Following Mawlana Hazar Imam's lecture at the LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium in October 2010, Sheherazade Hirji of The Ismaili Canada magazine met with former Governor General of Canada the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson and Mr John Ralston Saul to discuss the lecture series, and the work of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship.

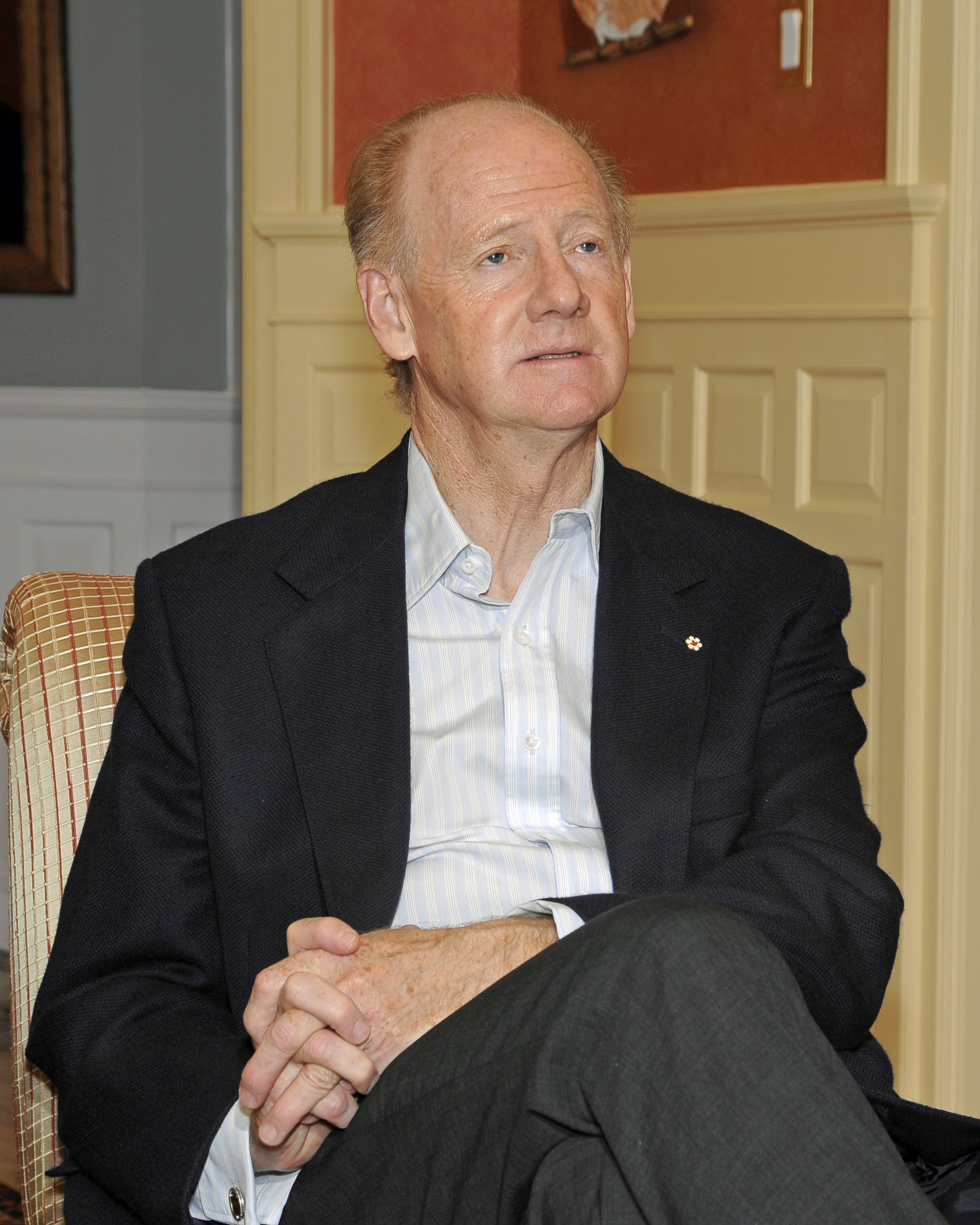

Former Governor General of Canada the Right Honourable Adrienne Clarkson and John Ralston Saul spoke with Sheherazade Hirji following Mawlana Hazar Imam's lecture at the 2010 LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium. Moez Visram

The Ismaili Canada (IC): This is the 10th anniversary of the LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium. What were you hoping to accomplish in the 10th anniversary? And how did His Highness' speech contribute towards achieving your objectives?

