After a multitude of tests, the doctors informed Mehreen that Alesha had a rare form of bone marrow disease—so rare that only 14 people in the world are diagnosed with this. Bone marrow disease, the Kajani family soon learned, is a type of cancer that affects the blood and bone marrow. Nine-month-old Alesha would have to fight for her life.

Upon diagnosis, matters progressed swiftly. Alesha was in a hospital more than she was at home. She started receiving blood transfusions four to five times a week. During blood transfusions, a doctor or nurse placed a small needle into the vein, then the blood moved from the bag through a rubber tube into the vein through the needle. Vital signs were monitored very carefully throughout the procedure to make sure Alesha’s body accepted the blood and no adverse reactions occurred.

Horrific side-effects ensued. Alesha stopped eating. A peripherally inserted central catheter line (PICC) had to be entered. The PICC line allowed for total parenteral nutrition (TPN), which is a method of feeding that bypasses the gastrointestinal tract. Alesha would get the nutrition she needed in order to survive. She was still getting transfusions, had numerous infections, and was in and out of intensive care. At one point, just when Mehreen thought Alesha was out of the woods, she had yet another life-threatening reaction.

“There is nothing like watching your daughter’s vital signs drop as a medical team tries to keep her alive,” Mehreen said.

Nearly insurmountable fear and grief plagued the Kajani family’s multiple nights in the hospital. But that would not let the family lose hope and faith that better days were coming.

How did Alesha get this disease? Unfortunately, it’s hard to identify what the underlying factors were that triggered the disease to become active. One known cause is through genetic and ethnic background. In fact, studies show that bone marrow disease is more likely to occur in people of Asian heritage.

Finding a match for a bone marrow transplant is nearly impossible. In Alesha’s case, she had a 1 in 19 million chance to find a match; she had better chances of winning the lottery. In other words, every person in Texas would need to take a quick test to see if they would be a match for her. The test entails a quick swab of your cheek with a cotton swab and can be done by following directions in a mail-in kit or at a donor center or even a bone marrow drive.

Salima’s Story

On a Friday evening in Denver Jamatkhana, announcements were read and included plans for a bone marrow registration drive planned by the Aga Khan Social Welfare Board. Salima Dadani was in attendance that night and quickly registered. That evening she had her cheek swabbed and was done within a minute. Truth be told, it was so quick and easy that she had forgotten all about it.

Two and a half years later, Salima received a call that would not only change her life but save Alesha’s. She was asked if she would still be interested in donating her bone marrow and potentially saving a life.

“There was no question in my mind, it was going to happen however and whenever it needed to. I was blessed to be chosen,” Salima said.

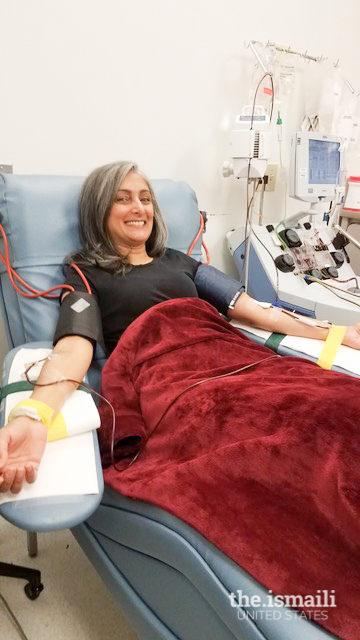

Image 2

Alesha’s blood type and disorder were so rare that cheek swabs weren’t enough; multiple blood draws needed to be done to ascertain whether the match was compatible. Blood samples were drawn and flown to Alesha’s specialists in Texas who conducted a battery of tests and studies on the blood samples.

The stars aligned perfectly through those tests and Salima was given the green light to donate her bone marrow. At this point, she wasn’t given any information about who the donation would be going to, how old the person was, where the patient lived or even the family’s religious beliefs.

Salima was donating her bone marrow or what’s known as a peripheral blood stem cell (PBSC). The process entails collecting blood-forming cells that are found in the bone marrow and in the circulating (peripheral) blood. Collecting the donation is non-surgical and takes place at a blood center or outpatient hospital facility.

For 5 days leading up to the PBSC, Salima had to take injections of a drug to increase the number of blood-forming cells in her bloodstream. While there were potential side effects, she did not experience any.

The morning of the donation, Salima arrived at the hospital at 6:30 a.m., completed some pre-op tests and the blood draw started at 7:30 a.m. The donation entailed having her blood removed through a needle in one arm and passed through a machine that only collected the blood-forming cells, then the remaining blood was returned to her through a needle in the other arm. The process took over eight hours and it was completed by 3 p.m.

After the blood draw, Salima went home to rest and recuperate. “It was exhausting, kind of like having the flu,” she said when speaking about the side effects.

Alesha’s and Salima’s families connect

The blood was flown to Alesha’s hospital and successfully transferred to her body. By the grace of God, her body did not reject the transplant and she would be on her way to recovery. Her family was told that it can take six months to a year after a transplant for her body’s immune system to work as well as it should.

The donor and donee both had the option to remain anonymous. “I was afraid of releasing her information because I was hoping the donor would release his or her information as well,” Mehreen said.

On the flip side, Salima debated about keeping herself anonymous because she didn’t do the donation for recognition. Ultimately, thoughts of her own child lead her to disclose her information. She hoped if her child were ever in a similar situation the donor would do the same.

Both families were elated when they learned they both were open to sharing their information. Salima and Alesha met virtually for the first time in December 2020 and after speaking for a few minutes discovered they were both Ismailis.

Mehreen said, “To know and see someone who gave the gift of life to your only child is overwhelming. She’s our angel.” And Salima added, “It’s funny how complete strangers become family… your family just exponentially grows and there’s just so much love.”

Alesha has been doing well but has encountered other medical issues related to her bout with bone marrow disease. Nevertheless, she is a happy and thriving toddler.

Mehreen and Salima both sincerely hope for those within and outside of the Ismaili community to register to donate. A few minutes of time could save a life someday.

“The donation is the easy part. It’s the recipient who has to do more work,” Salima said.

Resources:

- Be the Match click here

- Register to donate at: click here

- Find a donor registry drive click here