Recently, Sahil Badruddin, an interview host for OnFaith (onfaith.co), sat down with Dr. Eboo Patel – Founder & Executive Director of the Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC) and a previous member of President Barack Obama's inaugural Advisory Council on Faith-Based Neighborhood Partnerships – to discuss his insights on contemporary issues such as Interfaith Leadership, Dialogue and Action, Pluralism, Intellectual Diversity, Partnerships, Faith Leadership, and his vision for the future.

Sahil Badruddin: Eboo, thank you for sharing your insights with OnFaith. We're glad to have you with us.

Eboo Patel: My pleasure. Thank you so much for inviting me.

Sahil: Most of us are aware of the concept of interfaith dialogue focusing on bridging divides between people of various faiths, in the hope that conversations will mitigate misunderstandings. However, as the Founder and Director of the Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC), you often emphasize Interfaith Action -- where individuals of different backgrounds can come and work together putting their shared values into action.

Could you speak about Interfaith Action and the power it has in your experience to make a tremendous difference, and increase connectivity between various faiths?

Eboo: Absolutely. Action is another form of dialogue. And in my experience, it is a language of connecting across faith traditions that is especially resonant within those faith traditions, which is to say that Christianity, Hinduism, Islam, etc., they all call on us to speak our faith through action, and it's a language that's especially relevant to young people. For young people who want to engage in interfaith engagement, the language of action, I think is the most relevant useful, constructive, and inspiring language.

Sahil: That’s good to hear. Religions often share similar values as you mentioned, such as compassion, mercy, love, generosity, for example. While religious people are able to draw on these shared values to work together, where do non-religious, non-affiliated, or even secular humanists draw their values from? Because you’ve mentioned that the IFYC works with these groups as well, so could you share your experience?

Eboo: There's a variety of traditions that are not religious traditions. That hold similar values…people like A. Philip Randolph would call themselves secular humanists who were deeply engaged in social action for the common good. So a lot of what IFYC does is identifies heroes or exemplary figures from a range of traditions, very much including non-religious traditions that would highlight the shared values of mercy, compassion, hospitality, etc..

Sahil: Given your message around the urgency of interfaith leadership, you say and I'm paraphrasing – interaction between religious people who orient differently can become a few things. They can become bubbles of isolation, barriers of division, bludgeons of domination, bombs of destruction, or bridges of cooperation. But here is the crazy obvious thing. Bridges don't fall from the sky, nor do they rise from the ground. People built them.

So what, in your opinion, are the top two or three challenges, whether it be administrative, social, societal, intellectual, political, or any other areas you feel that the world faces, today, that negates or overwhelms the spread of more interfaith efforts around the world?

Eboo: I think that there are two reasons that a set of people are suspicious of interfaith work. One is, there's a set of people who view this, as I like to say, as an afternoon coffee issue, but not a morning coffee issue. By that I mean afternoon coffee is something that is nice to have, but morning coffee, a lot of people think is a need to have, and I think part of the goal of the Interfaith Youth Core is to spread the message that interfaith cooperation is actually a morning coffee issue.

It's a need to have issue, that’s a top five priority. I think a second reason that some people are…look [suspicious of] interfaith work is…[based on] some version of a purity test. They say…basically they only want to work with people who are different in the way that -- with differences that they like. And as they like to point out, diversity is not just the differences you like, there are also the differences you don't like, and a very important part of interfaith cooperation is working with people who have views that you actually don't really like.

I think that there are limits to that, but I don't think the limit can be 50% of the population of a country. As I have taken a say, I'm not going to buy a cookie from the KKK Bake sale, but I'm certainly going to engage with somebody who voted differently than I did because otherwise, I'm not really engaged in diversity work.

Sahil: Interesting. For these challenges, any suggestions or even direction you would offer as to how the world can address them in innovative ways, not tried before?

Eboo: I think a lot of these things have been tried before, and one of the things we like to point out at Interfaith Youth Core is that we stand up on the shoulders of giants which is to say that…we frequently look into history at the work of people we admire and find things in those moments of history that we can follow ourselves.

One thing that I would say to [your audience] is to think times in your life when you have found yourself enriched or inspired or cooperating with somebody who had a viewpoint that you just really disagree with. Maybe it was a lab partner in a science experiment. Maybe it was somebody at a science contest. Maybe it was a teacher, but I think, thinking at our own lives, when have we found ourselves enriched or inspired or cooperating with somebody who we disagree with…can help us recognize that this is possible and that, if we think about it in the right way, we can actually increase the numbers and types of circumstances in which we cooperate in that way.

