Alnoor Merchant addresses the audience at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Courtesy of the Ismaili Council for the USA

Alnoor Merchant addresses the audience at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston. Courtesy of the Ismaili Council for the USA“He gave quite a lot of information, but within a narrative that held the audience's attention with stories and there were even a few moments of suspense and intrigue,” said Dr Kathryn Woodard, an Assistant Professor at Texas A&M University in College Station.

She was commenting on a talk delivered by Alnoor Merchant, Acting Head Librarian and Keeper of the Manuscript Collections at the Library of the Institute of Ismaili Studies in London. Merchant recently conducted a four-city lecture series on Muslim artistic, scientific, and architectural patronage. The lectures were held at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, Stanford University, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in February 2009.

Captivating his audience with an array of historic artefacts from the Aga Khan Museum collection, Merchant described their origins and the important role played by patrons in the history of Islamic art. He recounted the exuberance and dynamism of artistic environments established from Indonesia to Spain by patrons who attracted celebrated artists to create vibrant and unique masterpieces.

Although patronage of arts was primarily practiced by the royal court, it expanded to include other wealthy individuals and affluent business merchants. Merchant explained that these works of art were not only made to grace the royal court – they also reaffirmed relationships between the king and his people.

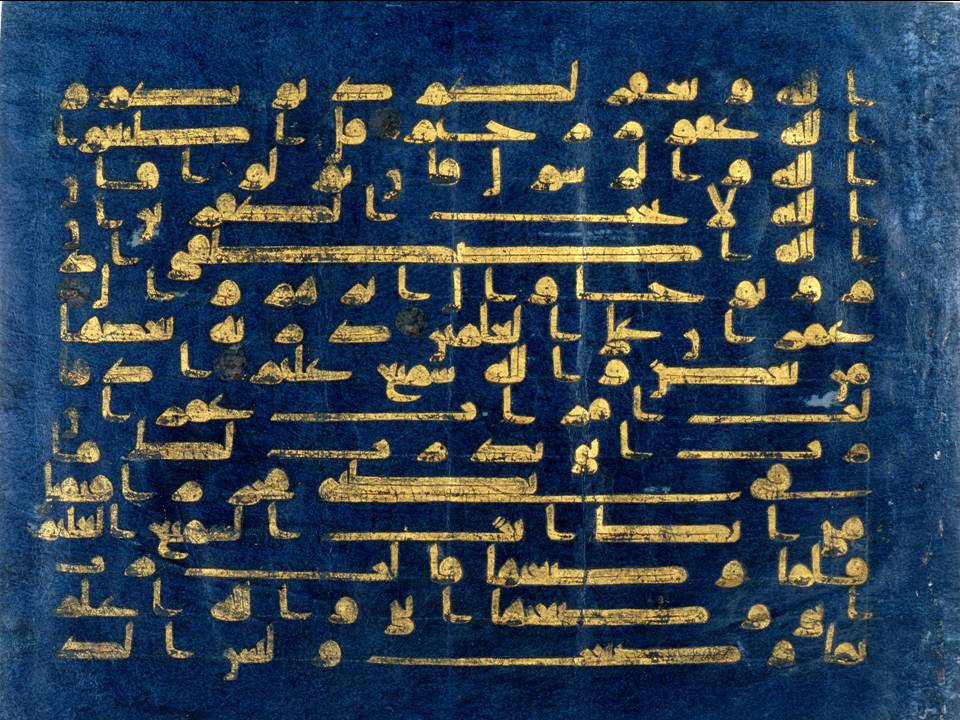

Folio from the Blue Qur'an – North Africa, possibly Qayrawan, 9 – 10th century. Courtesy of Alnoor Merchant

Folio from the Blue Qur'an – North Africa, possibly Qayrawan, 9 – 10th century. Courtesy of Alnoor MerchantCommencing his lecture with an artistic leaf from the famous Blue Quran, Merchant noted that beautifully decorated manuscripts adorned with calligraphy were perhaps the most essential elements of Islamic art. One of finest examples of Quranic productions, the Blue Quran is written on blue parchment in gold kufic script.

Recalling that the first revelation received by Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him and his family) opens with the injunction Iqra – which means “recite” or “read” – Merchant asserted that Allah “taught man by the pen that which he knew not,” (in reference to Surah 96). “Here the importance of learning and knowledge is very fundamentally linked to the Islamic ethic,” he explained.

Beyond Quranic manuscripts, patrons supported other artistic creations including glassware, pottery, textile, ceramics, and even jewellery, which were often adorned with calligraphy, arabesque, and figural motifs of birds, animals and even human faces. Merchant delighted audiences with pottery from the tenth century bearing an inscription that reflected one of the traditions of the Prophet: “Generosity is at the disposition of the dwellers of paradise.” The Museum of Fine Arts may wish to use this piece for fundraising purposes, quipped Merchant.

