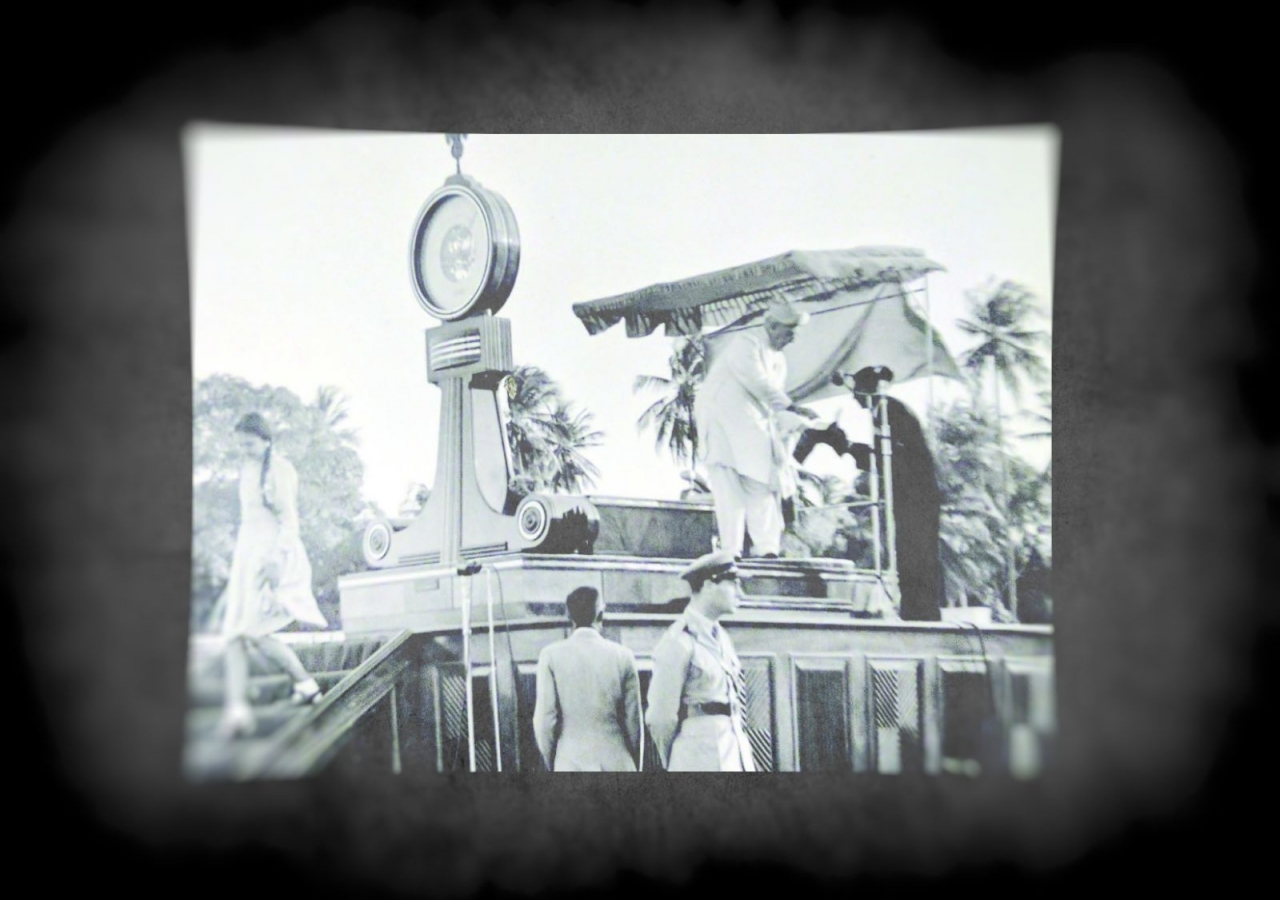

When Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah celebrated his Diamond Jubilee in 1946, darbars were held in two locations – Bombay (now Mumbai), India, and Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania).

For those present, the most vivid memory is of the Imam being weighed as caskets of diamonds were placed on the scale. These diamonds were later used to fund the establishment of major institutions to improve the Jamat’s quality of life. Malek Jiwani, who attended the Dar es Salaam darbar, also remembers the Imam bestowing Begum Om Habibeh with the title of Mata Salamat.

Those who were in attendance, though young at the time, recall the journeys they took to Bombay and Dar es Salaam, and the incredible organization it took to manage the crowds.

Rehmet Meru remembers the Ismailis in her hometown of Gwadar, Pakistan, receiving a telegram from Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah, inviting them to Bombay for the darbar. Meru, now 87, was 16 at the time.

