For many women, bringing a baby into the world is a joyous experience. But tragically, this is not the case for all expectant mothers, particularly those who live in vulnerable societies.

According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 289 000 maternal deaths were reported globally in the year 2013. In other words, 33 expectant mothers died every hour last year.

Women in developing countries suffer the worst. While the lifetime risk of maternal death for a woman living in a country like Canada is one in 3 700, the risk for a woman in South Asia is one in 200, and climbs to an astounding one in 38 for Sub-Saharan Africa.

At a summit of G8 leaders held in June 2010, Canada called for a multi-national commitment to “reduce maternal and infant mortality and improve the health of mothers and children in the world's poorest countries.” Prime Minister Stephen Harper made maternal, newborn and child health Canada's top development priority.

“Poor nutrition and preventable diseases continue to claim the lives of an unacceptable number of women, children and newborns, despite strong international efforts and progress,” said Prime Minister Harper.

Building on that commitment, Canada is hosting an international summit in Toronto between 28 – 30 May that will bring together global leaders and seek ways to reduce mortality rates and improve maternal, newborn and child health in the most vulnerable parts of the world. “Through this summit and our ongoing engagement and support, Canada will help to ensure that the world continues to focus on these critical issues,” said the Prime Minister.

Legacy of quality health care

Providing expectant mothers and newborns the highest quality of care, and giving children the best start in life is part of a value system that Ismaili Muslims have practiced for generations.

During the 19th century, Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah, the 48th hereditary Imam of the Shia Ismailis, guided his community towards a modern approach to healthcare. In India and East Africa he established dispensaries, clinics and hospitals, ensured that they were well equipped and well staffed, and encouraged the community to make use of them.

Ismailis like Sewa Hajji Paroo and Varas Sir Tharia Topan followed the Imam's example, commissioning community hospitals and dispensaries in places like Bagamoyo (in present-day Tanzania) and Zanzibar. In later decades, many of these facilities would be further upgraded and consolidated within the Aga Khan Health Services.

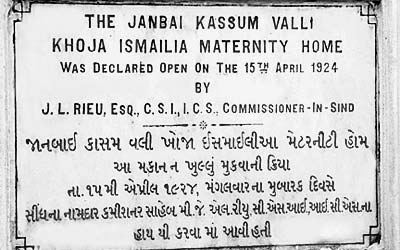

Plaque commemorating the opening of the Janbai Maternity Home on 15 April 1924, now the Aga Khan Hospital for Women and Children in Kharadar. Courtesy of AKHS, Pakistan

Plaque commemorating the opening of the Janbai Maternity Home on 15 April 1924, now the Aga Khan Hospital for Women and Children in Kharadar. Courtesy of AKHS, PakistanThe care of expectant mothers was a central concern, and maternity homes were opened in many communities where the Ismailis had a presence. The Aga Khan Hospital for Women and Children in Kharadar, Pakistan was established through the philanthropic efforts of Vazir Bundeh Ali Kassim, with the support of Mawlana Sultan Mahomed Shah. Inaugurated in 1924, it was originally called the Janbai Maternity Home after Vazir Kassim's mother, and the hospital's 24 beds are said to have been furnished with the latest medical equipment of the time.

Today, the health system of the Aga Khan Development Network delivers maternal, newborn and child health care at some 180 health centres around the world, including 13 hospitals. Last year, 60 per cent of the network's 4.7 million patient visits were mother and child related. This included 41 000 deliveries, antenatal and postnatal care, child immunisations, growth monitoring, health promotion and disease prevention.

But the challenges of maternal health cannot be addressed exclusively within the confines of hospital walls. According to the Aga Khan Health Service, Pakistan, a large proportion of deliveries in the country are home deliveries, with only 43 per cent taking place with a skilled birth attendant – a factor that contributes to maternal mortality. To help address this, Aga Khan women's hospitals in Kharadar and elsewhere in Karachi and Hyderabad train midwives through a recognised diploma programme. With the skills they gain, these midwives can offer better support to expectant mothers in their homes, help to ensure safe deliveries and identify and resolve risks early on, before they become significant threats.

