7

Danish specializes in creating dynamic spaces for learning, innovation and creativity, improving access to education globally. He also designs spaces for social justice, environmental preservation, equity and inclusion, women's rights and equal opportunity. Danish’s award-winning work has been recognized by numerous organizations including the OECD, World Cities Summit, and US State Department. His students at Harvard University and Stanford University are fortunate to learn from his multidisciplinary approach focused on "Design Anthropology,” combining spatial thinking and anthropological research innovatively to tailor designs on a community-by-community basis.

Architectural Influence on Society

“If you think about your daily experience in the world, it really has two parts: there’s the natural world and the man-made world. The man-made world is primarily products or architecture -- buildings, transportation systems, and cities. Not a single person in the world goes a day without encountering architecture,” says Danish. The importance of architectural design often goes understated and underappreciated, because we don’t think about things until they’re broken. “If a power line goes down, we’re up in arms about why we don’t have power, but if the power line is working just fine, we’re not even thinking about it,” notes Danish, “similarly, architecture has this tremendous impact on our daily life that we’re not privy to.”

Danish is partial to a broad definition of architecture, encompassing the macro-scale of urban design to the micro-scale of the chairs we sit in. Danish shared a humorous yet very telling example from childhood about how the architecture in his house was actually embedded in his daily rituals, affecting his habits. “Growing up, my bathroom was the furthest from the water heater on the other side of the house. When I turned on the hot water, it took several minutes to get hot, and so often I would say, ‘Forget it, I’m not going to wash my face tonight!’ because it felt wasteful to let so much cold water pour down the drain while I waited for hot water. The smallest, most mundane, banal things that we take for granted and don’t really think about, that’s still architecture,” emphasizes Danish.

In addition to functional utility, architecture deeply impacts our psychology. Danish offers tangible examples of architectural influences on these instant feelings we get: “You walk into New York Public Library on 42nd Street with its soaring, tall, open, airy, well-lit reading rooms filled with stacks, and it gets you in a certain mindset.” On the other hand, at the Ismaili Center in Houston, Danish notes, “the prayer room is darker, a bit more somber with teardrop lights. I love being in that space because it feels like a place for prayer. It’s dim enough such that you’re not being distracted by what’s happening around you. The architecture reminds you of Prophet Muhammad going up to Mount Hira to meditate in a cave.”

Not only does architecture evoke instant emotions, but it also underlays a subtler, more persistent aspect of our psychology. Danish offers a compelling argument as to why the architecture of public transportation networks affects our levels of tolerance. Danish compares car-dominant cities such as Houston, Atlanta and Los Angeles, to cities with a greater availability of public transportation, such as New York or Boston. Contrasting these opposite ends of the spectrum, Danish asserts, “in the cities that are car-dominant, you’re in your house, you get into your car which is a private bubble, and then you get to your office surrounded by people who are presumably quite similar to yourself. Compare that to riding the subway in NYC, and it’s a whole cast of characters. On your commute, you’re encountering ten different languages, people of different ethnicities, ages, income levels and belief systems, all crammed into a single subway car. Just by sheer exposure to that, there’s immediately less fear of the unknown. Because you’re rubbing shoulders with them and forced to share space with people who are not like you, it affects levels of tolerance in an almost imperceptible way. That’s the power of architecture.”

Architectural Heterogeneity as a Necessity

Danish aptly argues that it’s a misnomer to characterize an architectural style as Islamic. “Islam is not homogenous, so then to think about a single style of architecture and call that Islamic is actually in opposition to what Islam looks like in practice,” says Danish. There’s architecture that makes sense for certain geographies, for example, Muslim countries in Far East Asia compared to those in the Middle East would have dramatically different architecture sensitive to their disparate climates and ecologies.

Danish continues, “if you tried to devise a set of principals of what Islamic architecture could look like, it would be architecure that takes into account the fundamental tenets of Islam, such as compassion.” Danish cites various examples such as choosing to build homeless shelters, orphanages and medical clinics which are inherently compassionate endeavors, or it could be responsible architectural stewards who take care of the natural world in sustainable ways. “Minarets and geometric patterns are just aesthetic, they don’t necessarily have to do with any of the values of Islam. Just like tariqas within the faith have varying interpretations, they all share fundamental values of generosity of spirit and remembrance of the Divine. The architecture itself will look different, but it’s architecture that embodies these principals that would be the closest thing to saying, ‘this is Islamic architecture.’”

