The followers of Imam Muhammad b. Isma‘il, the Isma‘ili Shi‘ia, lived in very perilous circumstances in various localities. By the middle of the 9th century, the Imams had settled in Salamiyya in Syria. During this period, they concealed their identity from the public and sought to consolidate and organize the widely dispersed Ismaili community. The scholars and local leaders of the Ismailis, known as da‘is or ‘summoners’, maintained contact with the Imams and organized themselves into a da‘wa, a network of shared commitment to the Imam and intellectual values. When they emerged into the public limelight at the beginning of the 10th century, the Ismaili community was remarkably well organized and cohesive.

The Ismaili da‘is sought to extend their influence and forge alliances to create the foundations of an Ismaili state under the rule of the Imam. The opportunity of laying the foundations for a state gained momentum at the beginning of the 10th century, when the Ismaili Imam of the Time, ‘Abdallah, moved from Syria to North Africa. In 910 CE, he was proclaimed Amir al-Mu’minin (‘Commander of the Believers’), with the title of al-Mahdi (‘The Guided One’, equivalent to the idea of ‘The Saviour’). The dynasty of the Ismaili Imams, who for more than two centuries reigned over an extensive empire centered in Egypt, adopted the title of al-Fatimiyyun (commonly known as the Fatimids), after Fatima - Prophet Muhammad’s daughter and the wife of Imam ‘Ali, from whom the Ismaili Imams descended. The proclamation of Imam ‘Abdallah al-Mahdi as the first Fatimid Caliph marked the beginning of the Ismaili attempt to give a concrete shape to their vision of Shi‘i Islam.

The Fatimid period represented the ‘golden age’ of Ismaili Shi‘ism, when the Ismailis possessed a state of their own, and Ismaili scholarship and literature attained their summit. The Fatimids expanded their influence and authority, from their initial base in the present-day Tunisia, advancing to Egypt during the reign of the fourth Fatimid Imam and Caliph, Al-Mu‘izz. In 973 CE, Imam-Caliph al-Mu‘izz transferred the Fatimid capital from North Africa to the new city of al-Qahira (Cairo), which was founded by the Fatimids in 969 CE. Henceforth, Cairo became the centre of a flourishing empire, which at its peak extended westward to North Africa, Sicily, and other Mediterranean locations, and eastward to Palestine, Syria, Yemen, and Hijaz with the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

The founding of the Fatimid caliphate also provided the opportunity to spread the Ismaili Shi‘i da‘wa. The religio-political messages of the Ismaili da‘wa were disseminated by networks of da‘is within the Fatimid dominions as well as in other regions. The Fatimid da‘wa activities reached their peak in the long reign of Imam al-Mustansir Bi’llah. The da‘is successfully converted many in Iraq, Persia, Central and South Asia, as well as in Yemen. Some of the most eminent da‘is and scholars of the Fatimid da‘wa were: Abu Ya‘qub al-Sijistani, al-Qadi al-Nu‘man, Hamid al-Din al-Kirmani, al-Mu’ayyad fi’l-Din al-Shirazi and Nasir-i Khusraw.

In the last decade of the 11th century, the Ismaili da‘wa witnessed a schism over the question of succession to the Imam and Caliph al-Mustansir Bi’llah (d.1094 CE). One section of the Ismaili communities of Egypt, Yemen and western India recognized his younger son al-Musta‘li, who had succeeded to the Fatimid throne as the next caliph. The other faction based in Persia, under the leadership of Hasan-i Sabbah supported al-Mustansir’s elder son and designated heir, Nizar, as the rightful Imam. The Nizari Ismaili Imams of modern times, known under their hereditary title of the Aga Khan, trace their descent to Imam Nizar. Today, the two Ismaili branches are known as the Musta‘li and Nizari, named after al-Mustansir’s sons who claimed his heritage.

The Nizari Ismailis

The seat of the Nizari Imamat was originally established in Iran, where the Ismailis had already succeeded, under the leadership of Hasan-i Sabbah, in founding a state comprised of a network of fortified settlements, with its headquarters at Alamut, in northern Iran. The Nizari state later extended to parts of Syria. However, rivalries among Muslims over issues of power and territory continued in medieval times. In particular, the Nizaris were obliged to struggle against the Saljuq Turks and other adversaries that threatened their existence.

