Dreams do come true, Sada reflects; as a young boy in Karachi, not from an affluent family and with eight other siblings, he would gaze at the large mansions in the city and the large cars passing by. “These belong to the rich, leaders, and ambassadors,” his mother told him. He replied, wistfully, “One day, mummy, I’m going to be an ambassador and have a big car.”

Two degrees later and with his new wife, Mumtaz, he arrived in Florida to join his three siblings. He invested in a small business, later moving to Midland, Texas, and then to Austin, and became a successful entrepreneur.

Sada identified himself as a pragmatic Republican of the party’s centrist wing, much like Colin Powell or the Eisenhower Republicans of an earlier era. He had the opportunity to interact with Governor George W. Bush and Lieutenant Governor Rick Perry. Soon after, he was appointed on the board of the Texas Enterprise Fund, a $200 million emerging technology fund, the Texas Business Council, as well as on the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board.

Sada next became President of the Ismaili Council for the Southwestern United States, and was part of the team involved in the opening of the Ismaili Jamatkhana and Center in Houston, as well as the related visit by Mawlana Hazar Imam.

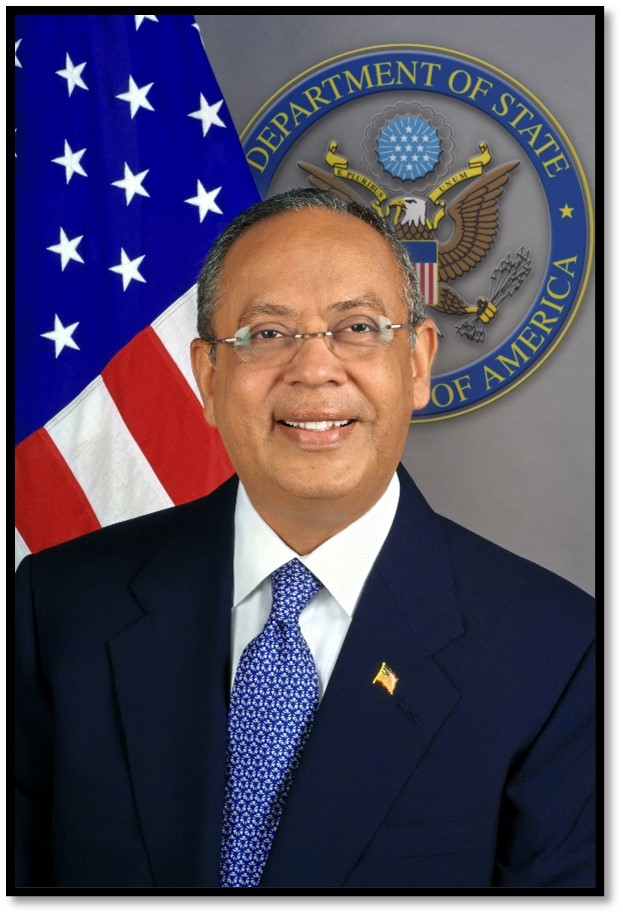

Sada Cumber

In 2005, Sada took on a diplomatic post as Honorary Consul General for the Republic of Malta. Then, in 2008, President George W. Bush appointed him as the first US Special Envoy to the 57-member of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC).

The ismaili.usa asked Ambassador Sada about his experiences as a diplomat and what he learned. He noted that these views are his own and do not represent any community or group.

1. What did President Bush tell you about the purpose of being the US Envoy to the OIC?

The President did not micromanage. He trusted his people to make good decisions. So saying that, “There is an opportunity for you to do something multilateral and work with the Muslim world,” was about as explicit as he was with his instructions. Instead, I determined my agenda by talking to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, Counter Terrorism advisor to the President Juan Zarate, and others.

We thought we should reach out to the political and religious leadership of Muslim-majority countries and establish dialogue at the White House level. We wanted to try to secure international recognition for Kosovo, increase counterterrorism cooperation, and explain that the US was not at war with Islam.

I also wanted to work with the US security and intelligence agencies to ensure counterterrorism efforts did not hinder Muslim Americans’ practice of religious obligations, such as prayers and zakat funds that are properly managed and distributed.

2. Did you encounter any challenges as the Envoy?

The challenges were more personal rather than professional. While I was living in Washington, my family remained in Texas. I rarely saw my friends and family. Managing time became a challenge as I had numerous meetings at the White House, State Department, CIA, and other agencies, and had to travel to meet heads of states and other high

Pres Bush

officials around the world. My trips abroad were very short. Due to the high level of security protocols, no tourism was possible, and it was frustrating to visit so many wonderful places and not be able to appreciate all that they had to offer.

3. How many countries did you visit as Ambassador? What kind of reception did you receive?

I visited more than 40 nations, several of them on multiple occasions. Obviously, each meeting had its own specific agendas, but the overall trend was clear. I began my appointment at a period of intense skepticism about the US in the Muslim world and my earliest meetings reflected that. But when I sat down with the leadership, it was very gratifying to see how quickly we understood and agreed that while we might differ on means, we wanted most of the same things. Also, the foreign leaders knew that I had the ear of the President and the Secretary of State to whom I was directly reporting, and that added a great deal to my credibility.