Educate mothers and care providers

In 1999 he was among a team of specialists that took part in a three-year project in Khorog, Tajikistan, aimed at improving the quality of healthcare in the high mountain region. The Soviet collapse had impoverished the population, and quality of life had deteriorated. Maternal-child morbidity and mortality had surged and the health system was challenged by a scarcity of resources.The education of mothers also plays a vital role in the survival of newborns and early child development. Dr Naz Bhanji, a pediatrician based in British Columbia, Canada, learnt this firsthand.

Faced with these conditions, Dr Bhanji discovered that educating mothers – not just the care providers – could have a significant impact, and he began to see it as a major driver of change. Teaching women about matters of health and nutrition so that they can make well-informed decisions for their families, he asserts, can prove far more effective in bringing about change than simply trying to implement innovations that have worked here in Canada.

“You cannot import ideas from the West and just implement them,” says Dr. Bhanji. Even healthcare providers and policy makers who study in the West must learn to translate the knowledge they have gained back to their local context. “A lot of these ideas may not work effectively in the developing world. You have to be innovative to develop solutions that are locally created.”

Dr Bhanji also notes that educating primary care providers – particularly nurses and allied health professionals – has led to some of the greatest successes, because they are more able to penetrate the rural populations. They improve health outcomes by promoting primary health, education and baby care. He stresses the importance of actually being in the community, as these health professionals are everyday, and thinks that all physicians should spend some time working with nurses and nurse practitioners in remote and rural areas.

Promise of research, knowledge and innovation

Saima Hirani, an assistant professor at the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery, hopes to adapt the knowledge she gains in Canada to her teaching, practice and research in Pakistan. Courtesy of Saima Hirani

Saima Hirani, an assistant professor at the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery, hopes to adapt the knowledge she gains in Canada to her teaching, practice and research in Pakistan. Courtesy of Saima HiraniDr Bhanji's advice would not be lost on Saima Hirani, an assistant professor at the Aga Khan University School of Nursing and Midwifery in Karachi.

Hirani is currently pursuing a PhD in Nursing at University of Alberta in Edmonton. She is particularly interested in the area of mental health, and plans to incorporate the knowledge that she gains in Canada into her teaching, practice and research in Pakistan.

“My doctoral research aims to improve women's resilience by enabling them to address their life adversities,” says Hirani. “In the long run, such interventions may contribute immensely towards the well-being of the families especially raising mentally healthy children.”

In fact much of the hope in addressing the dismal condition of mothers and children in vulnerable societies may rest in research, and the advanced knowledge that it produces. Combined with technology and innovative creativity, it has the potential to bring life-saving interventions to populations that could not previously be reached.

“We have the knowledge and the tools to save mothers' and newborn lives”, says Beth Payne, a PhD student at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver. Together with researchers in Canada, South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, her team is testing a mobile phone-based health application that promises to identify women and babies who are at increased risk of pre-eclampsia.

A pregnancy disorder that is linked with high blood pressure, pre-eclampsia can develop into eclampsia, a condition that threatens the lives of mother and child. Payne says that the mobile app is designed to guide community health workers through an assessment of a woman with high blood pressure in pregnancy, allowing them to target life-saving drugs to those identified as the most sick and in need.

“I believe women are key to the success of any society and recognise that I have been lucky to have been born into a very privileged and safe position as a woman in Canadian society,” she says. “I would like to make use of this position to support change for the better for women elsewhere.”

Building on a partnership of success

Ismailis in Canada share this sense of good fortune and the desire to help others. Whether through individual initiative or on a community-wide basis, they are reaching out to partner with government, civil society, friends, and neighbours across the country to leverage the strong institutional foundations that their parents and grandparents helped build in Africa and Asia.

“For decades, Aga Khan Foundation Canada has been working with Canada and Canadians, and our partners in the Aga Khan Development Network, to improve maternal and child in Asia and Africa,” says Khalil Z. Shariff, Chief Executive Officer of Aga Khan Foundation Canada. “Supporting the health of women and ensuring that all children get the right start so they can survive and thrive are essential for a healthy society.”

The Foundation's World Partnership Walk has been a fixture in cities across the country for 30 years, raising funds and spreading awareness of the problems in the developing world – as well as solutions. Canadians have supported the Walk enthusiastically, raising some CAD $82 million over three decades and have made a tangible difference in the quality of life of millions of people.

“The Saving Every Woman, Every Child: Within Arm's Reach summit is an opportunity for the global community to ensure this issue remains a priority,”adds Shariff. “Together, we can deliver real results for mothers and children around the world.”