Social scientists from another planet might be excused at being nonplussed at what they would observe here on Earth. They might admire humanity’s achievements in space exploration, genetics and artificial intelligence, our copious production of art and literature, and recent advances in living standards that are unsurpassed in human history. However, looking a little closer, they would also see the environmental degradation we have caused, the destructive impact of climate change, resurgent conflicts between peoples around the world, growing tensions over access to land, food and water, and an increasingly inequitable distribution of wealth, with the majority of the world surviving at or below poverty level.

Francis Fukuyama's much heralded book The End of History and the Last Man, published in 1992 after the fall of the Iron Curtain, posited the triumphal global acceptance of liberal democracy. Two decades later, in stark contrast to his anticipation of global peace and prosperity, previously stable societies are under threat and newly risen economies are challenging the status quo.

In some corners of the world, political and press freedoms are being curtailed, and violence against citizens and minority communities is spreading. Despite progress in so many arenas, tribal passions and self-interest remain part of the psyche.

The fallout can be seen in massive displacements of people — most recently from Syria and North Africa — in which populations are being forced to leave their ancestral lands. Societies elsewhere struggle to accommodate sudden and large influxes of immigrants, causing stress for governments and host communities.

“We now accept diversity in nature and among peoples as a reality within our world,” says Professor Azim Nanji, who sits on the Board of Directors of the Global Centre for Pluralism in Ottawa. “However in committing ourselves to a notion of pluralism, we are discovering that the peaceful acceptance and valuing of difference among people, remains a major challenge.”

Established by Mawlana Hazar Imam and the Government of Canada, the Global Centre for Pluralism seeks to better understand the foundations of successfully pluralistic societies and influence policies that can help advance pluralism elsewhere.

Sadly however, polarised factions are becoming more extreme and irreconcilable. The nationalist movements of today are fed by the perceived erosion of traditional cultural identities.

Technology has not proven to be the panacea for the ills of society as was once promised. While it brings voices and images of people from around the globe into our living rooms or onto our mobile devices, this has not led to the sharing of deeper mutual understanding.

“More communication has not meant more cooperation. More information has also meant more misinformation,” observed Mawlana Hazar Imam. “And it has also meant more willful disinformation.”