Sahil: You often mention, and you make a case that a good model for effectiveness for interfaith cooperation is the Interfaith Triangle -- attitudes, relationships, and knowledge. Facilitating positive meaningful relationships and advancing appreciative knowledge in combination improves people's attitudes.

You cite Putnam's book, American Grace, in which he argues that if individuals have more positive interactions with, or even more knowledge, of certain religious groups their attitudes actually improve towards them. In fact, attitudes improve towards all religious groups in general.

So how can up and coming interfaith leaders better utilize and scale this model, that is to use, better use the interfaith triangle?

Eboo: It's a great question. I think, keeping the interfaith triangle in mind is a very useful tool and using it as a quick evaluation is also useful. Design an activity in which meaningful relationships are facilitated, appreciative knowledge is shared, and attitudes are likely to improve. So a good example of the kind of activity that is not likely to accomplish that is a debate on a very divisive issue.

That is not likely to spread appreciative knowledge. It's not likely to develop meaningful relationships. It's simply likely to increase the polarization. Anybody thinking about their interfaith activity through the prism of the interfaith triangle is likely to design something that is different than in debate. Quite different.

Sahil: So how do we increase interfaith action on the other hand in particular? I know you say that universities should start interfaith student organizations focusing on service, and you actually work directly with universities, but what advice or ideas can you give for those outside the university or school context?

Eboo: Starting to see yourself as an interfaith leader whose vocation is connected to building interfaith bridges and creating interfaith spaces, I think is really important. As we like to say here at Interfaith Youth Core, "There's no environmentalist movement without environmentalists. There's no human rights movement without human rights activists. There's no interfaith movement without interfaith leaders." Becoming the kind of person who views it as part of their job…that's how the interfaith movement spreads.

Sahil: I'd like to now to talk about pluralism, a concept deeply related with interfaith work. At the Interfaith Youth Core, you define pluralism in three factors. You say, respect for individual religious identities, positive relations between different communities, and a commitment to the common good.

But what factors are actually negating or overwhelming the spread and understanding of pluralism in the world today?

Eboo: I think that, first of all, defining pluralism is hard, but actually living into it is really, really hard because diversity is not just samosas and egg rolls and other things that taste good. Diversity is a whole set of differences that are not easy and that you might not like. Respecting somebody's identity, even when there's a dimension of it that you deeply disagree with. It's is not an easy thing to do. If forming a relationship with them despite disagreement and finding other inspiring things to work on, that's an ethic and a skill set.

I think probably the most important things that stands in the way of accomplishing pluralism, is thinking that it's going to be easy. I think that…we need to recognize from the beginning that this is going to be hard and be prepared to do that work.

Sahil: How do you recommend the spread of it? How do you recommend its promotion?

Eboo: I think telling the story of pluralism is really important. There's a great line by the radio host Norman Corwin who would say, "Post proofs that brotherhood is not so wild a dream that those who profit by postponing it pretend." It's a rhythmic, poetic, alliterative window into -- there's a wonderful history of pluralism but we need to tell that story. We need to tell the story of Gandhi and Badshah Khan working together in South Asia.

We need to tell the story of Martin Luther King Jr., being inspired by Gandhi, and then working with Abraham Joshua Heschel. We need to tell the story of Dorothy Day starting the Catholic Worker Movement. These are stories of pluralism that we inherit across history, but we can't let those stories lie dormant, we need to tell them.

Sahil: As you might have seen, pluralism…many times gets confused with homogenization, making things similar or uniform. But in reality, pluralism means embracing and accepting difference, seeing it as part and parcel of the world so we can learn from it.

Often, interfaith work has focused on similarities rather than embracing and learning from difference. Could you speak to the importance of this, and what can be done to help increase the role of pluralism in interfaith work?

Eboo: I think clear definitions are really important and you suggested this in your question. Recognizing that deep differences exist, that those differences are often disagreements and that our challenge is to form relationships and find common ground, despite those disagreements, that kind of clear definition is a really important step towards achieving pluralism. Then inspiring people who have the knowledge-based skill set, vision and qualities to create those spaces, I think is deeply important.

Sahil: True diversity, in my view, is largely a diversity of thought, in addition to diversity of color, faith, race, culture, religion, etc.. So shouldn't we expand our understanding of pluralism to also include intellectual diversity? That's a sincere respect for other positions and opinions. We witness a lack of intellectual pluralism when certain groups are broad-brushed as a monolith. One could even argue that most conflict and discord are due to a lack of intellectual pluralism or diversity, a lack of respect for other opinions and positions.