John Ralston Saul (JRS): Well, we started the LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium in the fall of 1999. I did the first one in 2000, literally 50 yards away from where His Highness gave the 10th anniversary lecture. The idea was to launch a whole different kind of debate on the public good and to use as the basis for that, the people who invented the idea of the public good in Canada. Increasingly, we realsed that they put out an idea that was so strange for its time, that it was amazing that they were so successful. Over the last nine lectures, speakers have included two Aboriginal leaders, the Chief Justice, and Adrienne, of course. We wanted the 10th to be both national and international and we wanted somebody who was an absolutely convincing voice about pluralism and diversity as we understand it. And who has many years of experience, not simply advocating but understanding what can be done, what is difficult to do, how it can function in the world and what are the risks of not doing it? What are the opportunities if it does happen? And frankly, when you make the list of people who can do that, it's a very short list. In fact, there's just about one person on it.

Adrienne Clarkson (AC): Yes, His Highness the Aga Khan. He's unique in the world in that he is a spiritual leader, he is a leader of some 14 million Ismailis in the world, and he is also the head of the largest non-governmental organisation in the world. And he is a businessman. So he has all of these qualities within him. He bridges the East and the West. I think that made it possible for him to understand exactly what LaFontaine and Baldwin stand for in Canada. So for 10 years we've had very interesting Canadians. To have somebody like His Highness who, in the world, represents something extraordinary, is a wonderful step forward for us because of the message of LaFontaine and Baldwin – that you have responsible government, that democracy works if people are involved in the common good – that is a Canadian message that can be brought into the world. His Highness understands that and knows that it is meaningful. I think there's been a message through all the LaFontaine-Baldwin speeches, which is that we are looking always not from a basis of what we believe in, which is democracy, but we are looking forward to making a world in which those principles are held as a given, and we expand it. I think His Highness is expanding our LaFontaine-Baldwin idea into the world for us. And sometimes we're so short-sighted in looking at the history of immigration. We think of some of the sadder parts of the 20th century when Canada didn't behave very well in terms of accepting immigrants but we forget that LaFontaine, in the 1840s, made a wonderful speech to his electors about how we will accept immigrants who will come to this country: “We don't know who they will be yet but they will become Canadian as we are Canadian.” And of course, that ideal has come into play now, because “as we are Canadian”, is not the same “as we are American.”

IC: Let's talk about the discourse around multiculturalism and its relationship to pluralism. From where we started in the 1840s, towards a state-supported policy of multiculturalism in the 1970s, and now this sense of living together actively in the notion of pluralism. Are these different discourses or are they part of the same conversation?

AC: I don't think they're different discourses. They're a perfectly logical evolution of each other, the difference now is that it is something that we value and are interested in. We didn't before. In the initial stages, people want to fit in and want to know all the rules. Now, we see the strengths in the different traditions that we've brought to each other, and that's the stage that we are at.

JRS: The phrase I always use is that Canada functions as a multiple personality order. But what is fascinating is that it was already happening in the 16th, 17th, 18th century here and a lot of that goes back to the Aboriginal approach towards welcoming and adopting people into circles. I wrote about this in the Fair Country. The Aboriginal approach towards citizenship, which is not a word they would have used, was not race-based. There was no concept of race in Aboriginal civilisation. There were concepts of family and community and geography and place. It was the Europeans who insisted on the concept of race and defining by race in the treaties and in the Indian Act. But what they were saying was, “Oh, you're here. Ah, well, if we're not going to fight you, then you have to be part of our family and our community so here's how we're going to adopt you into our circle.” What it means is that now you're in the family, you have the obligations of a mother. A mother sits down beside elders and everybody has a different role and the role of the mother is to ensure that everybody looks after everybody else. The LaFontaine-Baldwin idea clearly saw that the European system didn't work and therefore they had to come up with a different system. So the immigration and citizenship policies of Canada were, in a sense, produced out of that failure by the reform movement. The first bill they put through when they came into power was a bill to regularise immigration and the fair treatment of immigrants as they were naturalised into citizens. You can draw a line from there to the 1970s.