Illuminated manuscripts and miniatures were also favoured by patrons. Miniature paintings date back to the 1630s and were particularly important within the Persian and Mogul traditions. Merchant showed several examples of colourful miniatures, mostly depicting intellectual and spiritual discussions.

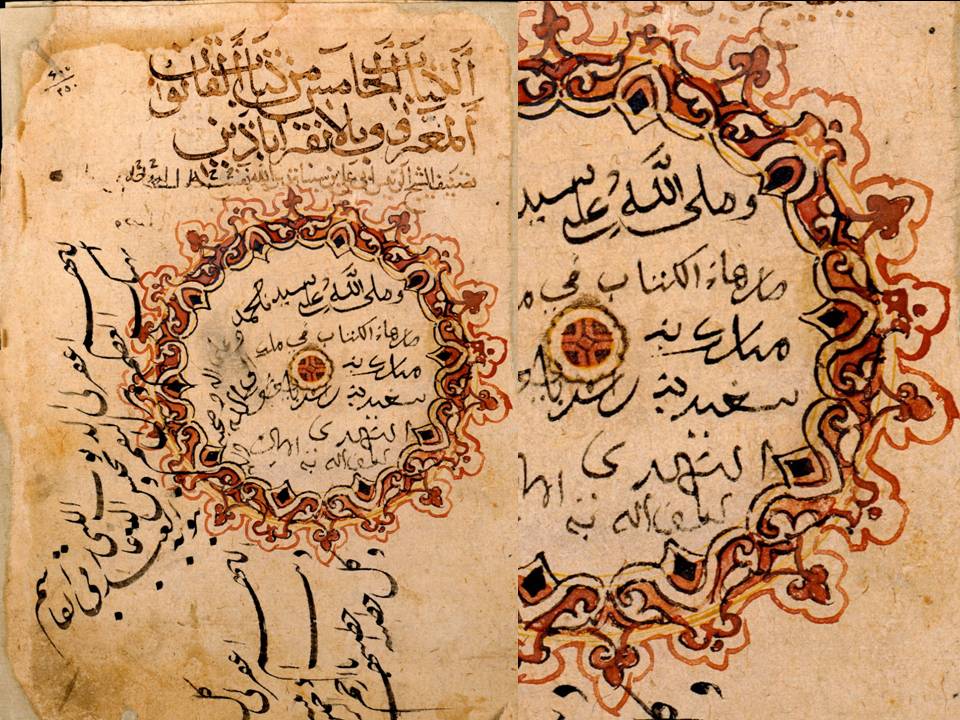

Manuscript of the Qanun fi'l-tibb of Ibn Sina, vol 5 – Iran or Mesopotamia, dated 444 H / 1052 CE. Courtesy of Alnoor Merchant

Manuscript of the Qanun fi'l-tibb of Ibn Sina, vol 5 – Iran or Mesopotamia, dated 444 H / 1052 CE. Courtesy of Alnoor MerchantOne example portrayed a discussion exchange between a prince and a number of scholars. In many of the paintings intellectual discussions were symbolised as spiritual nourishment through accompanying illustrations of water, which Merchant explained symbolised bodily nourishment: “Even today this is what you find in an architectural setting, where you will find perhaps a Quran school on a level above a fountain.”

Music was another important form of patronage in Muslim civilisations. Merchant showed an example of a miniature that illustrated the work of Nasir al-Din Tusi, a thirteenth century philosopher and astronomer, whose work was patronised by the Ismaili rulers of Alamut. The miniature had illustrations of music, yet it accompanied Tusi's work on ethics. Merchant explained by quoting Tusi: “No relationship is nobler than that of the equivalence, as has been established in the science of music.”

“The most significant visual element, even today, is the patronage of buildings,” said Merchant. He noted that the finest craftsmen were recruited from across the Muslim world to build impressive monuments that demanded superb decorations, tiled interiors and painted exteriors. This led to a discussion on geometric motifs, which were sometimes used in combination with calligraphy, arabesque, and figural motifs. The repeating geometries constitute infinite patterns that symbolically extend beyond the material world. For many, geometry provides a spiritual representation of the infinite nature of Allah's creation.

Turning to the Aga Khan Museum, which is due to open in Toronto, Canada, Merchant noted that it will be dedicated to the acquisition, preservation and display of artefacts from various periods and geographies, relating to the intellectual, cultural, artistic and religious heritage of Islamic communities. Mawlana Hazar Imam “has identified the need for greater engagement between the East and West,” said Merchant. “The primary objective of this museum is to use culture and art towards creating an educational understanding between communities; to show the diversity and the pluralism that exist within the artistic traditions of Islam.”

Audience members were appreciative of the lecture. “Both my husband and I enjoyed this program,” said Faranak Zafarnia, President of the Society of Iranian American Women for Education.

The lectures were made possible through the generous support of The Institute of Ismaili Studies, in collaboration with the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and the Ismaili Council for the United States.