Would you agree with this perspective and what can be done to enhance this sensibility, so…everyone can be open and respectful to new and other ideas that might oppose their worldview?

Eboo: No, I think that that's right. I think that -- I will say it again--- diversity is not just the differences you like and nor is it just the identities that you care about. People have a right to their identity. They have a right to bring it to the table and they have a right to the implications of it. Now, I think that there are lines, so I'm not interested in Neo-Nazi identity, and I'm not interested in KKK identity, but that still includes 98% of the American population.

People who are concerned of Catholics, Orthodox Jews, traditionalist Muslims, they are quite welcome along with spiritual seekers, reformed Jews, liberal Catholics, etc.. I think that recognizing the variety of identities at the table and their variety of implications matters a great deal.

Sahil: Switching gears now, you were a member of former President Barack Obama's Inaugural Advisory Council on Faith-based Neighborhood Partnerships. Could you share your experience and how you were able to increase a better understanding of faith-based alliances and…even perhaps help change the perception of religious people, in general?

Eboo: Well, I'm not sure we changed the perception of religious people in general, I think that that's a tall order. But one thing I am very proud of from the Obama Administration was the advancement of a program called the President's Interfaith Service Campus Challenge, which brought together hundreds of college campuses at no cost to the federal government who were engaged in interfaith service efforts on their campuses. I helped design that program during my year on the President's Council, and my organization partnered with the White House to make that program a reality for six years.

Sahil: Turning to the future, what guidance would you give to help Americans and the world at large, move beyond just advisory and consulting-based faith partnerships to more participatory and action-oriented faith leadership, such as your aim with the Interfaith Youth Core?

Eboo: The more people who view themselves as interfaith leaders, just like a generation of people view themselves as environmentalists or human rights activists or civil rights workers or social entrepreneurs. The more people who view themselves as interfaith leaders commit to observing the vision, learning the knowledge base, acquiring the skill set of interfaith leadership, commit to over the years, designing programs and facilitating dialogues that build pluralism, the more chance we have to advance this movement and to really build those bridges.

Sahil: On the same train of thought, great thinkers also often reflect about a vision for the future. We normally talk about these in general terms, but could you name a specific objective that you could see the world can achieve, let's say in 25 to 50 years? And what insights and suggestions would you offer that might help them address and achieve this vision?

Eboo: Well, we talk a lot here at Interfaith Youth Core about interfaith cooperation becoming a social norm. So what would be some of the signs of that? Our work is limited largely to the United States, so I'll just speak in the American context for a minute.

Every small and large city in the United States had a day of interfaith youth service, and the Mayor of that city, be it New York or Louisville, or Houston or Dayton, Ohio, was present at that day of interfaith youth service and cut the ribbon on it, just like cities have marathons, and they have Environmental Cleanup Days and Martin Luther King Day celebrations--- it's just part of a city's calendar.

Similarly, what if every city had a day of interfaith youth service? What if a typical question that the hiring committee of a synagogue or a masjid or a gurdwara or a church, what if a typical question for a clergy person they were hiring was, "how do you plan to build interfaith cooperation in your role as our lead clergy here?" Just like, I imagine, committees ask these days about how that person tends the whole worship services and how that person intends to take care of the facilities over the coming years.

What if interfaith cooperation was one of those kinds of questions? What if every college in the United States had an interfaith student council? What if…there were interfaith councils in every city across the United States? These are the kinds of signs that would indicate interfaith cooperation becoming a social norm.

Sahil: And to end on a lighter note, what symbolizes great leadership to you? What attributes of leadership, particularly interfaith leadership, do you personally admire?

Eboo: I really think that being a leader comes down to one thing, and that's people looking at that person and saying, "I believe you." That's what being a leader is, it's other people believe you. It doesn't just mean that they believe in you, but they believe you. I go see Bruce Springsteen every time he comes to Chicago, and the reason is simple. It's because I believe him.

This interview has been re-published from OnFaith (onfaith.co) with permission.