“It took us three days from Gwadar to Karachi,” she says, explaining that the first leg of the trip was done by sailboat. “Nowadays, by car, it takes eight hours only.” The second part of the trip was in a large ship from Karachi to Bombay.

Hassanali Rajwani, now 80, recalls the fanfare around the Bombay jubilee, especially the sargas – Gujerati for parade – the day before. “There were elephants, horses, camels, so many things. So many people on the streets. It was too much fun,” he says.

Rajwani, who was a nine-year-old running around providing ice-cold water to attendees, can’t forget the images of the Ismaili volunteers in uniform, looking as if they were in the military.

Nizar Sultan’s family attended the Dar es Salaam darbar. Only six at the time, he remembers watching the train pulling into Dodoma station with Ismaili flags on both sides of the locomotive. “That is something that is etched in my mind – the pride I felt, the emotions of looking at the flags flying.”

The Ismaili Council had chartered the entire train to take people from Kigoma to Dar es Salaam. Sultan recalls that in order to maximize capacity, the regular first- and second-class cabins, which contained beds, had all been converted into third-class cabins, containing benches only.

Habib Kassam, then 14 and a member of the Boy Scouts, took the train from Tabora to Dar with his family. He fondly recounts how Scouts and volunteers, including himself, were put in the bogi – a cabin with no windows or seats, designated for cargo only.

Eighty-year-old Sadru Allana also remembers travelling from Tabora to Dar es Salaam by train. “I remember my father was a volunteer and was picking up passengers from the train station and transporting them to the campsite.”

The atmosphere on the trains was unforgettable too, as everyone celebrated in anticipation.

On the train from Kisumu to Mombasa, Gulzar Mohamed, 85, remembers khamosh was called over loudspeakers at 7 p.m., followed by prayers. The train’s passengers sang geets all night long and nobody slept. At each stop, the travellers would jump on to the platform to play rasda.

Once in the darbar cities, most non-locals stayed in camp grounds that were “another miracle” pulled off by the Ismailis, according to Sultan.

With 100,000 Ismailis in Bombay for the Jubilee and another 70,000 in Dar es Salaam, tents fashioned of gunnysacks and cardboard provided shelter to many, and the large camp grounds were sectioned off into numbered ‘camps’ in order to organize them. Families were allocated space, which they separated from others’ using their luggage trunks. Then a truck filled with foam mattresses made its way around, providing bedding based on each family’s size.

Sultan and other children were given cards displaying their names and camp numbers to wear around their necks. Still, coming from a town where there were only 1,000 Ismailis, he remembers being overwhelmed by the crowds and being constantly afraid of being separated from his family.

One memory that sticks in his mind is of meal times at the camp sites. On behalf of several families, one representative would collect a large circular tray of food about five feet in diameter. Then they’d all sit around the thali, eating and talking.

Kassam has his own take on the camp grounds: “It was like we were in Ismaili town,” he says. He remembers going around to the different camp sites to meet people with his friends as a fourteen-year-old.

Kassam also mentions the many Qurbani volunteers – those who happily sacrificed the chance to watch Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah’s weighing ceremony for others. He remembers how some women stayed behind to watch young children so the mothers could attend the darbar and the crowd wouldn’t be disturbed.

“Seeing all of our Ismailis together – lots of Ismailis in one place, and always so happy – made me emotional,” Kassam adds. “No one complained.”

Abdul Rahim Rajwani, who was also 14 at the time, did not attend the darbar in Bombay because he decided to be a Qurbani volunteer who helped out with people with disabilities staying in the camps. Another person who didn’t attend the Bombay darbar was nine-year-old Akbar Ali Damani. “We lived in Hyderabad,” he explains. “There were seven people in my family, so only two went to the darbar. This is the biggest difference between the darbar then and now [in Canada].”

Dolat Harji, 92, was one of the mothers who left her baby with the volunteers for over three hours. Harji has one particular memory from Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah’s darbar that still influences her today. On his way out of the hall, the Imam stopped in front of her and asked if she was happy. When she answered yes, he told her she should be happy forever.

“From that day up to now, I’m always happy,” she says. “Whatever happens, I’m happy.”

During the Jubilee, Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah matched Girl Guides and Boy Scouts and divorcees and widows to be married, says Daulat Ramji. Now 81, she also remembers watching the modern looking women from Kenya and South Africa wearing scarves and holding binoculars.

“I was very young but all I can say is I consider myself and all who witnessed Imam Sultan Mahomed Shah’s Diamond Jubilee the luckiest people on earth,” said Ramji.

Speaking on behalf of those who attended the 1946 Diamond Jubilee, Habib Kassam is eagerly anticipating seeing his second Diamond Jubilee: “I never thought I would be so blessed. I am excited again!”

For more articles, please go to the Ismaili Canada Summer 2017 edition online.