In his work of prose entitled Gulistan (Rose Garden), the 13th Century Persian poet Sa‘di captures the sacredness and connectedness of human beings in the poem entitled, “Bani Adam” (Children of Adam):

The children of Adam are parts of one whole

For they were formed of a single essence.

When one member is hurt by fate, the other members cannot remain at ease.

If you are unconcerned with the troubles of others

You are not fit to be called a human being.1

In these verses Sa‘di speaks to the common core of humanity and the unity of creation that binds every being. If we think about the world in its current state, it would seem that we have not learned from the wise words of Sa‘di. We have yet to overcome our fear of others in order to acknowledge different perspectives and embrace one another.

At present, the most pressing concern for humanity is finding a solution to how we can coexist peacefully and productively, especially under these challenging times of the pandemic. The contemporary world brings with it the benefits of transnational connections and accessible mobility, while also putting forward challenging questions of how we interact with others, and how to embrace differences. We still do not understand differences, and we fear what we do not understand.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has devoted time and energy to address the challenges of living in the present world through his public speeches and the institutions of the Ismaili Imamat. He provides a context-rich approach that brings together religious commitments and ethical considerations, which is based on the inseparability of din (faith) and dunya (world).2

Implicit in the Imam’s guidance is a mixture of prescriptive and applied ethics that carry an overall sensitivity towards the dignity of human beings. An important feature of the Imam’s message is embracing a cosmopolitan ethic. This worldview is premised on the concept of cosmopolitanism (literally “citizen of the world”), which is concerned with people’s multiple belongings and their affiliation to a particular nation, religion, community in relation to shared commitments. The model articulated by the Imam consists of an ethical component that emerges from and is grounded in religious discourse, which affects almost all socio-cultural and political spaces.3 It is an orientation that enables dialogue and partnerships among different peoples in order to advance the quality of life of every person.

The ethical component in the Imam’s message is crucial because ethics relate to everything one does: one’s attitudes, decisions, and actions are based on one’s values and beliefs. The cosmopolitan ethic, described by the Imam, aims to balance faith-based values (particularities of traditions) with a set of diverse ethical norms that bind humanity, which also emerge from faith.

At the core of the Imam’s cosmopolitan worldview is a deep regard for the spiritual; it is informed by key religious precepts. First and foremost, it stems from the belief that humankind is created from a single soul. The Imam has consistently referred to surah An-Nisa, ayah 1, in which Allah says: “O mankind! Be careful of your duty to your Lord, Who created you from a single soul and from it created its mate and from the two spread a multitude of men and women.”4 He has outlined this ayah as a pivotal source of his cosmopolitan spirit that places emphasis on the unity of humankind and underlying human diversity.

Secondly, the Imam’s cosmopolitan ethic is inspired by other Qur’anic verses such as surah al-Hujurat, ayah 13, which states: “O mankind! Truly We created you from a male and female, and We made you peoples and tribes that you may know one another.”5 Taken together, these Qur’anic injunctions should be understood as divinely ordained directives of morality and ethics that encourage Muslims to embrace a common humanity while acknowledging and respecting its diversity. It is about putting faith into action; it’s about engagement and service to humankind. In fact, this verse actively encourages individuals to know one another so that we may extend our love and kindness towards the other. It further inspires us to reflect and give thanks to God for the distinct gifts he has bestowed upon each individual, which can only be appreciated when we genuinely get to know one another.6 The implication is that knowing the other is a fulfillment of the divine will and therefore of being Muslim and indeed of being human.