Educational Advancement Through Architecture

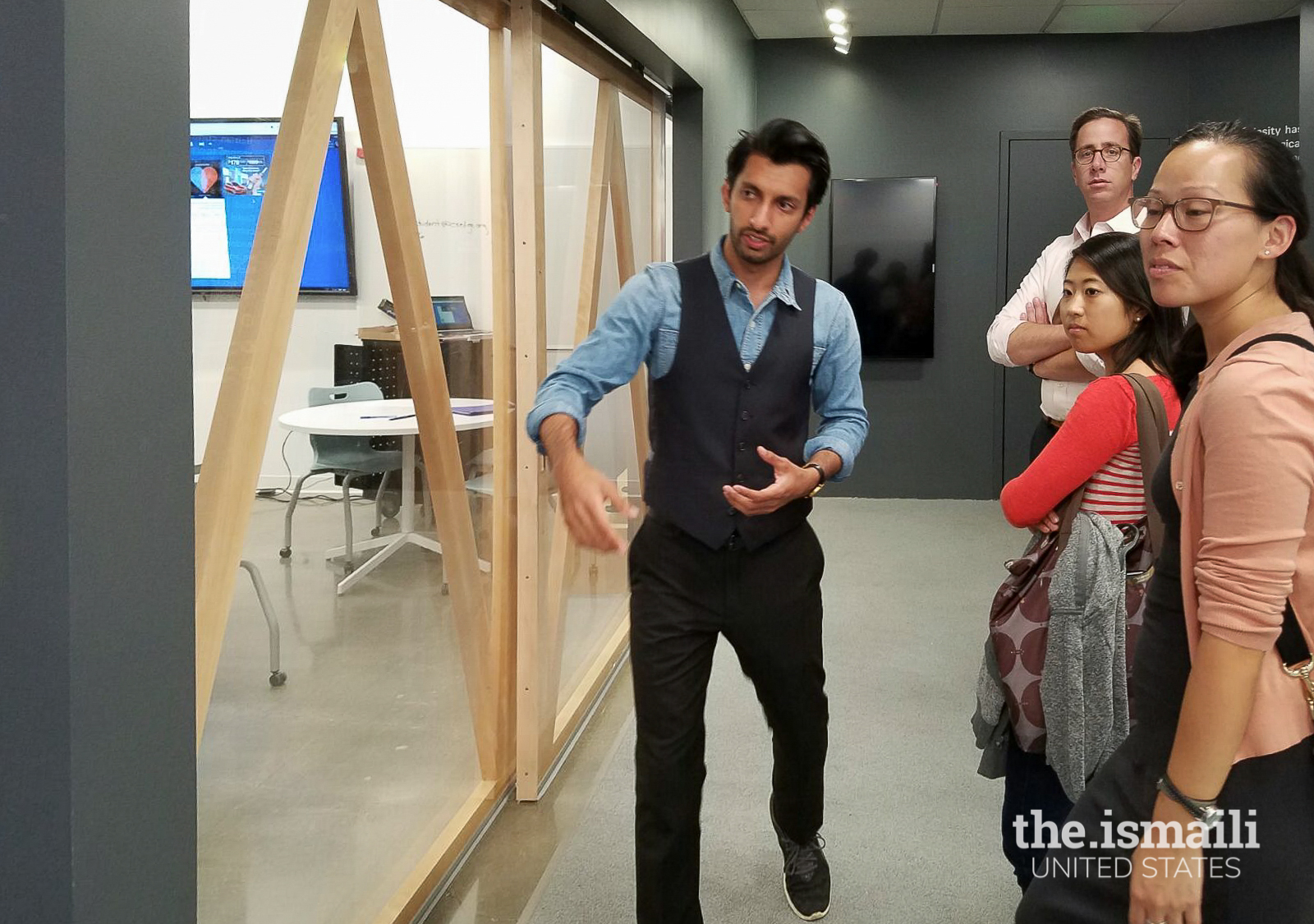

Danish specializes in architecture for education, designing spaces to help people of all ages learn in their own way to better themselves, their families, their communities, and, ultimately, their world. Danish was asked to design a series of elementary school classrooms in Denver funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to personalize education for young kids, since the current architecture was actually holding the students captive rather than holding the space for their fullest expression. “Hallways, square classrooms, teachers up front at the blackboard, and students in rows in their seats were designed for churning out factory workers instead of nurturing the gifts that lie within each child,” Danish shrewdly points out. Continuing to build classrooms with century-old designs is analogous to investing in flip phones or fax machines today. “Now we're trying to build innovators, inventors, scientists, programmers, collaborators — and it requires a new look at the classroom,” says Danish. Danish put deep thought into how the architecture within a single classroom could be sensitive to 20 young minds having potentially 20 different learning styles, such that “the architecture itself, in a way, puts its arms around the children and makes them feel that whatever you want to do, you can do here, and we’ll support you.”