JRS: And what I think people have found very confusing is that every 20, 30, 40 years, we have a new wave, generation, of immigration and so, yes, in the 70s, you could say we opened up to “non-white”, as the Europeans would say. But if you go back to the 1890s, you actually find bigger per capita immigration than today, and in fact, at certain points, bigger in raw numbers than today. They were taking some 400 000 people a year. There were Ukrainians and Jews from central Europe and Swedes, Poles, Russians and Icelanders. And there's another chapter, of course, the Chinese, the Sikhs and the Japanese. Each one of these is, a chapter, but they're all related. We do ourselves a disservice if we think that it all started in the 1970s because then we don't understand where it comes from. It is like chapter 6 or 7 in a battle of inclusion and egalitarianism, which we keep forgetting and then remember. The point about the link between LaFontaine and Baldwin and His Highness's speech is that it links 170 years of immigration, integration, pluralism, diversity, egalitarianism. It's a very important linking.

IC: Let's explore pluralism and citizenship. We live in a world where people are global citizens. They hold multiple citizenships and move easily across identities, communities. What does that mean for the context of citizenship, or for Canadian citizenship?

AC: I think that the context is very valuable for Canadian citizenship because of what we believe in as citizens. We live as citizens in a country where we have democracy and where we make very sophisticated choices by the world's standards. We're very fortunate because we have the infrastructure of law and of a long history of democratic voting and a parliamentary system that works, that we have that possibility of bringing that in us as individuals to whatever parts of the world that we're a part of. And that is I think an extremely valuable thing. It isn't just a passport or a piece of paper. I would risk saying that people who say, “well it's really just a handy kind of thing to have because it's a valuable passport and everyone thinks Canadians are okay,” that even that kind of debasing of it is, in a way, a value of saying, “we know that this is an important kind of thing to have because Canadians do believe in certain things,” and every person who carries a Canadian passport or is a citizen carries those values implicit in what it is to be a Canadian citizen. We just take for granted in many ways that those freedoms are ours but we don't often in a big city, places like Toronto, Vancouver, Montreal appreciate that. I've just come back from the interior of BC and the largest city there is 10 000 people and most of them are 3–, 4–, 5 000 population. There, you sense that what we have as a country is so dense and complex. It's very difficult to understand but I think people who are caught up in a life where they think, “oh well, Toronto isn't that much different from living in London or in Paris, it's just another big city in many ways with elements of different kinds of sophistication in different languages,” but in fact, the identity between us in a city like Toronto and people living in smaller centres like Brandon, Manitoba or Red Deer, Alberta is a strong link. It is something that people who've come here as immigrants understand instinctively about being Canadian. It doesn't matter what their original culture is and what they hang on to, they get it.

Take as an example, Naheed Nenshi. It's, to me, no surprise that we would have a 38-year-old Ismaili mayor of Calgary. We met him 10 years ago and he was already terribly involved with his city, with his generation of people, with the problems that he could see happening with his own background, which is highly sophisticated and international. This kind of person grows out of what we have in this country.

John Ralston Saul greets a participant at the roundtable discussion that followed the LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium. Courtesy of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship

JRS: I think one has to be really, really careful. First of all, most people changing countries are not international. Those of us who have university degrees and PhDs and work for big organisations think of it as international. 80% of the people who are changing countries are actually desperate to get somewhere to settle down in a very old fashioned way. They want to be somewhere and they're going to stay there. If you look at the number of people coming to Canada, the vast majority of them are coming out of a courageous desire to find a place to live. So that idea that we're all moving around the world is an elite idea, it never comes from people who've arrived here with nothing.