The Imam’s guidance offers a balanced approach to cosmopolitanism that aims to weave together the universal and the particular, as well as the spiritual and the material.7 The Imam has previously explained:

A cosmopolitan ethic accepts our ultimate moral responsibility to the whole of humanity, rather than absolutizing a presumably exceptional part … [it] will honor both our common humanity and our distinctive identities — each reinforcing the other as part of the same high moral calling.8

There is an inherent recognition of peoples rooted in their own particular identities, coupled with an understanding that a universal cosmopolitan spirit is shared through encounter and engagement with our fellow human beings, and indeed the rest of creation, the custodianship of which has been entrusted to human beings. What emerges from the Imam’s messaging is an appreciation of diversity and a moral compass that beseeches us to find the sacred in one another as well in the rest of creation, for both, as the Qur’an teaches, are the ayāt of Allah. Although the Imam’s perspective is rooted within Islamic discourse, its relevance extends to all contexts that necessitate moral sensibility and human responsibility.

It is evident that the cosmopolitan ethic is inspired by a vision of Divine love that is ethically empowering and all pervasive. It constitutes an internal commitment for ongoing spiritual reflection, which may deepen and refine one’s own ethical sensibilities.

The cosmopolitan ethic as articulated by our Imam is not a passive reality, but a continuous project by which to figure out how to exist amongst others and ourselves without forsaking the particulars that define diverse communities, but are always in flux. As Hazar Imam said, “as we strive for this ideal, we will recognize that ‘the other’ is both ‘present’ and ‘different.’ And we will be able to appreciate this presence – and this difference – as gifts that can enrich our lives.”9

Indeed, this ethical cosmopolitanism requires a vision – a sort of transcendent truth to aspire to – and the Imam offers just that. Taking his vision to heart will allow each one of us to truly engage in knowing one another, seek knowledge of that which we do not understand, and thereby help to re-instill dignity to human kind – one being at a time.

1 This verse is inscribed at the entrance of the United Nations building in New York. The above is a modified translation of Sa‘di’s ‘Bani Adam’ from Eric Ormsby, “Literature” in Amyn B. Sajoo (Ed.), A Companion to Muslim Ethics (London: I.B.Tauris, 2010), pp. 53-78, quote at 69. For original translation refer to Shaykh Mushrifuddin Sa‘di of Shiraz, The Gulistan (Rose Garden) of Sa‘di, trans. Wheeler M. Thackston (Bethesda, MD: Ibex Publishers, 2017 [2008]), p. 22. More recently, the poem was featured as one of Coldplay's songs (also called ‘Bani Adam’) on their album Everyday Life released in November 2019.

2 Karim H. Karim, “Speaking to Post-secular Society: The Aga Khan’s Public Discourse” in Nurjehan Aziz (Ed.), The Relevance of Islamic Identity in Canada: Culture, Politics, and Self. (Toronto: Mawenzi House, 2015), pp. 97-107.

3 Sahir Dewji, “Beyond Muslim Xenophobia and Contemporary Parochialism: Aga Khan IV, the Isma‘ilis, and the Making of a Cosmopolitan Ethic,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Wilfrid Laurier University (2018), pp. 235-293.

4 Syed Hossein Nasr, et al, eds., The Study Qur’an: A New Translation and Commentary (New York: HarperOne, 2015), Q 4:1, p. 189. This verse and many others affirm the divine origins of human diversity and unity; see for example Q 5:48, 11:118, 30:22 and 49:12.

5 Syed Hossein Nasr, et al, eds., The Study Qur’an: A New Translation and Commentary (New York: HarperOne, 2015), Q 49:13, p. 1262.

6 Asma Afsaruddin, “Finding common ground: ‘Mutual knowing,’ Moderation, and the Fostering of Religious Pluralism” in James L. Heft, S.M., Reuven Firestone, and Omid Safi (Eds.), Learned Ignorance: Intellectual Humility among Jews, Christians, and Muslims (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

7 Sahir Dewji, “Shattering Stereotypes With Aga Khan IV and the Ismaili Community”, Fair Observer.

8 Aga Khan IV, “The Cosmopolitan Ethic in a Fragmented World,” Samuel L. and Elizabeth Jodidi Lecture Series (Cambridge, Massachusetts, November 12, 2015). Weatherhead Center for International Affairs Harvard University website Click here