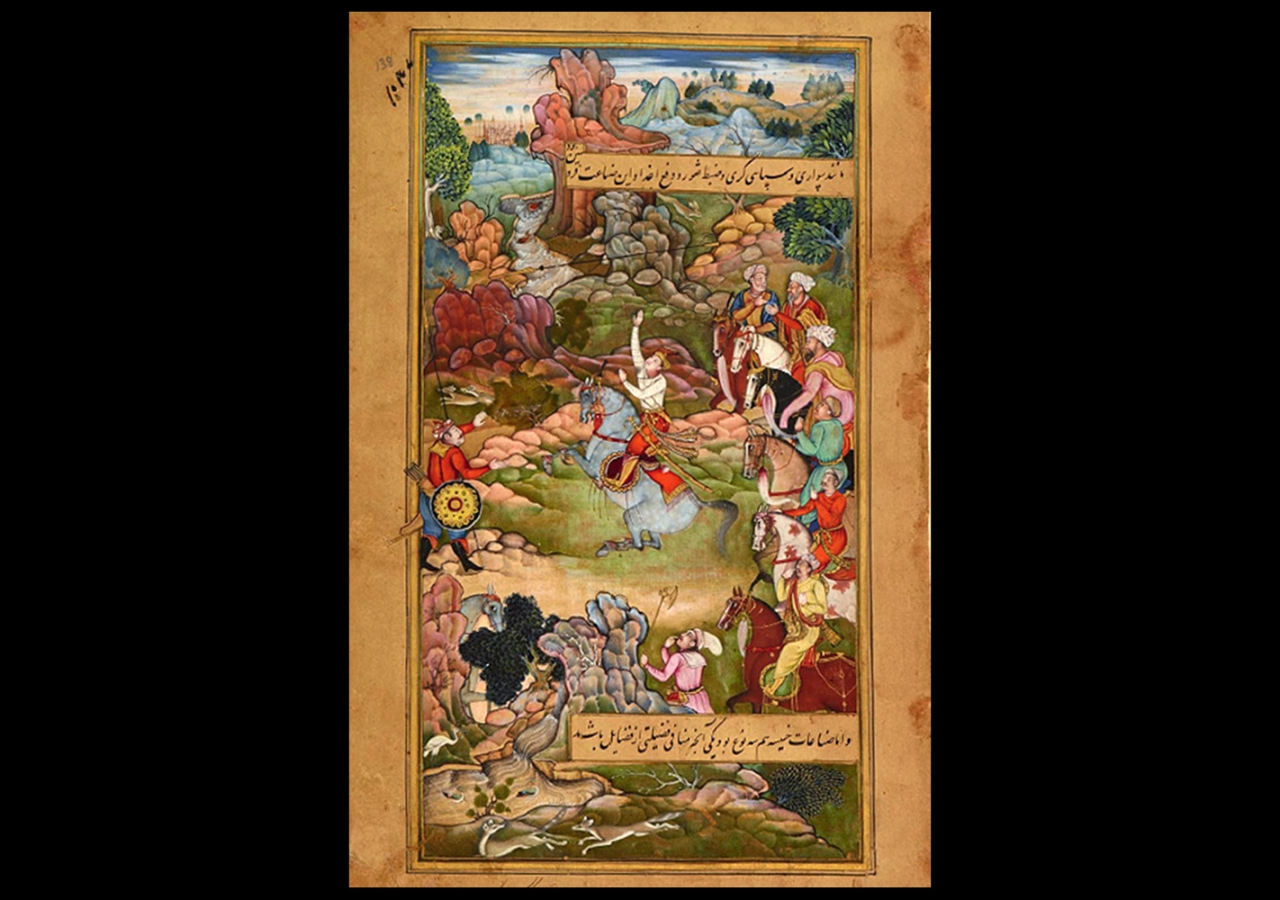

For Ismaili Muslims, the sweep of history offers lessons. From the Arabian peninsula to North Africa, from Persia to Central Asia, from the Indian subcontinent to Africa, Europe and North America — as the Jamat as spread, the centuries have been marked with challenges and opportunities, with accomplishments and setbacks.

In all times and in all places, the Jamat has looked to the Imam of the Time, who has protected and guided the community in spiritual and worldly matters. And throughout the succession of 49 hereditary Imams spanning 1 400 years of history, the Jamat has been continuously reminded of the value system that anchors our faith, uniting us in our identity, and which continues to serve us as it has served our ancestors.

The notion of intellect as a facet of faith sits at the heart of our values. Foundational to the Shia tradition of Islam, it is attributed to Hazrat Ali, who taught that the use of one’s intellect is the correct behaviour at any given time. Hazrat Ali tied intellectual reasoning to aspects of life, from social justice to guiding individual behaviour, as well as its role in the practice of faith and in the service of others.

The Ismaili intellectual tradition runs like a thread throughout our history. From the foundational teachings of Hazrat Imam Jafar as-Sadiq, to the Rasail of the Ikhwan al-Safa. From the establishment of Dar al-Ilm and al-Azhar as seats of learning a thousand years ago, to the intellectual legacy that the Fatimids bequeathed to civilisations that followed. From the libraries of the Ismaili castle-fortresses dotting the Alamut valley and the Jabal Bahra, to the creation of the first Aga Khan Schools in Africa and Asia at the turn of the last century. Today, that same intellectual thread extends through the Aga Khan University, the University of Central Asia and the Aga Khan Academies established by Mawlana Hazar Imam.

“The single most important element in securing an individual’s future in fragile or unstable contexts is education,” says Dr Mahmoud Eboo, Chairman of the Ismaili Leaders International Forum. “For 60 years, Mawlana Hazar Imam has pushed us along the education curve — from basic education to meritocratic higher education, to lifelong learning, to beginning that education process in infancy. An educated person can survive and flourish in any new context.”

Education is a building block leading to financial stability and wealth creation. With this comes the opportunity to be generous with one’s wealth, and to contribute time and talent for the betterment of society.

“One of the energising forces that makes a quality civil society possible,” said Mawlana Hazar Imam in his 2014 address at Brown University, “is the readiness of its citizens to contribute their talents and energies to the social good. What is required is a profound spirit of voluntary service, a principle cherished in Shia Ismaili culture.”

During the Golden Jubilee, the tradition of nazrana was extended from an offering of material wealth, to include gifts of time and knowledge. Combining ethics of generosity, volunteerism, and the sharing of knowledge, the nazrana is an opportunity for individual members of the Jamat to work with Jamati and Imamat institutions in the service of humanity.

“The Jamat’s success in settling in new contexts is their ability to embrace new traditions without giving up their own, and to contribute to the societies in which they have chosen to settle,” explains Dr Eboo.

The values to which we adhere are not unique to the Ismaili Muslim tradition, nor are they exclusive to Islam. Rather, they are common across many faiths, and have stood the test of time.

Religion is rooted in the Latin word ligare, meaning “to bind,” as it provides a way to hold a community together and provide a common identity. The importance of religion and a sense of the sacred was underscored by Mawlana Hazar Imam in his 2006 address at the University of Évora, when he warned that societies that exercise freedom from religion “will find themselves lost in a bleak and unpromising landscape — with no compass, no roadmap and no sense of ultimate direction.”

The guidance of our Imams and the timeless ethics and values that we uphold throughout our lives, are the compass that has given the Jamat its sense of direction over centuries. Today, at the cusp of Mawlana Hazar Imam’s Diamond Jubilee, the Ismaili community is well positioned to contend with the challenges of our time.

Working together, in the Ismaili spirit of kindness, generosity, and thoughtful reflection, we can shape new opportunities that will benefit future generations in the centuries to come.

This article is part of a series published in the lead-up to Mawlana Hazar Imam’s Diamond Jubilee.