When Nadir Hassanaly and his friends stepped off the plane at Nairobi's Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, only a few of them were comfortable speaking in English. The rest preferred to stick with French, the language of their island home of Madagascar – at least for the time being. But that would change over the next several days.

In April 2010, 13 Malagasy students visited Kenya where they made new friends while immersing themselves in the country's culture as they improved their English language skills. Courtesy of the Ismaili Council for Kenya

In April 2010, 13 Malagasy students visited Kenya where they made new friends while immersing themselves in the country's culture as they improved their English language skills. Courtesy of the Ismaili Council for KenyaTheir trip in April was part of a language immersion programme organised by the Jamati Education Committee of the Ismaili Council for Kenya. It gave the 13 Malagasy students an opportunity to experience a culture outside their own, make acquaintances and friendships with Ismaili students from another country, and to immerse themselves in an environment where they could improve their spoken and written English. It was also a chance to better understand the work of the Aga Khan Development Network in Kenya.

“Our arrival in Nairobi was just the beginning of a series of happy experiences,” said Hassanaly, who recounted the warm welcome that the group of 13 – 15-year-olds received. “They took us immediately to the Jamatkhana Hall where a big party was organised for us.”

At Parklands Jamatkhana, nervous smiles gave way to excited chatter as the Malagasy students were introduced to their host families. The visitors had been paired with students who attended Nairobi's Aga Khan Academy and Aga Khan Junior Academy. Everybody got to know one another over hot chai and fresh samosas – universal comfort foods for Jamats from Nairobi to Antananarivo.

The visiting students settled in well at their hosts' schools – although classes being conducted in English rather than French took some getting used to, as did the longer Kenyan school hours. Joining their hosts at school was an important part of the immersion experience, as it highlighted the social nuances as well as the linguistic differences of a classroom environment in Kenya.

A variety of excursions were planned throughout the week, including trips to the Kibera slum, the United Nations and Nairobi's Village Market. Hassanaly explained that the group learnt about the main bodies of the UN, including the World Health Organization and UNICEF. “[An] Ismaili man who works there explained everything to us,” he said.

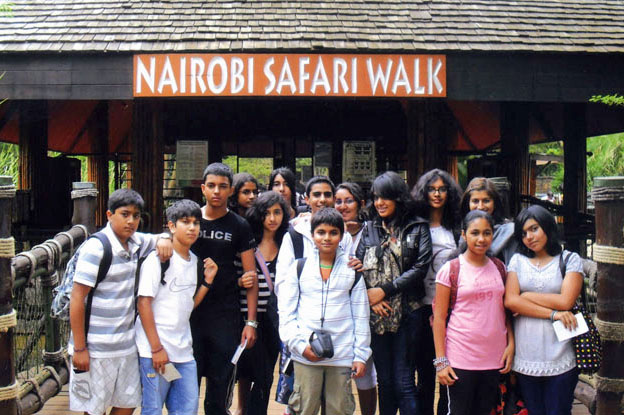

Despite being home to a unique mix of plants and animals – many of which are found nowhere else in the world – Madagascar's ecology has been severely endangered by human activity. Students were therefore particularly excited to experience some of Kenya's wildlife during visits to the animal orphanage and the Nairobi Safari Walk. “Even though we did not meet the giraffes, we could caress a cheetah,” exclaimed Hassanaly – “a real one!”

Students from Madagascar were excited to experience some of Kenya's wildlife during a visit to the Nairobi Safari Walk. Courtesy of the Ismaili Council for Kenya

Students from Madagascar were excited to experience some of Kenya's wildlife during a visit to the Nairobi Safari Walk. Courtesy of the Ismaili Council for KenyaA visit to Kibera – a severely impoverished Nairobi neighbourhood with an estimated 1 million inhabitants that is the second largest urban slum in Africa – made a strong impression on the students, many of whom had no idea that such immense poverty existed. Hassanaly was impressed by the Community Cooker Project. People in Kibera “collect waste and use it for cooking,” he explained. “There are four women who do the cooking every evening. They make cakes and other things and sell them to the people of the shanty town to earn some money. And we tasted spinach and bread there! It was very interesting to see these people.”

In addition to the excursions, host families organised various activities from barbeques to bowling trips, and the Jamati Education Committee, Nairobi arranged a dinner for the students and their hosts to mark the end of the week-long trip. The programme promoted multiculturalism, unity and brotherhood across Jamats in the two East African countries, but its greatest success was visible in the newfound confidence that the Malagasy students exuded when conversing in English.

“At the beginning, many of us could not speak English correctly – our conversations were a lot of yes's and no's,” observed Hassanaly. “But after [this week], everybody could speak English using longer sentences, and take part in real conversations. We even spoke English between ourselves!”