About Eboo Patel

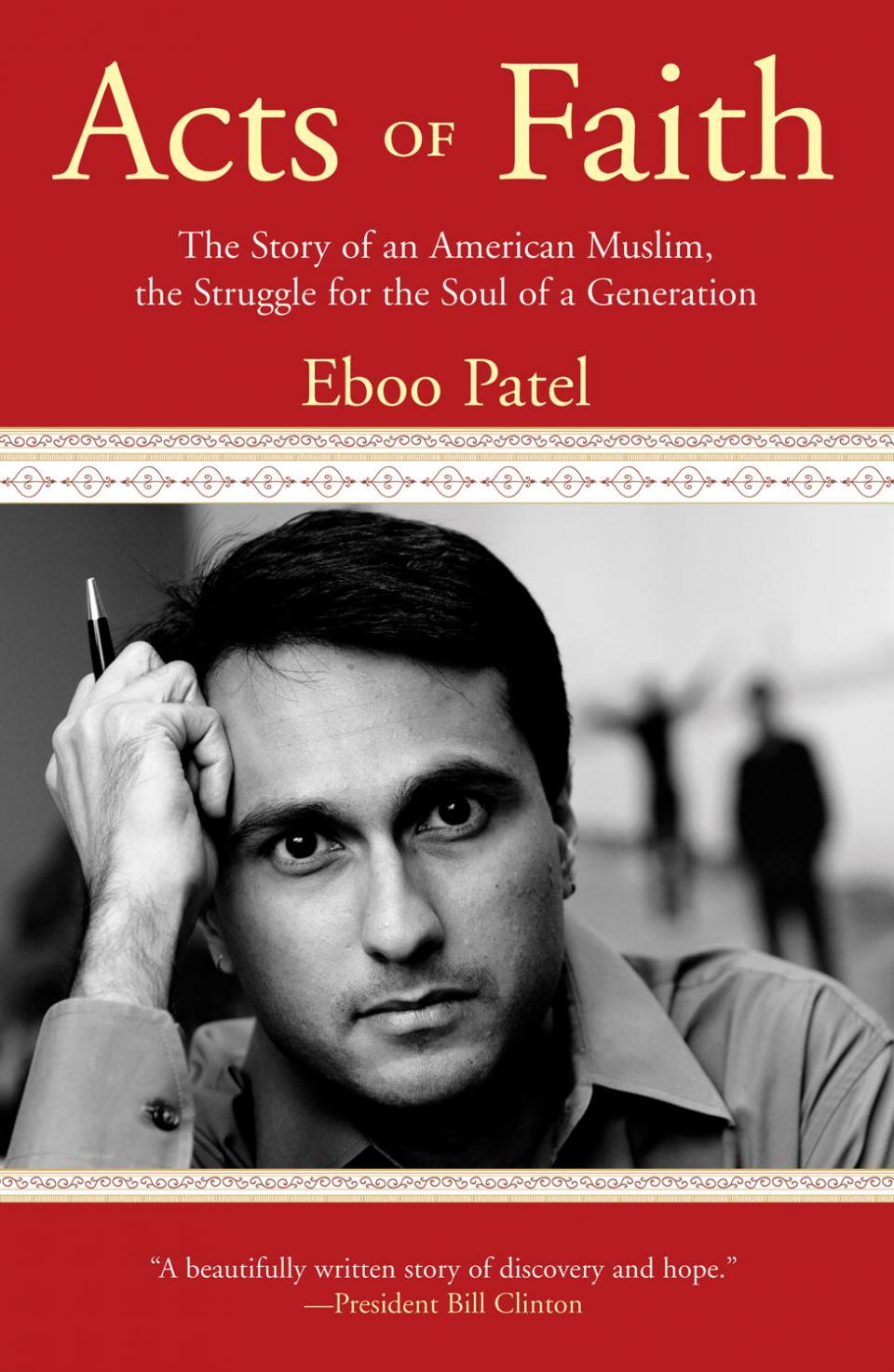

Eboo Patel is a leading voice in the movement for interfaith cooperation and the Founder and President of Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC), a national nonprofit working to make interfaith cooperation a social norm. He is the author of Acts of Faith -- which won the Louisville Grawemeyer Award in Religion; Sacred Ground, and Interfaith Leadership: A Primer. Named by US News & World Report as one of America’s Best Leaders of 2009, Eboo served on President Obama’s Inaugural Faith Council. He is a regular contributor to the public conversation around religion in America and a frequent speaker on the topic of religious pluralism.

He holds a Doctorate in the Sociology of Religion from Oxford University, where he studied on a Rhodes scholarship. For over fifteen years, Eboo has worked with governments, social sector organizations, and college and university campuses to help realize a future where religion is a bridge of cooperation rather than a barrier of division. Website: www.ifyc.org;

About the Interviewer

Sahil Badruddin is a graduate of The University of Texas at Austin with degrees in Chemical Engineering, Religious Studies, and History. He conducts interviews with influencers, leaders, and intellectuals for various platforms to discuss their insights on contemporary issues. Some of his recent interview guests, among others, include Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Karen Armstrong, Shainool Jiwa, Ali Velshi, and Hasan Minhaj.