It was within this context of debilitating warfare among Muslims, shifting alliances and the rising Mongol threat that the Nizari Ismaili Imam Jalal al-Din Hasan (d. 1210-1221 CE), who ruled from Alamut, embarked on a policy of rapprochement with Sunni rulers. The Sunnis reciprocated positively, and the Abbasid Caliph al-Nasir acknowledged the legitimacy of the Ismaili Imam’s rule over a territorial state. Imam Jalal al-Din’s policy - similar to his Fatimid forebears - was a practical affirmation that whilst differences in the interpretation of the Islamic message existed among Muslims, what mattered most were the overarching principles that united them all.

The Ismaili state centered at Alamut, was uprooted by the Mongols in 1256 CE. Subsequently, many Nizari Ismaili groups found refuge in Afghanistan, Central Asia, China, and the Indian subcontinent, where large Ismaili settlements already existed. The centralized da‘wa organisation and direct leadership of the Nizari Imams disappeared for a while with the fall of the Ismaili state. Under these circumstances, scattered Nizari communities developed independently, following the leadership of local dynasties of da‘is, pirs, and mirs, while resorting to the strict observance of taqiyya (dissimulation) and adopting different external guises. For example, given the esoteric nature of the Ismaili tradition, the Ismailis who remained in Iran disguised their identity under the cover of sufism to escape persecution.

This practice gained wide currency also among the Nizari Ismailis of Central Asia, to the extent that the Ismaili Imams appeared to outsiders as Sufi masters starting with Imam Mustansir bi’llah II (d.558/1480), who carried the Sufi name of Shah Qalandar. However, in the 14th century, new centers of Nizari activity were established in the Indian subcontinent, Afghanistan, the mountainous regions of Hindukush, Central Asia, and parts of China. In South Asia, the Nizari Ismailis became known as Khojas, and they developed a distinctive devotional literature known as the ginans.

The Modern Phase

The modern phase of Nizari Ismaili history, as with other Muslims, can be dated to the 19th century. As a result of political turmoils in Iran during the 1840s, the 46th Nizari Ismaili Imam, Hasan ‘Ali Shah, migrated to India. He was the first Nizari Imam to bear the title of the Aga Khan, which was granted to him by the Persian monarch Fath ‘Ali Shah Qajar. His leadership enabled the community in India to lay the foundations for institutional and social developments and also fostered more regular contacts with Ismaili communities in other parts of the world. After his death in 1881, he was succeeded by his son Imam ‘Ali Shah, Aga Khan II, who continued to build on the institutions created by his father, with a particular emphasis on providing modern education for the community. He also played an important role in representing Muslims in the emerging political institutions under British rule in India.

Following his early death in 1885, Aga Khan II was succeeded by his eight-year old son, Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah, Aga Khan III. Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah reigned as Imam for seventy-two years - the longest in Ismaili history - and his life spanned dramatic political, social and economic transformations. His long-term involvement in international affairs, his advocacy of Muslim interests in troubled times, and his commitment to the advancement of education, particularly for Muslim women, reflect some of his significant achievements. It was under his leadership as Imam that the Nizari Ismailis were transformed into a progressive community, enabling them to adapt successfully to the challenges of the 20th century.