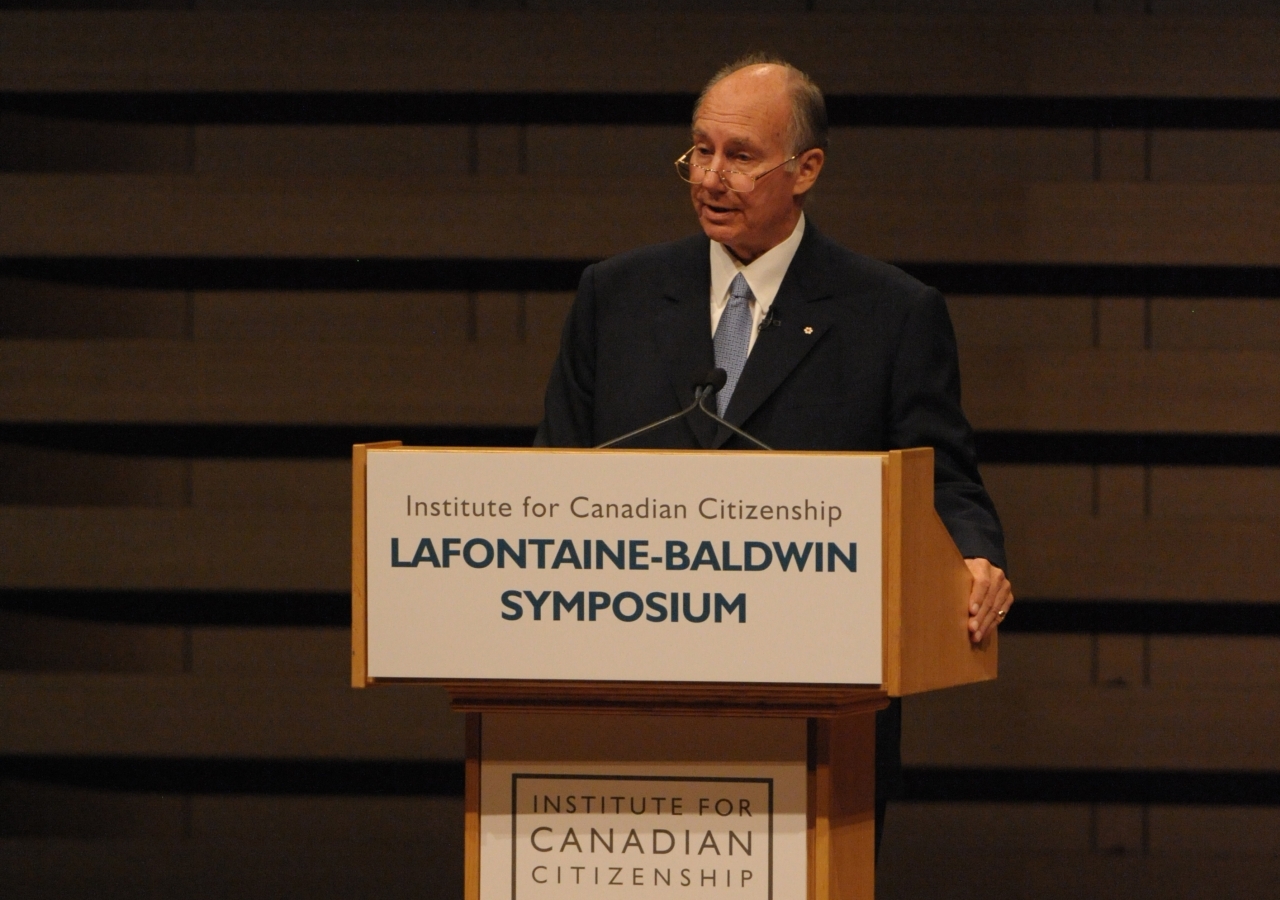

9 Aga Khan IV, “10th Annual LaFontaine-Baldwin Lecture” (Toronto, Ontario, October 15, 2010), Aga Khan Development Network website Click Here