As an architect myself, I have always been fascinated by how architecture can encompass all aspects of an individual’s life, from secular facets of aesthetics, beauty, functionality, and use of space; to the emotional and often intangible aspects of experience, feeling, and – if one is open to it – opportunities for spiritual encounter.

In the words of the philosopher and author Alain de Botton “One of the great but often unmentioned causes of both happiness and misery is the quality of our environment: the kinds of walls, chairs, buildings, and streets that surround us.” As such, architecture and our built environment has a profound impact on our everyday needs.

Similarly, Mawlana Hazar Imam explained in a speech in 2016 that, “Architecture is the only art form which has a direct, daily impact on the quality of human life.” This is why, I think, Hazar Imam places so much importance on this topic. It matters to him because it matters to us all.

In the 1400-year Muslim tradition of leadership, an Imam is concerned not only with interpreting the faith, but also with improving the quality of life of his community and all those amongst whom they live. For the Ismaili Imamat, “quality of life” represents a holistic vision that encompasses the entire ethical and social context in which people live, of which architecture forms an integral role.

Perhaps we can understand this better by looking through the lens of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture, which Hazar Imam established in 1977. Every three years, the AKAA brings about a buzz of interest among the architectural profession and beyond. This year’s winning projects follow in a long tradition of excellence and have yet again raised the bar for design innovation and inspiration.

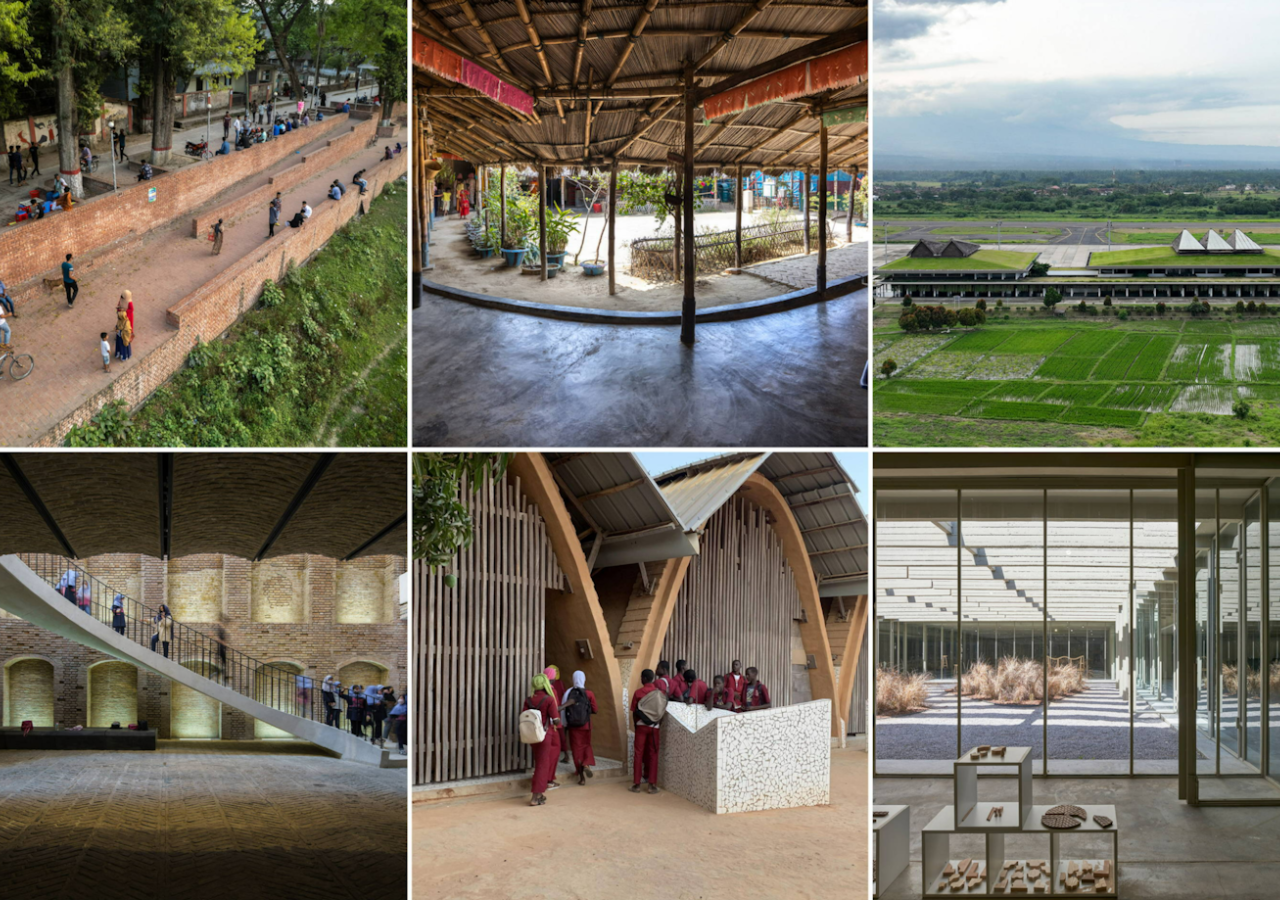

The six winners, from Indonesia, Senegal, Bangladesh, Iran, and Lebanon respectively, were acknowledged by the Award’s Master Jury for successfully addressing the needs and aspirations of predominately Muslim societies in a number of fields.