AC: I count myself among these people because I arrived here with nothing. I would say 80% of the people who come, don't come by choice. We came somewhere where we were not going to starve or be killed. I think we would have come even if they'd said to us: “Maybe if you come you won't be able to vote because – or for a while you won't be able to or maybe you won't be able to get this education.” We would have come anyway because at least we would be alive and where there is life, there is hope.

IC: The theme of what you are saying suggests the notion of multiple cultural competencies. Is this what Canada has built, the ability to move from conversation to conversation with different people and different backgrounds?

JRS: It's the multiple personality order. And we're relaxed about it.

AC: And it's what His Highness talked about as the cosmopolitan ethic. That was a wonderful phrase.

JRS: It means you have to have confidence in the citizen. The loyalty of the citizen is not defined by the state. The loyalty of the citizen is defined by the citizens. They are the source of legitimacy of the state. And that's the difference.

If you understand that what's interesting about Canada and Canadian citizenship at its best, is that these ideas of inclusion and egalitarianism and multiple personality order and how people live together. What is the Canadian model for people living together and how is that philosophically, emotionally, ethically, spiritually a different model, a fundamentally different model from the model put forward in the classic western monolithic nation state? If you don't understand that, then you're in deep trouble. Because then, you're not helping those citizens who are travelling or settling, going back home and say: “Well listen, this is why Canada's interesting or this is what we do or here's another way of doing it. You don't need to divide Cyprus in two. It's entirely possible for us to live together.” Or: “You know, we don't need to kill each other over our religions because here's a whole other approach. You don't lose your religion because you're living with people of other religions. Here's how we do it in Canada.”

And that is what we're talking about, LaFontaine and Baldwin are talking about, and that's what His Highness the Aga Khan brought to the forefront with his deciphering and laying out of how pluralism works.

IC: Let's talk about the Institute for Canadian Citizenship which is trying to animate this notion of active citizenship. I think about members of the Ismaili community, for example. How can we animate this sense of citizenship?

Adrienne Clarkson engages in a discussion on Canadian citizenship with participants at the roundtable that followed the LaFontaine-Baldwin Symposium. Courtesy of the Institute for Canadian Citizenship

AC: Well, I think Ismailis, of all people, because of having been a diaspora, understand it better than most. Really, when you have been displaced and moved from place to place, it is sometimes for a couple of hundred years but still, you are on the move, you pick up things in each place that you go to, and you splinter out a little. I'm a child of the Chinese diaspora all over Asia and so there are histories of people who have that. The Ismailis are a group of people who have moved and been moved from place to place because they've had to make their way when they had the rug was pulled out from under them, literally. What's happened among the Ismailis is that they have developed this strong sense of giving back and of doing things for others, which I think dovetails very much with the Canadian way of life. All the people who heard His Highness at the Symposium, said what he said was remarkable but also there was a thread of spirituality going through what he said, that there was a feeling of faith. We have that image of the Ismailis – everybody knows now or is starting to know and they certainly will get a big boost of knowing it with Naheed as mayor of Calgary – that the Ismailis give back.

That is something that is expected of them culturally and not just religiously. The two things are intertwined. There is this tendency among established Canadians who've been here a long time to assume that people coming from all over the world have nothing and we have everything. That is not true.

JRS: We see that in the roundtables we do at the citizenship ceremonies we organise. Very interesting ideas come from new citizens around the tables. One is a sort of enlightenment-driven discussion in western democracies around separation of church and state and this confusion – it's both necessary, because of course, they're dealing with cases where the churches were standing in the way of democracy and they were what they were, for better and worse. But there's a whole other way of looking at this which I thought came out beautifully in His Highness' speech, which is this idea that spirituality inhabits everything that we do. It isn't necessarily about the church and the state; it's actually about the spirituality of our actions, and that the spirituality inhabits us. It isn't about power; it's about ethics; it's about morality; it's about social awareness; it's about responsibility to the other. And the fascinating thing is that it actually joins directly to the original ideas of belonging in Canada, which are the Aboriginal ideas. There's this ongoing confusion and discussions between Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals, particularly at the state level, where Aboriginals are always talking about spirituality and people would say, “but wait a minute, we don't want to have the church, it's the state.” They're not talking about that; they're saying that if you're going to look after the environment, you have to come at it with an integrated spiritual approach, which then will turn into politics, which will turn into environmental policy. Or your inclusion of others comes out of the integrated nature of spirituality. So I thought that what His Highness was saying links very nicely with the roots of, if you like, ethics and the inclusion of the public good at its best in Canada.