Sada with Pope

4. What impact did you have as Envoy?

I was able to deliver in all the major areas we identified at the beginning of my service. I met with figures such as Pope Benedict XVI and King Abdullah to promote interfaith and intrafaith dialogue as tools for peace. Our efforts encouraged four additional nations to recognize Kosovo, and, at the time of my departure, nine other nations were taking steps in that direction. We secured from the OIC an explicit and vigorous condemnation of suicide bombing by both Shia and Sunni scholars. On behalf of the US government, I led, negotiated, and signed the very first agreement of cooperation with the OIC.

To allow Muslim-Americans to safely meet their faith obligations, I worked with the US Department of Justice and the governments of several Muslim nations to create a list of Islamic charities that were in compliance with US counterterrorism regulations. I also persuaded the Justice Department to shift enforcement of regulations to distributors of funds rather than donors, protecting individuals who unwittingly and in good faith contributed to questionable organizations.

I tried to arrange a summit at the White House for top Muslim NGOs to foster cooperation with the US in enhancing the quality of life for the Muslim world’s least developed nations. Although it did not materialize, all of this built toward the goal of a first-ever visit by top OIC officials to Washington.

As much as these were tangible accomplishments, I feel that one of our biggest impacts was changing the tone in the dialogue between the US and the Muslim world.

5. What are you doing now?

I continue to be involved with entrepreneurship. However, I am moving beyond just the technology space. Presently I am engaged in investment banking, technology, fintech, digital healthcare, impact investment, and consulting in areas which directly address global challenges.

Just as importantly, I write and speak widely on topics related to diplomacy, national security, developmental assistance and foreign aid, American politics, Islam, and relations between the West and the Muslim world.

Although I had been a Republican almost since I became an American, in 2020 I joined with more than 100 other Republican former national security and diplomatic officials in calling on Americans to support Joe Biden for President.

One of the most exciting opportunities I ever had occurred in February when I was asked to deliver the keynote address at the “Imam Ali – The Spirit of Reform” conference.

6. Can you tell us more about this conference and your comments there?

I took the opportunity to focus on issues of the empowerment of women, education, economics, and civil society. The reaction to the keynote has been phenomenal. I received more compliments and more requests for copies of my remarks than I can count. That speech was one of the greatest moments of my life. The event was televised live on Ahlebait TV in the UK, reaching an audience of up to two million in over 92 counties, including some of the world’s foremost Ulema and Shia scholars.

I noted the importance of Imam Ali’s letter to Malik al-Ashtar, Governor of Egypt, on governance, requiring a ruler to pay heed to the needs of the weakest in society, and his emphasis on deeds over rituals, and personal communion over public piety.

Portrait with Sheikh

I mentioned the Imam’s desire to improve the quality of life of all people, his attitude towards women and the need to nurture them to have roles in social, economic, political, and educational spheres. On education, Imam Ali framed it as both a duty and right, and the intellectual tradition within Islam owes much to his vision. On civil society, Islam has a long history of guilds, tariqas, waqfs and other groups that played this role.

7. Can you share your thoughts on Sunni/Shia political tensions?

I noted in my keynote address, that Muslims dissension should not lead to the same confrontations faced by medieval Christian groups that led to further divisions, and even war between them.

In many ways, Sunni-Shia differences have been co-opted for purely political reasons, which fan resentment and further misunderstanding. Non-Muslim actors carry some blame as well. The reductionist foreign policy narrative of the US, and to a lesser extent Europe, and Shia-bashing have not helped. Neither has Israel’s willingness to feed that narrative as a means for keeping pressure on Iran and a significant US security presence in the region.

“There is no compulsion in religion,” according to the Holy Qur’an. So we need to be more accepting of differences in history, tradition, and practices, and become a more pluralist faith. Shi’ism encourages engagement of the intellect (aql) and reasoning, and so our efforts should be to educate and elevate the younger generation so they can lead us to a better, peaceful, and safer environment, and work to improve the quality of lives of all people.

8. How is the US viewed in the Muslim world today?

We need to draw a distinction between the US government and the US society. Regarding the former, outside of certain segments of the GCC nations, the answer could be charitably characterized as “not good.” I know so many people in the Muslim world who wish to be hopeful about the Biden administration, but they have been burned before, and that makes hope hard. And while President Obama wanted a reset with the Muslim world, the actual results were mixed. So, despite the desire, genuine optimism about the new US administration is hard to find.

The view of US society, however, is a very different question. Recently, when Iran signed its $400 billion cooperation agreement with China, I heard from so many Iranians that they wished Iran and the US could be building bridges rather than Iran and China. And, as I like to point out, it is easier to practice the Islam of your conscience in the United States than it is in many Muslim-majority countries.

9. What has been the impact of recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital?

I believe US recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital was a wrong decision. It further complicates the already severe problems between Palestine and Israel. But we need to keep it in perspective. There are Muslims, Westerners, and Israelis, who use this decision as a drum to keep animosities high and as “proof” that there can be no progress or détente between these groups. This is dangerous. Palestine and Israel are not the whole of Muslim-Western relationship. Further problems there, real as they may be, do not preclude meaningful progress in other areas. I am hopeful, but we may have to wait a long time to see progress here.