By acknowledging excellence in these fields, the Award invests with a social conscience in people, in their intellectual pursuits and in the search for new and useful knowledge. In a speech made in Ottawa in 2013, Mawlana Hazar Imam spoke of the impact of architecture on the way we think about our lives. “Few other forces,” he said, “have such transformational potential.”

Just as in previous cycles, this year’s winners contribute towards improving the material condition of the communities in which Muslims and others live.

The Community Spaces project as part of the Rohingya Refugee Response, for example, gives agency to communities over their own destiny, through the gift of architecture. Located in Bangladesh, the project comprises a group of six sustainably built structures in the world’s largest refugee camps, housing those fleeing violence in Myanmar. Remarkably, the structures were built collaboratively in the field without drawings or models. Whether built around existing betel nut trees, instead of cutting them down; using colourful mattresses as roof insulation; or calling on skilled bamboo workers to build complex roof trusses; the project champions social, climatic, and sustainable agendas, whilst providing employment opportunities that celebrate the community’s innate talent.

Similarly, the Renovation of Niemeyer Guest House in Lebanon involves the transformation of a pavilion into a design platform and production facility. It promotes Tripoli’s long-established but recently declining wood industry with fully reversible interventions. The project has boosted the industry’s presence nationally and internationally, spurring work on a conservation plan for the entire site whilst promoting economic development through revived employment in the sustainable wood industry.

The Urban River Spaces project in Bangladesh is another community-driven initiative, providing public space in a riverside city with 250,000 residents. Locally available materials such as brick and concrete were used in the simple, contextual designs, and all existing trees and vegetation were retained. Built by local builders and masons, the project created opportunities for work in an environmentally conscious way.

One of the principles many Muslims abide by is the connected nature of faith and world. Mircea Eliade explains in his book The Sacred and the Profane that the sacred always manifests itself as a reality different from normal realities and that we only become aware of the sacred when it reveals itself as something different from the secular. In Islam, however, life itself is considered sacred and, therefore, the sacred also encompasses the secular. During his Silver Jubilee in 1982, Mawlana Hazar Imam said “In Islam, man is answerable to Allah for whatever he has created, and this is reflected in its architectural heritage... Since all that we do and see resonates on the faith, the aesthetics of the environment we build, and the quality of the social interactions that take place within these environments, reverberate on our spiritual life.”

Islam also places significant emphasis on the physical environment in which we live. In our role as trustees of God’s creation, we are tasked with leaving the world for future generations in a better condition than we found it. The demonstration of this principle is another aspect that the Aga Khan Award celebrates, and one that this year’s winners exemplify.

For example, Banyuwangi International Airport in Indonesia embraces a context-conscious design approach, catering to the hot climate through a large-scale, contemporary interpretation of functional design principles. Openings and overhangs are optimised for temperature control through natural ventilation and shading, with a conscious selection of materials based on local availability and low-cost maintenance, demonstrating excellence in sustainable design.

Similarly, the Kamanar Secondary School in Senegal utilises the region’s most abundant material, clay, with creative forms that celebrate the material’s natural properties. Clay vault modules were produced by volunteers using local techniques, demonstrating the ethic of mutual support and collaboration, enclosed with wooden lattices, which allow light in. The clay and lattices also act as an evaporating cooler mitigating the need for any mechanical air-conditioning, thus reducing the building’s carbon footprint.

Winning projects are often aspirational structures that create a benchmark for innovation, typically with strong social, environmental, economic, cultural, and restorative agendas. An example is the Argo Contemporary Art Museum & Cultural Centre in Iran, a restoration masterpiece housed in a century-old former brewery, abandoned for decades. With an interesting dialogue between new and old, all fresh insertions are curvilinear, employing distinct materials that differentiate them from the brick-built historic fabric. Innovative design and structural ingenuity allow for generous ceiling heights in the climate-controlled galleries, with striated and pitched roof structures acting as deep, filtering skylights.

The underlying design ethos demonstrated by these projects broadly reflect the ethical principles of Islam. Whether through building to improve living conditions or building in harmony with the natural environment, this year’s winners of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture inspire us all to build with the future of humanity in mind.