Another instance of Danish designing for the modern age of education was through his work at Riverbend, a boarding school in Chennai, India, that approached him with a revolutionary idea: how do we prioritize students’ happiness over test scores? Before any designs or blueprints were drawn up, Danish conducted heavy research in the fields of anthropology and sociology and found the most comprehensive, longitudinal study on happiness written by his colleagues at Harvard that tracked the lives of hundreds of individuals to find that happiness is not derived from professional success, fame or wealth, but from the quality of your relationships. “Given this insight, how do we design a campus that cultivates meaningful relationships?” Danish asked. Fortuitously, a few years prior, Danish had seen a documentary entitled The Economics of Happiness, in which anthropologists concluded that happiness and relationships are strongest in small villages, since living in large cities eroded social fabrics as it created isolation and a lack of community. Subsequently, Danish studied the history of village design and modeled the campus accordingly to bring ancient wisdom into the modern age.

Architectural Strides and Setbacks

Danish urges us to let go of nostalgia of how architecture used to be constructed, “since architecture is so fundamentally wrapped up with the social, political and economic state of the world. It doesn’t make sense to emulate what was done then, since what worked previously may not be appropriate now.” Back then, the mindset was that “all of the money, energy, thought, material resources, and ecological toll that it takes to create this building is worth it, since it’s going to serve our community for a long time,” says Danish, “but now, buildings are erected with a very short lifespan. Now with our throwaway mentality, in which we’re replacing our phones every year, if we can’t easily repair something, we just trash it and buy a new one.” As he sees this happening with architecture, Danish is rightfully concerned about the strain on finite resources, as this waste is happening on a whole different scale. “I’d like to see architecture not follow the trend of this dangerous mentality we have toward our products,” warns Danish.

In regard to the timeless architectural debate of form versus function, Danish pleads, “I wish architects cared more about how something worked and how it supports people and improves their lives, and less about making something look cool, trendy, flashy, and Instagram-worthy.” Given our finite resources, Danish finds it wasteful that many architects today are “so focused on creating the image of what modern architecture is, that it results in spaces people hate being in. They forget how humans actually live, what they prefer, what makes people comfortable, happy, and joyful.”

The Influence of AKAA on Designing Community-Centric Architecture

“The Aga Khan Award for Architecture (AKAA) has put a spotlight on architecture for the general public. Most people know the Pulitzer Prize and the Nobel Prize, and learn about literature and science through these awards. Similarly, the AKAA has helped architecture as a field become more mainstream and has highlighted architecture’s importance for the masses,” says Danish. In regard to how the AKAA has changed the conversations about the environment, green spaces, and the preservation of historic sites and monuments, Danish notes that it’s the AKAA in concert with the Aga Khan Planning & Building Services, Historic Cities Programme, and the Trust For Culture that come together to bring architects' voices to the table to affect change.

The other way in which the AKAA has changed the conversation, Danish says, is “by virtue of being a prestigious award that the design community respects and pays attention to, it indirectly influenced leading architects to even consider projects in Muslim countries, to think beyond the geography of the West and understand that the rest of the world is worthy of their consideration, time, energy, and social and intellectual capital.” Danish acknowledges that the award goes beyond superficial factors and considers the impact on communities, since recipient architecture “may not look shiny, new or extravagant, but when you dive in deeper, you see how a community came together to build a medical clinic, or a school was built near families so students didn’t have to walk ten miles and cross a river to get there.” Due to the fact that the AKAA celebrates projects with impact, Danish notes, “it pushes architects to let go of superficial aesthetics and think about the impact their work has on people.”

Building from the Heartspace

“We need to step back as a society and think about our ultimate goal for education: we are shaping people in the image of the world we aspire to be in,” says Danish, “I find incredible visionaries who are trying to achieve something in the world that I personally believe in and want to back, and I ask myself, how do I create architecture that will support them and their mission to help bring this to life?” Danish’s conscientious architecture involves the end users in the design of the space that they will inhabit to set up dynamic communities for long-lasting success. Danish has been so successful because his work unwaveringly aligns with his values, and his ethical core manifests in the spaces he creates.

For more information on Danish Kurani, visit his website, and view his TEDx Talk entitled, “Designing Places for Learning.”