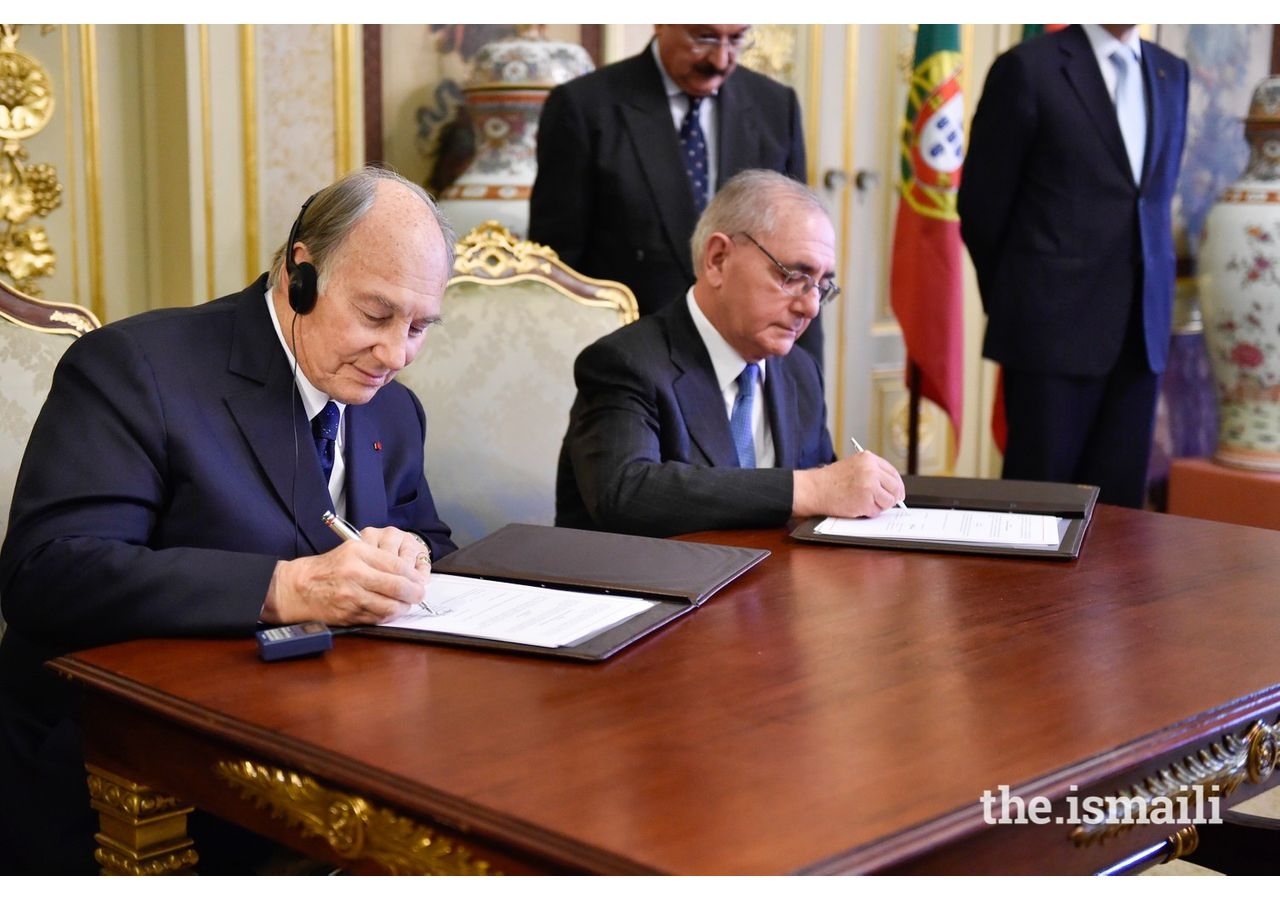

Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah was succeeded by his grandson Shah Karim al-Husayni, in 1957, as the forty-ninth Imam of the Nizari Ismaili community, who has substantially expanded the modernization policies of his grandfather. Indeed, he has created a complex institutional network, referred to as the Aga Khan Development Network (AKDN), which implements numerous projects in a variety of social, economic and cultural domains.

Mawlana Hazar Imam has been particularly concerned with the education of Ismailis and Muslims in general. In the field of higher education, his major initiatives include: The Institute of Ismaili Studies, founded in London in 1977 for the promotion of general Islamic as well as Shi‘i and Ismaili studies, and the Aga Khan University in Pakistan and Africa, with faculties in medicine, nursing and education, as well as its Institute for the Study of Muslim Civilizations, based in London. In 2000, he founded the University of Central Asia with campuses in Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan, which aim to address the specific educational needs of the region's mountain-based societies. Mawlana Hazar Imam takes a personal interest in the operations of all his institutions, and activities.

Numbering more than ten million, today the Nizari Ismaili heritage includes cultural contributions of the Ismailis of Central Asia, South Asia, Iran and the Arab Middle East. During the 19th and 20th centuries, many Ismailis from South Asia migrated to Africa and settled there. In more recent times, Ismailis have also migrated to North America, Europe and Asia Pacific countries. However, despite such a diversity of ethnicity and cultures, the shared values that unite Nizari Ismailis are centered on their allegiance to a living Imam. The guidance and the efforts of the Ismaili Imam have enabled the Ismaili community to emerge as progressive Shi‘i Muslims in more than twenty-five countries around the world, where they generally enjoy exemplary standards of living while retaining their distinctive religious identity.