itself.

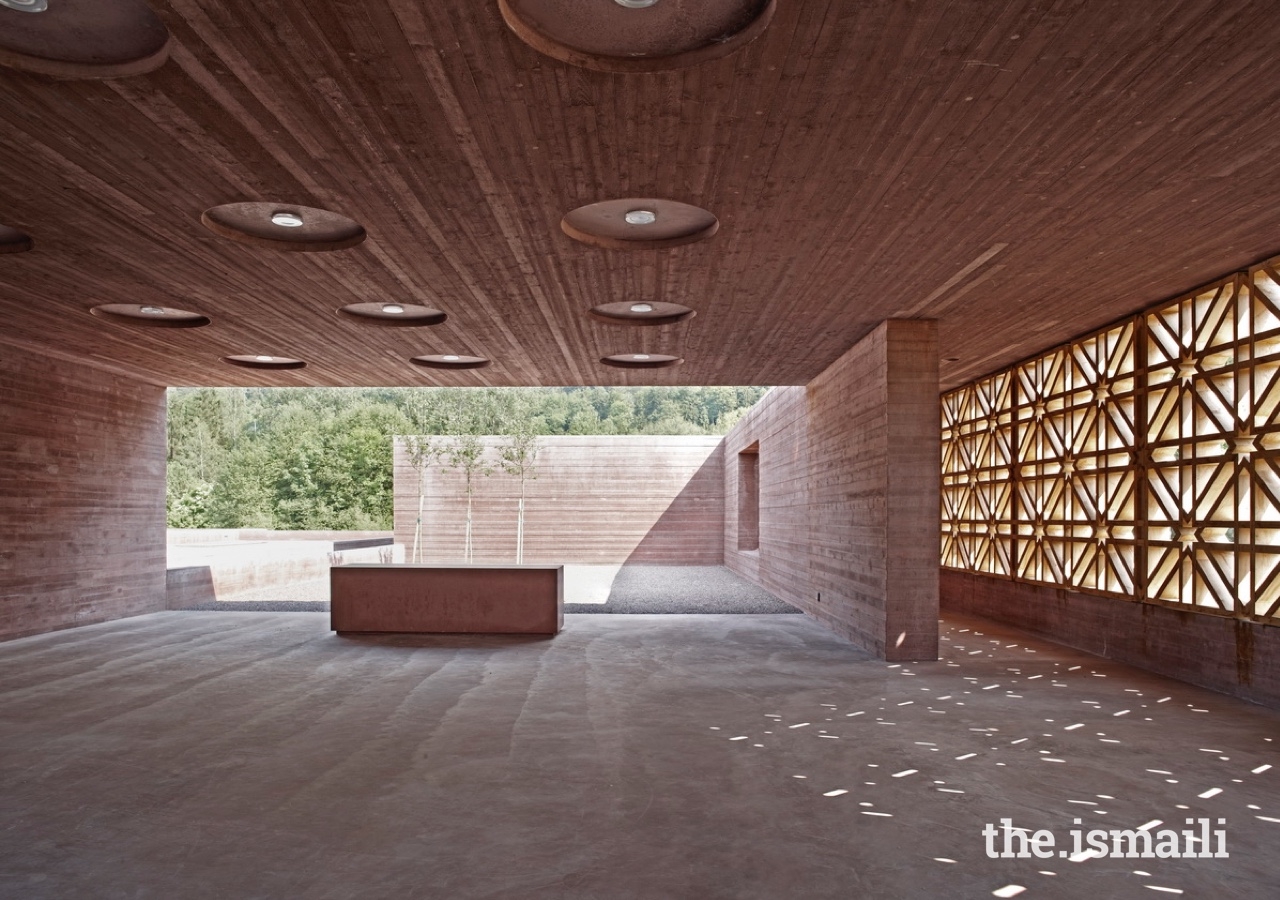

“What the Muslim world needs today,” suggested Mawlana Hazar Imam in Cairo in 1989, “is more of those innovative architects that can navigate between the twin dangers of slavishly copying the architecture of the past and of foolishly ignoring its rich legacy.”

When development is viewed “only through the lens of an economic or materialistic conception, we seriously devalue and impoverish the idea,” says Professor Azim Nanji, suggesting that the quality of life of societies and individuals also encompasses their cultural and social lives, cornerstones of their identities. “Architecture is one significant manifestation of that sense of belonging and place,” he says, and reflects or affects how their daily lives are organised around spaces within which people interact with others. “It is through Architecture that they identify markers of their past and present. In a broader sense, it is as part of a total environment that they can explore their sense of being in the world,” he adds.

While extravagant, iconic buildings and their architects are the most celebrated in wider discourse, the Aga Khan Award for Architecture is more concerned with recognising projects that: contribute positively to improve the built environment through their use of materials and technology; that reflect a culture's traditions and history; that reflect a societies aspirations; and, that impact the community's quality of life in an economic and practical manner. Modernisation, industrialisation, urbanisation, housing, sanitation, education, healthcare, public space, and the natural environment, have all factored in the selection process, over and above the artistic merits or design features of a project.

Architecture has an additional dimension also, as Hazar Imam said in Indonesia in 1995. “Spirituality and architecture, together, become a force that can build bridges between people and communities, and empower them to build a more harmonious and humane future.” The Aga Khan Award seminars and Jury deliberations are opportunities to discuss the objectives of architecture, its symbols, creativity, use, and impact in Muslim cultures.

Perhaps one of the most significant areas in which the Award has made an impact is in “shifting perspectives and thinking about Architecture and its relevance to Muslims and their immediate contexts of rapid change,” notes Professor Nanji, “and that beyond mere design there is a role for Architecture in promoting environmental and social betterment and of the continuing role of inherited architectural practices and spaces.”

Significantly, he notes that the restoration of the architectural heritage of Muslims has also begun to receive greater attention, based on the activities of the Award. Through its identification of architectural excellence and practices, the Aga Khan Award has also raised awareness of why the built environment remains crucial in the development of Muslim societies and indeed, of all peoples sharing a planet facing multiple risks.

In 1998, Robert Campbell wrote in the Architectural Record that, “the Aga Khan Award is the wisest prize programme in architecture. It's the most serious, the most thoroughly researched, the most thoughtful.” Maria Bertolucci, in a 1997 Metropolis magazine, went further, writing that the Award is “exceptional,” and that it “attempts to reframe the issues, establishing architecture as an integral element of Islamic culture, and fosters a modernity that embraces intellectual and technological progress, but not at the expense of cultural identity, spirituality or the earth.”

While it is difficult to quantify the impact of the Award on architects and buildings in the Muslim world, and although it is complicated to determine its practical influence on design, there can be little doubt that it has added much intellectual depth to discussions about buildings, urban design, and the built environment, even in countries beyond the Muslim world.