The ICC is an organisation with programmes. Behind the programmes lie these ideas, these 400-year-old ideas in Canada of inclusion which are being reinvented every day, and so how do you ingest these sort of contemporary concepts of, say, spirituality and inclusion and egalitarianism and pluralism into an old idea of inclusion and spirituality? And so you do that through your programmes. We already have many Ismailis involved with the ICC on volunteer committees across the country.

Our citizenship ceremonies include a one-hour roundtable discussion on citizenship. Having the Ismaili voice in there as citizens is very important because they bring an understanding often of what it is that we're trying to do. But with those volunteer committees, our idea was that they'd start organising the ceremonies but they would quickly expand into working with new citizens, developing local programming. We have a competition on best practices this year. So there's this fabulous idea, how do you spread it across the country?

Well, you give it a prize, you put it into Macleans magazine.

AC: I think really what's interesting is that by having His Highness give this speech and talk about plurality, it causes us to look at Islam in Canada in a different way. Because of total ignorance and often wilful ignorance in the western world, Islam is thought of as one religion but it is just as varied in every possible way as Christianity or Judeo-Christianity.

JRS: The ICC is not there yet but I think we will get there because it's a big question. The educational system in this country does not reflect the reality of the country. It literally doesn't reflect who's here, that's a utilitarian interpretation of the problem, what's more important is that it reflects a European approach towards a monolithic society. It doesn't reflect our ancient 19th century and contemporary idea of what a society, which is this multiple personality order. We have to invent something deeply different here and then we have to be able to explain ourselves to ourselves, but also explain ourselves to the world, and here we're failing in that we have not given ourselves the tools, the language, the ideas to talk about it. The Aga Khan has just contributed something enormous because he's given, as we hoped he would, a breakdown of how pluralism works, that can be explained anywhere in the world. So he made an enormous contribution with his speech to that discourse, much more than the universities have been giving quite frankly, to say nothing of politicians and civil servants. Really an interesting breakthrough in terms of a committed view. This is what pluralism is. Here's the history. Here's how it functions. Here's some structures. Here's how to talk about it. So I think that we have to go outside of Canada and talk about this other approach.

I think Ismailis could play a very important role around the world in this sort of internationalising of a Canadian argument, which doesn't belong to us but we are perhaps one of the leading exponents of it and have been for 150, 160 years, with embarrassing down days and wonderful up days.

So, carrying this, not simply into our own consciousness, but into the consciousness of the world so that when somebody in Europe says, “multiculturalism has failed” we cannot simply say: “Well you're actually not talking about multiculturalism. You don't understand what multiculturalism is.” You know, bringing in cheap workers, putting them in isolated ghettoes, not giving them citizenship and then saying it didn't work out. You have to be able to explain it and I think Ismailis have a big role to play, a very important role at the international level. They are already doing it, look at the Aga Khan University in Pakistan.

IC: What a wonderful aspiration, because we could also bring other communities into this conversation to do what you're doing with the institute which is planting trees under whose shades we will never sit. This is really generational work that takes a very long time.

JRS: And you can do generational work. If you understand that you're part of a process that began before the Europeans were here and that was really formalised in its contemporary form, in the 17th century and each 30, 40, 50 years we get a new idea of how to expand it further. We're sitting under trees if we're paying attention and don't cut them all down and we're planting more trees.

IC: You've been very generous with your time.

JRS: Thank you.

AC: Thank you. We've enjoyed it very much.

Adapted from its original publication in the December 2010 edition of The Ismaili Canada magazine. Learn more about the Institute for Canadian Citizenship at www.icc-icc.ca.